The gateway to conflict: Postmodern necromancy in Copenhagen

Contributor

Sequels:Afterlife

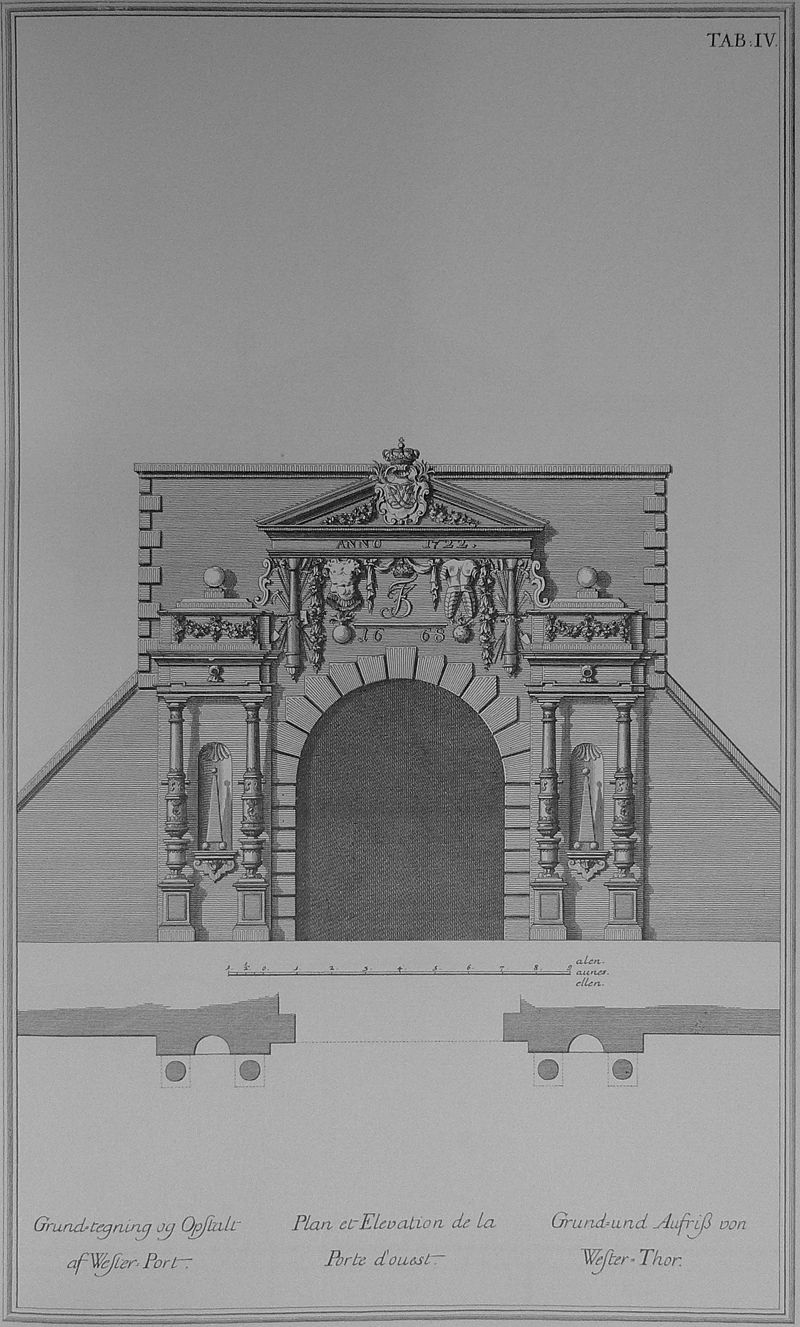

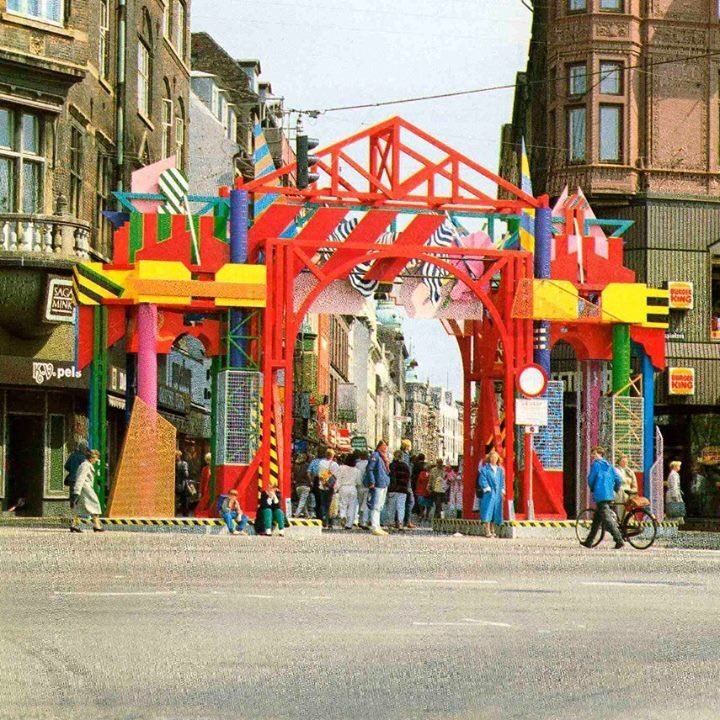

In 1986 the Danish Postmodern architect and writer Ernst Lohse completed his first major work, a temporary gate leading to Copenhagen’s Strøget, the longest pedestrian-only shopping street in the world. The original review of the gate in the May 7, 1986 issue of Kristeligt Dagblad, titled “And so Copenhagen Got a Gate Again” cast Lohse as a kind of architectural necromancer, a re-animator of long-dead historical structures: “The last time Copenhagen had a gate at this entrance was under the initiative of Frederik III, but that has fallen to the teeth of time and can today only be seen in The Danish Vitruvius.”[1] It was Lohse’s explicit intention to revive Vesterport, the original western gate to Copenhagen, as his designs sought to enact his 1986 manifesto Our Construction Must be Based in the Irrational which argued that Danish architects must work to “rediscover the entirety of our formidable cultural heritage” through the Postmodern articulation of historical forms.[2] The first Vesterport was built in 1558 and underwent significant renovations in 1668 under Frederik III as part of the larger 17th century process of fortifying Copenhagen, becoming its own kind of architectural novelty in the process. Frederik III’s gate flirted with Postmodern sensibilities some 300 years early with details like the use of cannon barrels as columns supporting the main cornice. These original cannon barrel columns were later removed during the 1772 renovation by Frederik IV, and Vesterport was eventually destroyed in 1857 when Copenhagen ceased to be a fortified city.

Lohse’s own design references the multiple iterations of the original gate in a negotiation between historic fidelity and colorful Postmodern aesthetics; the result is a vibrant husk of architectural history, deconstructed and symbolically potent. Yet the context surrounding Lohse’s gate was quite different from that of 17th century Copenhagen. Where the original gate had a guardhouse/customs checkpoint to its left and a market for selling hay and horses on its right, Lohse’s structure was flanked by a luxury furs tailor and a Burger King. These adjacencies betray the larger aims of the project, which was funded by the city of Copenhagen to increase tourism and promote the shopping district. Lohse originally planned to (re)build not just one entrance to Strøget but three, reviving the other gates Østerport and Nørreport so that the 17th century fortifications might be reborn together as instruments of commercial spectacle, branding neighborhoods through an early example of the “pop up” format. We might question the decision to use the typology of the gate, which has historically been a marker of exclusion and military might, towards these ends.

Indeed, the structure was controversial; despite Lohse’s own self-professed quasi-nationalist affinity for Scandinavian history and architectural symbolism, many claimed that the gate was not Scandinavian enough. This sentiment was echoed in other critiques of Postmodern architecture in Scandinavia, a result of the movement designing avant-garde reinterpretations of historical structures rather than earnest reproductions—a different kind of afterlife.