3 Days, 3 Publics: The State of the Art of Architecture at the Chicago Biennial.

Contributors

Publics & Their Problems

DANIEL GLICK-UNTERMAN (M.Arch 17′) and MISHA SEMENOV (M.Arch 18′)

“You fuck this up and you’ll set Chicago architecture back for years.”

-Stanley Tigerman (M.Arch ‘61) to Sarah Herda, co-director of the 2015 Chicago Architecture Biennial

This weekend, correspondents Daniel Glick-Unterman and Misha Semenov traveled to Chicago to represent P A P R I K A at the opening preview weekend of the Architecture Biennial, an enormous event that brought more than a hundred architecture firms together around the loosely-defined topic “The State of the Art of Architecture,” a theme borrowed from a conference organized in Chicago by Stanley Tigerman (M. Arch ‘61) almost forty years ago, in 1977. That event, funded by the Graham Foundation, was fairly hermetic, small, and elitist. Its 2015 counterpart aims to be something different. As Sarah Herda, the co-artistic director of this year’s event, and current Director of the Graham Foundation, said in a March 23rd interview with New City, “It’s about making ideas public, and giving the public access to ideas.” Indeed, this event is explicitly marketed as being for the public: admission is free; its main venue, the Chicago Cultural Center, is centrally located and has a longstanding relationship with the public, as such; and the exhibition itself is well-complemented by a variety of partner programs, talks, and exhibits at more than 20 other venues throughout the Windy City.

Given the theme of this week’s broadsheet, ‘Publics and Their Problems’, and considering the gravity of an event like the Chicago biennial, we set out to explore ideas about what, and who, comprises the public addressed by this biennial and, furthermore, how the biennial frames its relationship to that public. Herda alludes to this in her description of the biennial’s overarching mission: “It’s not only leaders of institutions or political figures, but everyone in daily life making decisions about space. We want the Biennial to be a resource [for] the public, a way to think about … things in a new way.” Joseph Grima, the other co-director, echoed Herda’s words in an interview with P A P R I K A: “…the biennial is making a case to the public about the value of architecture,” he explained. Given that the biennial has been heavily promoted by both Chicago mayor, Rahm Emanuel, and the event’s ‘presenting sponsor,’ BP, we feel it important to analyze the organizers’ view of themselves in relation to the public; to consider whether or not events like this one might serve to construct new notions of the public; and to ask of the people “making decisions about space,” those to whom architecture will make its “case”, who they really are.

Here, we present what we found to be three distinct publics, observed on each of the biennial’s three opening days, along with a series of anecdotes which, in sum, begin to tease out what, exactly, this notion of “the public” means.

MIT self assembly lab

Day 1: The Press

The first day of the Biennial catered to assembled members of the press and local politicians, who gathered to witness an opening endorsement by mayor Emanuel, followed by the first panel of the weekend, “WHAT IS URGENT: 99 Telegraphic Manifestos.” Sitting in awkward and blocky, well designed if proudly playful rocking chairs, the directors, along with Serpentine Gallery curator Hans-Ulrich Obrist, invited the event’s participants to take the stage, announcing each one in a manner not unlike that of a game-show host (“Ladies and gentlemen, please welcome ____ to the stage!”). Each was then asked to present a fifteen-second manifesto addressing “what is urgent in architecture today.” With manifestos recited, and generic follow-up questions answered, the participants were escorted out to a brisk round of applause, as Herda and Olbrist announced the precise location of their exhibits, and called the next participants to the stage.

Could the organizers have developed a format more explicitly focused on each firm, or on the details of their exhibits? Certainly. But its “telegraphic” nature was part of the point. Per Grima: “We wanted the participants to embrace the space of 15 seconds. That length has a meaning and a rationale… it is, like the exhibit itself, telegraphic… Architects have to be telegraphic today. In our reality, in the extreme competition for attention, architects have to be able to pick their language.” Several manifestos were quickly re-posted to Instagram, Twitter and Facebook, so perhaps Grima has a point. Even if realistic, the idea that architects should be able to communicate to the public in the span of 15 seconds, through the media, represents a fundamentally novel approach to the presentation of architecture.

