Maintenance Work: An Interview with HOME-OFFICE

Contributors

Out of Work // Out of Control

Daniel Jacobs (YSoA, 2014) and Brittany Utting (YSoA, 2014) are co-founders of their design collaborative, HOME–OFFICE (https://www.home-office.co/). Daniel Jacobs teaches at Taubman College of Architecture + Urban Planning at the University of Michigan. Brittany Utting teaches at the Rice School of Architecture and previously taught at the University of Michigan where she was the 2017-2018 Willard A. Oberdick Fellow. On Thursday, April 9th we Zoomed with Daniel and Brittany to discuss their recent work and their concept of a labor-form in architecture.

Andrew Economos Miller (AEM): In your recent article “UN-WORKING,” you lay out the idea of a general labor-form of architecture. How does that labor-form inform your work and how we might think about our own labor as architects?

Daniel Jacobs (DJ): We’ve been imagining this idea of labor-form pretty extensively. It’s not just the production of the architectural document, but it spans a much broader and more fundamental set of conditions, all the way back to the resource extraction of material. That’s where the RE–TAGGING project started from. There’s this whole supply chain of different moments where labor takes place along the production of architectural objects. As architects, we often have no sense of what quantities of embodied labor or what labor footprints are implicated in those elements. The original ambition was to track these issues, going all the way back to the inception of a built piece of architecture.

Brittany Utting (BU): There’s also an idea about making visible the material, social, technological, and industrial histories that are sedimented over time onto objects, affecting their form and changing the way we appropriate, extract, and use material. Labor-form is about looking at how the built world is not a product of the will of the architect, but actually results more from a flux of ideas, of histories, of personal stories, and of displays of power and generosity. It’s about the generosity of the architect to step back and not think that we’re the only shapers of the world, but that we’re one player, one lesser player in a much larger material history. That’s the conceptual background, but it also affects the way we design, not just the way we see the world, but the way that we act on it. A lot of our practice is about setting the terms of what labor-form can be, what its capacity is. It’s also about mobilizing data, documentation, details, the stuff of architecture, and the stuff of production. We use those to start changing tectonics, changing material assemblies, and changing the way that we understand form. In our work, we try to always push the tectonic detail, push the reveal, push the way that a few pieces of material come together and use that as a way to start indexing how labor has shaped architecture.

DJ: In the work that we’ve been starting to do, one of the ways that we’re trying to assess and step back from more normalized modes of production—from clicking in Rhino to organizing our work with other people who are working on projects with us—is a very careful tabulation of the hours and the specific qualities of the work that we’re doing, and trying to manifest exactly how that work happens and then display that as part of the project. Making visible that bare labor production is almost the most important part of the project because otherwise it’s just a black box where you go to an exhibition and you see the three names that helped, but no one actually knows what went into it, how much it cost, all of that stuff. I think that’s critical as well.

BU: Exactly. Where’s the timesheet? What’s the budget? Were there overages? Who funded it? How was that funding procured? How was it distributed in terms of material use, but also in terms of labor? How do we understand students as workers? How do we understand ourselves as unpaid architectural workers that are producing a creative product? Why don’t we bill for our work? It’s about using not only the details but also mobilizing the Google Sheet and the Google Drive as a way to bring to light these untold histories, untold micro-histories and micro-economies that exist in every architectural transaction.

DJ: I’m involved in the Architecture Lobby chapter at the University of Michigan and one of the ways this has come up is that in the academies a lot of students work for faculty on their projects and exhibitions, but a lot of them didn’t have contracts with the faculty members. They make word of mouth agreements like, “I’ll pay you this much hourly to do this.” In this way, a lot of students can’t negotiate these agreements or hold faculty accountable in cases of excessive work. After the Midwest Convergence (an event held in the Spring of 2019) the students came together to produce a document for working for faculty for students at any school to share with their faculty. It’s not a binding legal contract, but at least it’s an agreement in writing

AEM: Yeah, I think this is a good point to just jump right into RE–TAGGING (www.home-office.co/re-tagging), how does that project make labor-form apparent?

BU: Part of the project is looking at contemporary critical fashion practices that are reappropriating the label, making visible the relationship between use-value and exchange-value. For example, a shoe has value not because it’s a great fit and you can run really fast with it, but because of how it participates in that branded enclosure. We were interested in that fashion apparatus, that labeling apparatus, and how we can détourn this relationship between use-value and exchange-value, using it as a way to rethink one of the documents that is embedded in architectural practice: the finish schedule. There’s something about the quickness of the label: it’s cheap, it’s accessible. The tags that we produced reference a continuously updating online data sheet. They’re a relabeling of architecture, not just by its authorial provenance, but by its material provenance. How do you lay bare the actual material assemblies? The way that we choose and define materials in architecture is that moment in which we put into motion a vast chain of material resources, environmental economies, and labor networks (despite the finished building looking so static). But in fact, the building is just in pause in this heaving logistical network. The quick ready-made label is a way to start indexing these larger ecosystems at play.

