Rejas, Death and Ornament

Contributor

Figments

This brief essay is the result of a series of visits to the Santiago General Cemetery, motivated by an obsession that until now has been titled ‘Rejas: Objetos de mediación’ (Fences: Objects of mediation), an ongoing creation and research project, within the framework of the Master’s program in Architecture at the Universidad de Chile.

The fence —’reja’ in Spanish— is usually understood as a defensive object, or as a limit that indicates property. However, this architectural element also has the potential to achieve greater complexity than the typical distinction between inside and outside. In contrast to the categorical boundary of a wall, the fence is more of an ambiguous screen that, while separating, allows one to see.

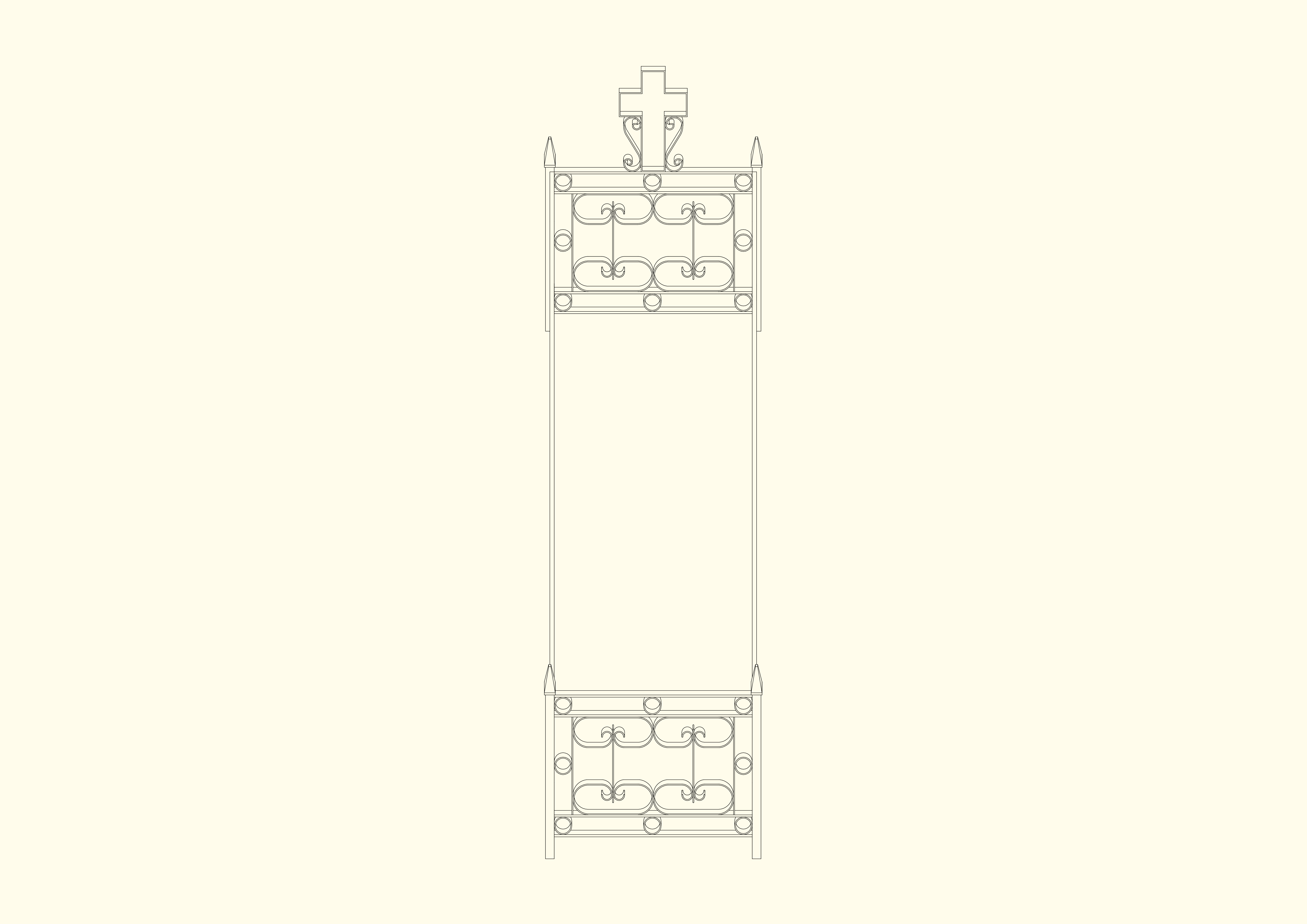

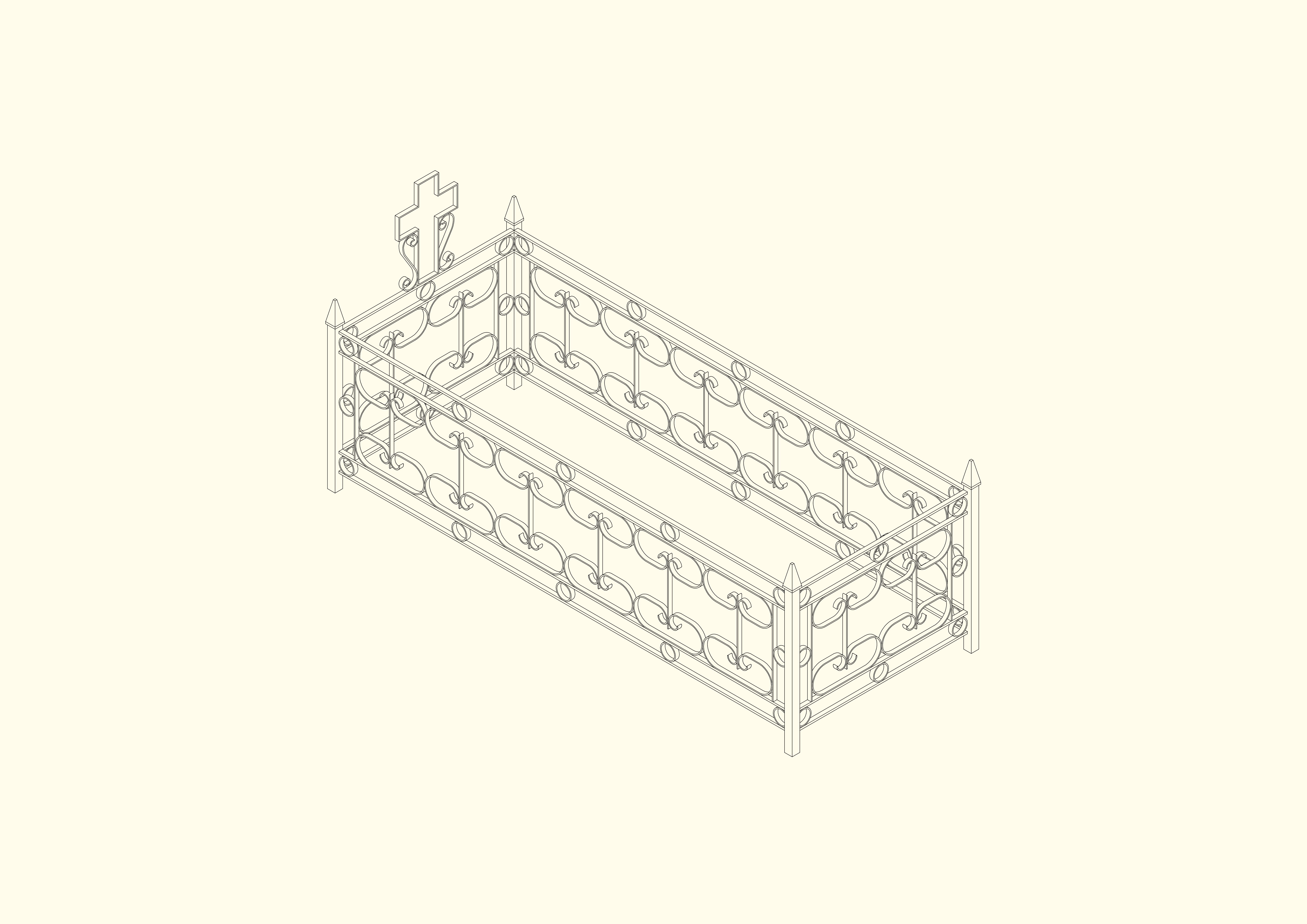

The fence is loaded with symbolism through different types of ornamentation that define its design from a remote past, linked to Catholic cathedrals in Latin America, where ‘rejería’ structures were complemented with ‘cresterías’ and ‘montantes’, ornamental elements related to religious principles. For instance, in Santiago de Chile, the design of fences in religious buildings was inherited by the cemeteries and at first regulated by the Church itself.