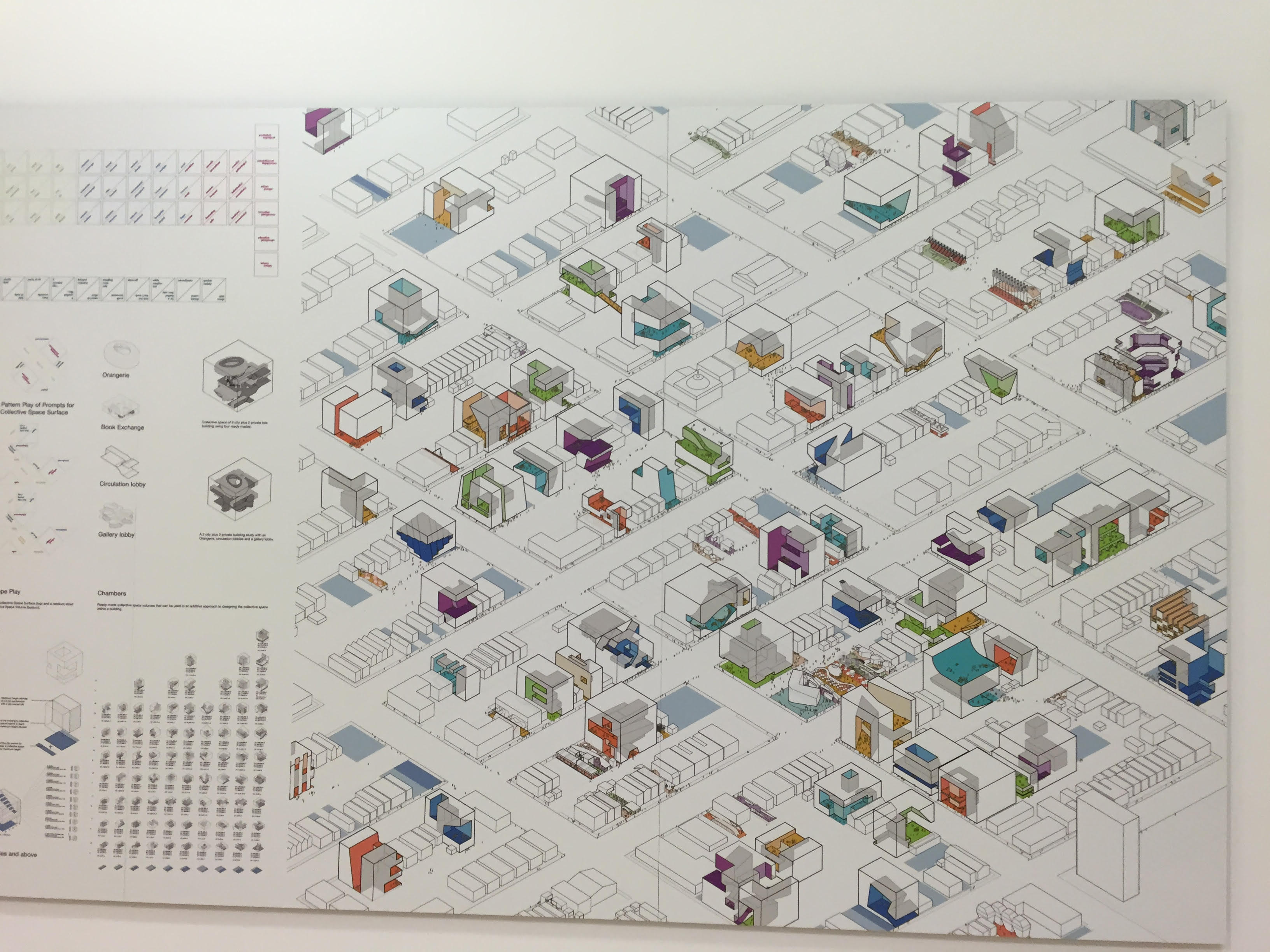

Available city

Day 2: The Profession

On the second day, the halls of the Chicago Cultural Center bustled with activity, as exhibiting architects, local designers, collaborators, workers from other disciplines, and a veritable army of design critics, writers and plus-1’s poured in to attend VIP-only events. Lectures and openings were held throughout the city at various off-site venues, after which the participants gradually converged upon the main attraction. The day culminated with a euphoric reception at the Cultural Center, featuring an open bar, two dance floors, several DJs pumping deep-house and soul music, and hors-d’oeuvre tables serving hot pretzels with a cornucopia of dipping sauces arrayed against BP logos.

Not all the architects, however, were drinking the Kool-Aid. Earlier that day, at the “Unprogrammed Architecture” roundtable, a discussion about planning for the unexpected in architecture and urbanism spiraled into a litany of accusations against the event, foremost among them a charge that two days of exclusive-access openings had forced a shutdown of the Cultural Center’s regular public services, resulting in a scene of homeless Chicagoans, accustomed to showering at the Center’s facilities, being denied access to the building, while a very different “public” sipped red wine and vodka-cranberry inside. This conversation was cut short by the Cultural Center’s program director, who praised the public nature of the event.