DJ: The reality of the physical makeup of the built environment is that once it is in play and physicalized, there’s no going back, there’s no undoing it, no un-working it. The key is that the labeling system is a nonproprietary set of labels. It’s not the serial code on the window that allows the corporation that produced it to understand which batch it came from. It’s for a different constituency entirely to be able to say like, “oh, this is this material.” Obviously, we’re being cheeky when we say it’s just “MT–01.” It would actually be a much more complicated set of parameters and labels that would allow you to retrace that lineage through all of the heaving logistics.

BU: It’s important to understand the violences of proprietary knowledge as it relates to architectural data. This data is often only accessible to a privileged few in a profession. It is often completely illegible to people who maybe haven’t been exposed to the standards of architectural practice. And so the moment that data, that information, that technology is enclosed by a corporation or by an institution of measurement, it makes that knowledge private and inaccessible. This data sheet that we have is free and open to the public. The more important act than the labeling is the accessibility of it. How do we make this architectural data set open-source?

DJ: Additionally, its deployment becomes a visual nuisance on architecture, like graffiti. It’s bright yellow and large, something that is unavoidable to the eye. We’re interested in that lingering and latent annoyance of the visual field where all the sudden you have to encounter the data set.

DD: I had a question about deployment because the tags do bring this participatory aspect to the work that reflects the collective knowledge in the spreadsheet. It seems like the spreadsheet is ripe for different modes of deployment. Do you see other modes of deploying that information or other ways of creating different publics around the spreadsheet?

BU: Yes! Worker groups all over the world (such as New York’s museum workers) have organized and shared a spreadsheet through which they are radically transparent about their wages, about their salaries, and about the expectations of their weekly workload. That radical transparency has given many workers that feel isolated or precarious the leverage they need to organize, to mobilize, to ask for greater worker protection, better salaries and more compensation for overtime work. Beyond worker movements, how can we make data sets that have equal agency in architecture? I can imagine that there are multiple ways that these sheets can be deployed. Obviously, there could be one of architects making visible their own wages, their own work experiences. But I think this idea of giving material a voice through the finish schedule is about allowing other agents in architecture to come forward and make visible their own histories and economies.

DJ: The other thing to note is that the tools and technologies that we have available to us are that simple, like the Google Spreadsheet, or the shared drive. We spoke to the woman that started the museum workers spreadsheet in New York. She was in a cab going home and just made the spreadsheet. And in about a week, thousands of entries came in and they started a union. The informational infrastructure is dumb and cheap to a certain degree, but it can get incredibly thick very quickly and layered onto that simple document.

BU: In architecture, we talk about softwares and BIM models and those professional tools that are fundamentally shaping the practice. However, there are other digital interfaces and data sets at play that can be used to give more voice and agency to precarious people or to precarious ecosystems, ecologies, economies, rather than only being used to produce and perform architecture. When we talk about the way that the digital has radically shaped the collective practices of architecture, I think it can’t just be through the interface of the proprietary software model, it has to be through the grassroots open-source commons that we all have access to.

AEM: To switch it up a little bit and talk about MODEL–HOMES, how does that project begin to confront the social-labor structures embedded in the home itself?