[3] However, once the temporary structure approached the date of its scheduled demise, the focus of discussions about the gate changed, becoming “no longer about art, but about politics”; a follow-up article in the July 17, 1986 issue of Kristeligt Dagblad read, “The gateway to Strøget has become the gateway to conflict” as opposing political and social groups fought over its demolition or preservation. The project lived up to its characterization as a “gateway to conflict,” as diverging public attitudes around politics, national identity, and preservation were played out through discussions of this curious architectural object. This is in line with the larger discourse around Postmodern architecture in Scandinavia, which became a site where “emancipatory movements like feminists, environmentalists and radical leftwing movements, overlapped (unintentionally) with conservative forces struggling towards a more liberal society.”[5] In a reversal of typical conservative attitudes towards public arts funding in countries like the United States, it was members of one of Denmark’s more conservative political parties that campaigned for state funding to permanently preserve this public art piece, writing, “It is pathetic and contemptuous for historical art like ‘the Gateway’ not to be preserved for the future.”[6] In the end, the gate was destroyed, an ironic confirmation of Lohse’s own claim that “Culture lives where conformity is burned down.”[7] It is significant that this project, an early built example of Scandinavian Postmodernism, became such a site of conflict after the movement’s initial incubation in academic publications and exhibitions; the revivified gate became a lightning rod, with discourse leaping from the page to the street.

The spirit of Lohse’s project is inherited by contemporary reanimations of European classical architecture through Postmodern aesthetic tactics, such as Yugoslavian government buildings being covered with vinyl stickers of faux traditional ornament in what Marco Icev has called a “plan for the destruction of Modern monuments through Postmodernism.”[8] Given the current context of right-wing European nationalism’s obsession with classical architecture, reactionary critiques of Denmark’s immigration policies, and the gate typology’s own symbolic power and exclusionary origins, it seems possible that Lohse’s sequel to Copenhagen’s original gate might get a more sinister follow-up, rounding out the saga of Vesterport into a trilogy.

[1] All of the original Danish texts were translated into English by Henry Weikel, a Mst. Candidate in English Literature at the University of Oxford. “And so Copenhagen Got a Gate Again.” Kristeligt Dagblad, May 7, 1986.

[2] Lohse, Ernst. “Our Construction Must Be Based in the Irrational.” Kristeligt Dagblad, July 26, 1986.

[3] See Mats Tormod, “Venturi in Manhattan”, Arkitektur, No , pp. 30-31 1980

[4] “Gate to Conflict.” Kristeligt Dagblad, July 17, 1986.

[5] Mattsson, Helena. “Revisiting Swedish Postmodernism: Gendered Architecture and Other Stories.” Konsthistorisk Tidskrift/Journal of Art History 85, no. 1 (2016).

[6] “Gate to Conflict.” Kristeligt Dagblad, July 17, 1986.

[7] Lohse, Ernst. “Our Construction Must Be Based in the Irrational.” Kristeligt Dagblad, July 26, 1986.

[8] Icev, Marco. “The Archive Is Burning.” UCLA Urban Humanities Salon Exhibition and Symposium, June 2019, 46.

Lauritz de Thurah, Elevation of Vesterport the Western Gate of Copenhagen: Built in 1668 by Frederik III and renovated in 1722 by Frederik IV, etching, from Den Danske Vitruvius (Copenhagen, 1745).

Ernst Lohse. The Western Gate of Copenhagen, photograph (1985).