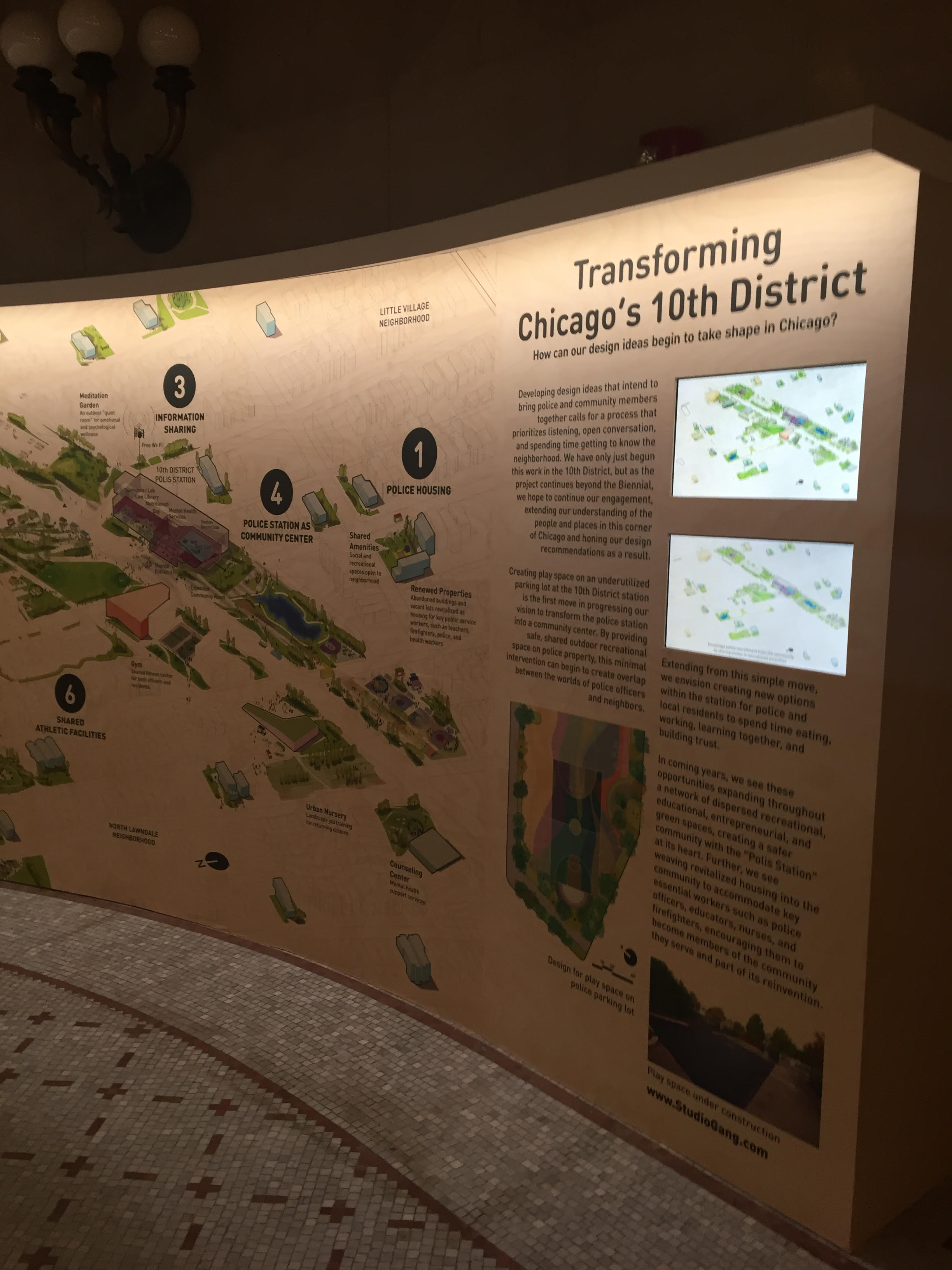

Polis station

Day 3: The Chicagoans

Saturday marked the official opening day of the exhibition to the general public. At last, the press, the designers, the writers, and the city politicians made way for a much more diverse group of visitors. And finally, the exhibits could fulfill the task Grima had bestowed upon them: “speaking about architecture in extremely direct, simple terms is subversive in a situation in which architecture tends to be discussed in extremely technical terms, in esoteric terms, in terms that transcend the direct experience of the public.” On Saturday afternoon, the halls were filled with Chicagoans broadcasting cell phone photos (including selfies in great profusion), families with kids, elders explaining what plans, sections, and models were, and a residue participating architects, commenting to each other about how much the exhibits had “come alive” with the arrival of visitors.

While the array of well-executed 3D-printed models and colorful computer drawings presented here exemplify the sort of tried-and-true representational methods familiar to architects and designers of every stripe, for this visitor, they still made a strong aesthetic case for the value of architecture to “the public,” framing large-scale concerns like climate mitigation and urban redevelopment in new, aesthetically accessible terms, thus emphasizing the power of architecture to articulate the aspirations, and to help solve the problems, otherwise thought to be the province of other disciplines. Ultimately, it was an optimistic framework, a promise to the public that architects can, and should, participate in the development of solutions to the world’s most pressing issues. Will Herda and Grima’s “subversion” be effective? Can their claim to subversion be taken seriously, considering the role of BP and other private interests in presenting the event? As Stanley Tigerman put it, “Joe [Grima] and Sarah [Herda] — their reputations are on the line. That pressure on them is actually useful in terms of warding off corporate greed. If they fuck it up, so be it.”