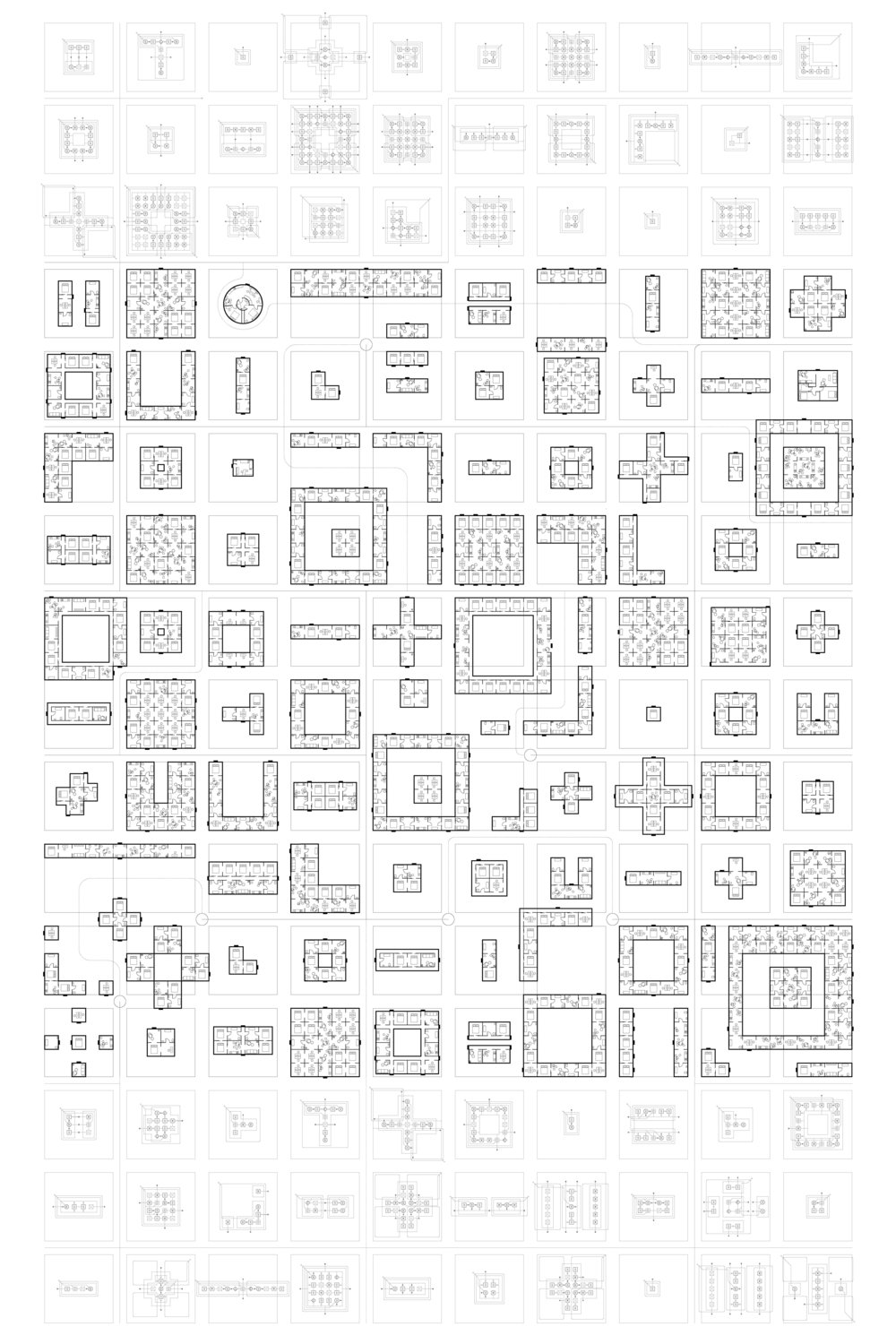

BU: For MODEL–HOMES, labor was a part of the project in so far as understanding how the reformatting of domestic programs can overturn the institutionalization of gendered forms of work and care. The process of design was about playing through the combinatorics of domestic programmatic changes in the home that would in turn produce new kinship structures, resituate cooperative production, and support more varied formats of intimacy and collective life. But the project also interrogated the modes through which we consume the home itself. The project was about unpacking the developer’s catalog and its associated architectures: the showroom and the vitrine. It was important for us to look at how we could make visible the model home as a spatial product, an object consumed and presented to a set of customers. We were also interested in how the model home was consumed in a sense by a developer, studying how it was deployed as a territorial, planometric attack on the suburban landscape. We were interested in the almost militaristic capacity for suburban development that essentially deploys a matrix of houses that each prescribe a specific way of producing, reproducing, and consuming. As you multiply these domestic practices to the scale of the suburb, it has a profound social and ecological effect on how we live together, how we work together, and how we consume space and material products together. By provoking a re-collectivization of the suburb—reversing the redundancies, the privatizations, and the individuations of suburbia—we could discover new social formats. Part of the communal capacity of the home is in this sharing and reprogramming of domestic work.

DJ: We like to adhere each project to an underlying document, whether a finish schedule or the developer catalog of homes, in order to ground the architecture in a set of material relationships, labor structures, or consumer structures. What’s interesting about the developer catalogs specifically is that the combinatorics that are usually deployed in the suburban landscape are a labor-saving device for the contractor: it essentially transforms the home into a ready-made.

BU: Like the Levittown assembly line.

DJ: The developer catalog is essentially a series of self-similar interiors re-clad with differently stylized exteriors with only minor spatial adjustments and decisions. The idea behind MODEL–HOMES was that you’re still deploying the same combinatorial tactics that the developer uses, but you’re also embedding a much broader and more varied of social associations within that floor plan, one that is much more diverse than the typical suburban home. We wanted to produce a new developer’s catalog that introduced a different set of relationships through a sleight-of-hand.

DD: Was there a set of criteria you had one eye on to make sure that these combinations yielded something that was subversive to the typical developer home and yielded something more productive toward common goals?

BU: The project was looking at the balance between pursuing typological forms “most varied and beautiful”—like the end of The Origin of Species—and a set of experiments that tested what happens when you concatenate a series of bedrooms, not separated by hallways, but as an enfilade suite. All of a sudden, that shared bedroom becomes an extended collective bedroom, a communal space for the practices of reproduction and other forms of social intimacy. All of a sudden, the architecture opens up a space for a new type of subject, a new way of performing the self, and a new way of performing intimacy. We were interested in testing out all these different combinatorial games to see how new social structures would undo f traditional kinship associations. We wanted to play out those combinatorial games to see what monsters would result..

DJ: Also embedded within all of the typological variants was a challenge to traditional lot lines, property separations, and density. When the combinatorial game was deployed fully, it made a higher density neighborhood with challenges to every property division.

BU: Yes, it happened on two scales. One scale is the concatenation of domestic programs, but the other was through its deployment at the scale of the suburban neighborhood. The project proposed a restructuring of private property itself, a new practice of commoning in which property, subdivisions, and territorial allotments were put into question by the occupation of property lines by different models. The project wasn’t just an autonomous game of typology. There was an autopoietic capacity within the system to reinscribe new social formats within the suburbs.

DD: I really like imagining what these plans look like executed with the same aesthetic finishes of like a McMansion home.

AEM: Were they planned to be clad in the same way as the developer catalog?

BU: That’s a good question. The project is largely agnostic to cladding because it was about stripping the home bare of the aesthetic ideologies that are often at play in the developer catalog, removing the stylistic variations that mask the disciplining ideologies inscribed in the plan. The plan is what produces a way of life. It’s the plan that produces a type of subjectivity. So there was no cladding. It was purely a cybernetic game, a game that only re-organized and re-alloted space.

DJ: As soon as you pin that down or say that it’s a diverse spectrum of styles and variants, then all of a sudden, that becomes the critical frame. So I think it’s important that the homes don’t have that aesthetic expression.

AEM: Over the past few years, you had a series of workshops at the University of Michigan about labor, called UN–WORKING. How have those informed your recent projects?

DJ: The conversations we had at those events seeded a lot of the subsequent pedagogical explorations, conversations, and projects that we’ve done.

BU: They were about using the workshop format because it’s fast and collective. The workshop aligns technical production with communal action. The workshops wanted to create a new ecosystem in the school that encouraged all of us (students and faculty alike) to more critically engage in the project of labor. The workshops questioned the hyper-production of space, of form, and of image in the architectural academy. We wanted to create a platform for agonistic debate about these issues. It’s so easy in architecture school to just hone in on your own myopic project, but it weakens our capacity to get together and talk about our shared status as workers, as architectural producers. The project wasn’t about not working. It was about un-working architectural production and un-working architectural work.

DJ: One of the things that’s held my attention is the difficulty of maintenance and continuation of discourse around issues of labor. How often do you need to continue to gather together and collectively discuss these issues so that they don’t fade? A lot of workshops right now are basically intense zones of production, made up of all-nighters and charrettes. We were interested in the idea of the workshop as a space for discourse instead of production, reading debates instead of charrettes. But with the constant turnover of graduating students every year, we almost have to restage these conversations every year so that the ideas can persist. And then architectural pedagogy, and expectations of production, slowly change over time because of this maintenance and the care of the discourse itself.

DD: I like the idea of the workshop as a pressure release valve for architectural education.

DD Were there particularly promising results from the UN–WORKING workshops that you think can carry into architecture pedagogy or curricula more generally or broadly?

DJ: The workshops did produce conversations throughout the school, such that many students I spoke with tried to reframe their projects and processes through issues of labor. Even if that happens for a month, it has a huge impact on the way that the school works. Again, it’s just about constantly repeating that work, maintaining the conversation.

BU: It’s not about an end result. But I think that’s the power of it. A result is often something that occurs out of a set of unequal transactions or exchanges in value. We wanted to question the idea of a result or something that you can point at in architecture school. The UN-WORKING workshops were most critically about the maintenance of labor discourse; the conversation was held in the minds of those who participated in the work. Their labor was being a participant performing in that workshop. It’s really important for there to be space in architecture not to have to produce an end result for evaluation.

BU: A critical architecture practice is one that’s both in the world, but also far enough away that you can critically examine how architecture participates in these processes of production. That distance, the space that you produce between the actual work and its critical capacity—that space between production and contemplation—is essential in architecture. The UN-WORKING project was sometimes productive and sometimes unproductive… and that’s okay!