Over time, mausoleums and graves began to include increasingly complex designs to their structures that included different styles, such as Baroque and Jugendstil, usually belatedly. This diversity of styles is still observable in the old section of Santiago General Cemetery. The fence also became more elaborate as the scale of its application varied, for instance, when the mausoleum loses presence and the gravesite appears with notable frequency. Is in this context where the fence achieves greater autonomy, becoming a perimeter boundary safeguarding the grave. Likewise, the urban pericenter and periphery of Santiago, it is possible to conceive the presence of a typology that establishes an ambiguous relationship with the surrounding landscape, allowing the growth of vegetation and the observation of the interior of the perimeter.

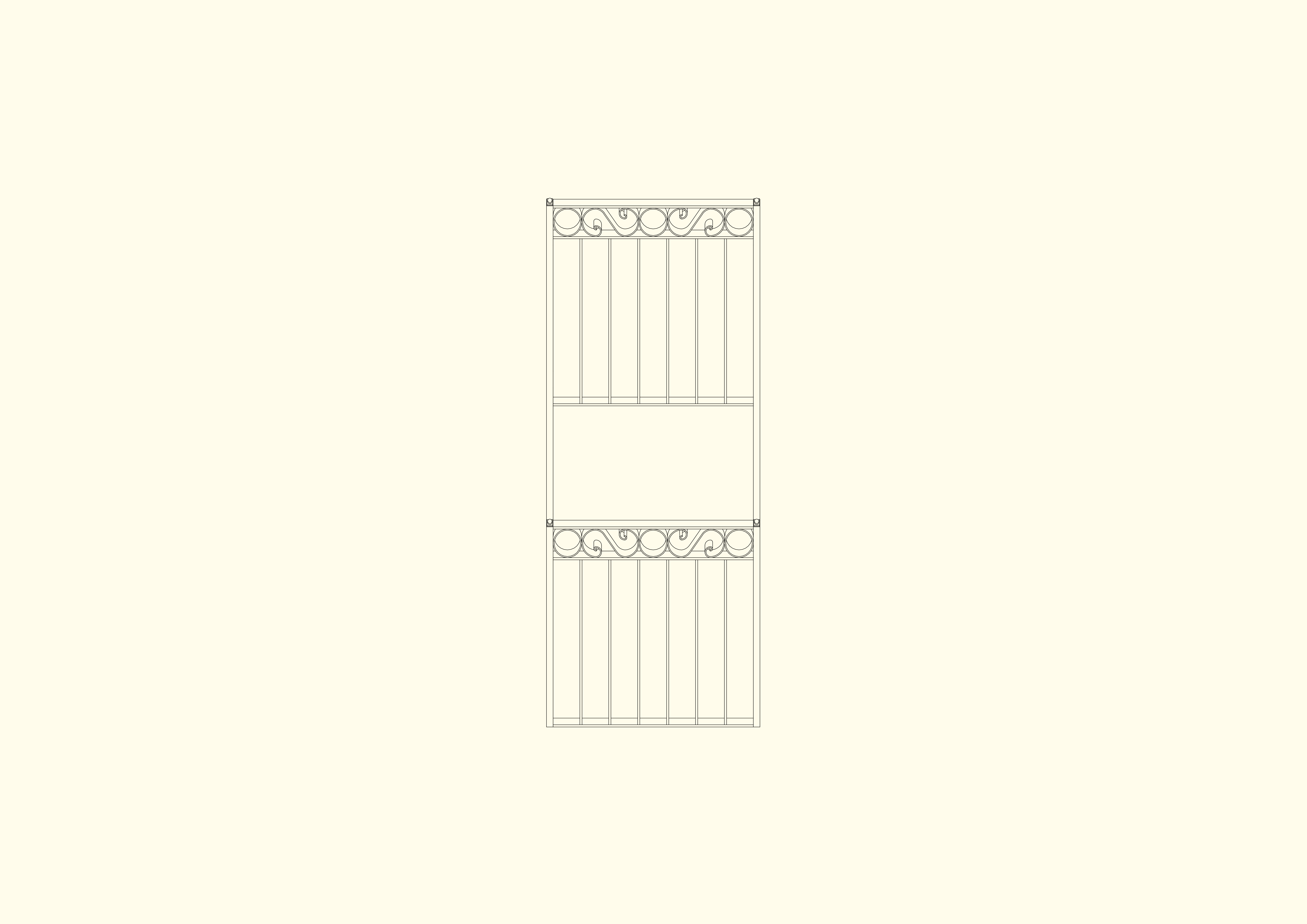

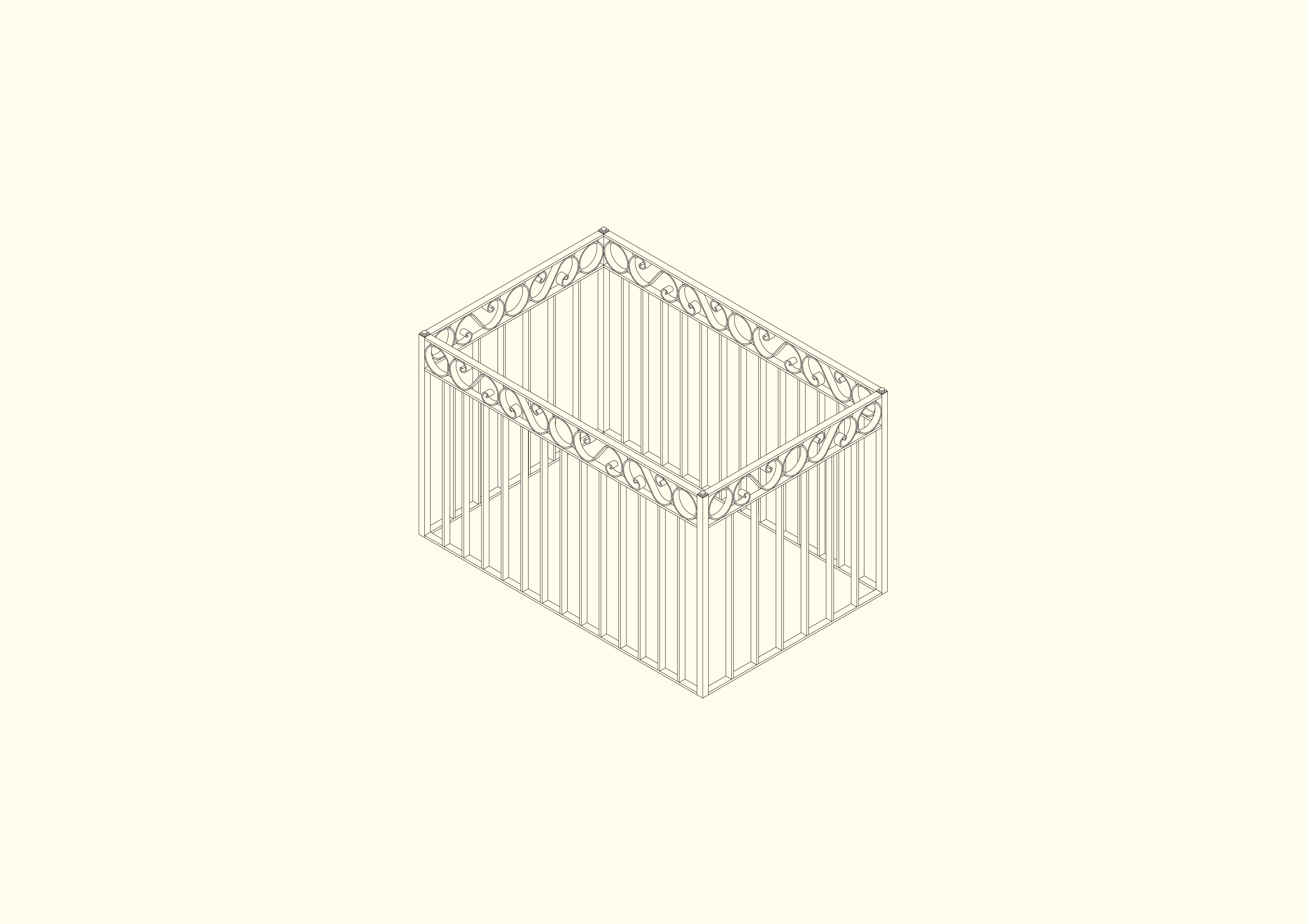

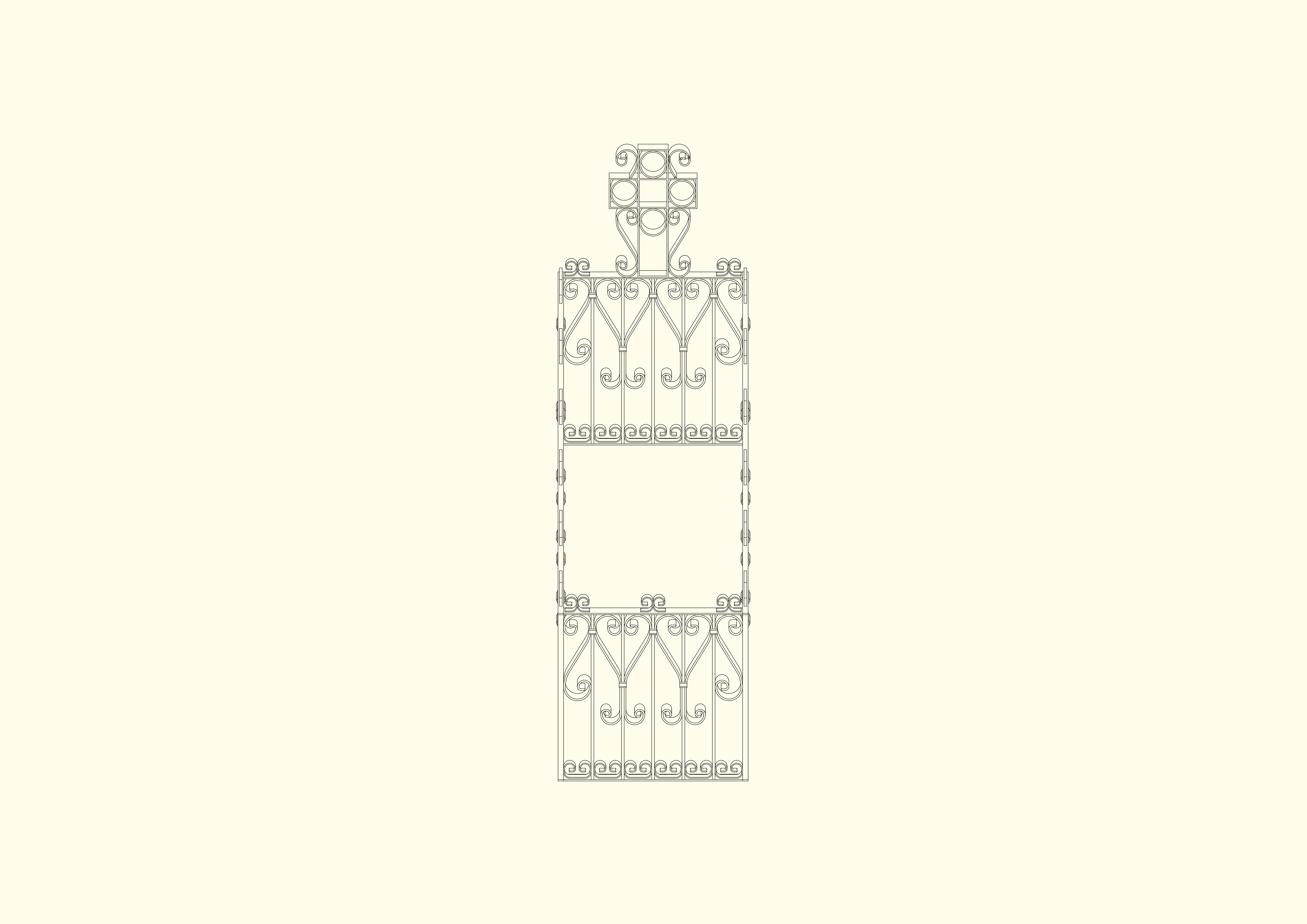

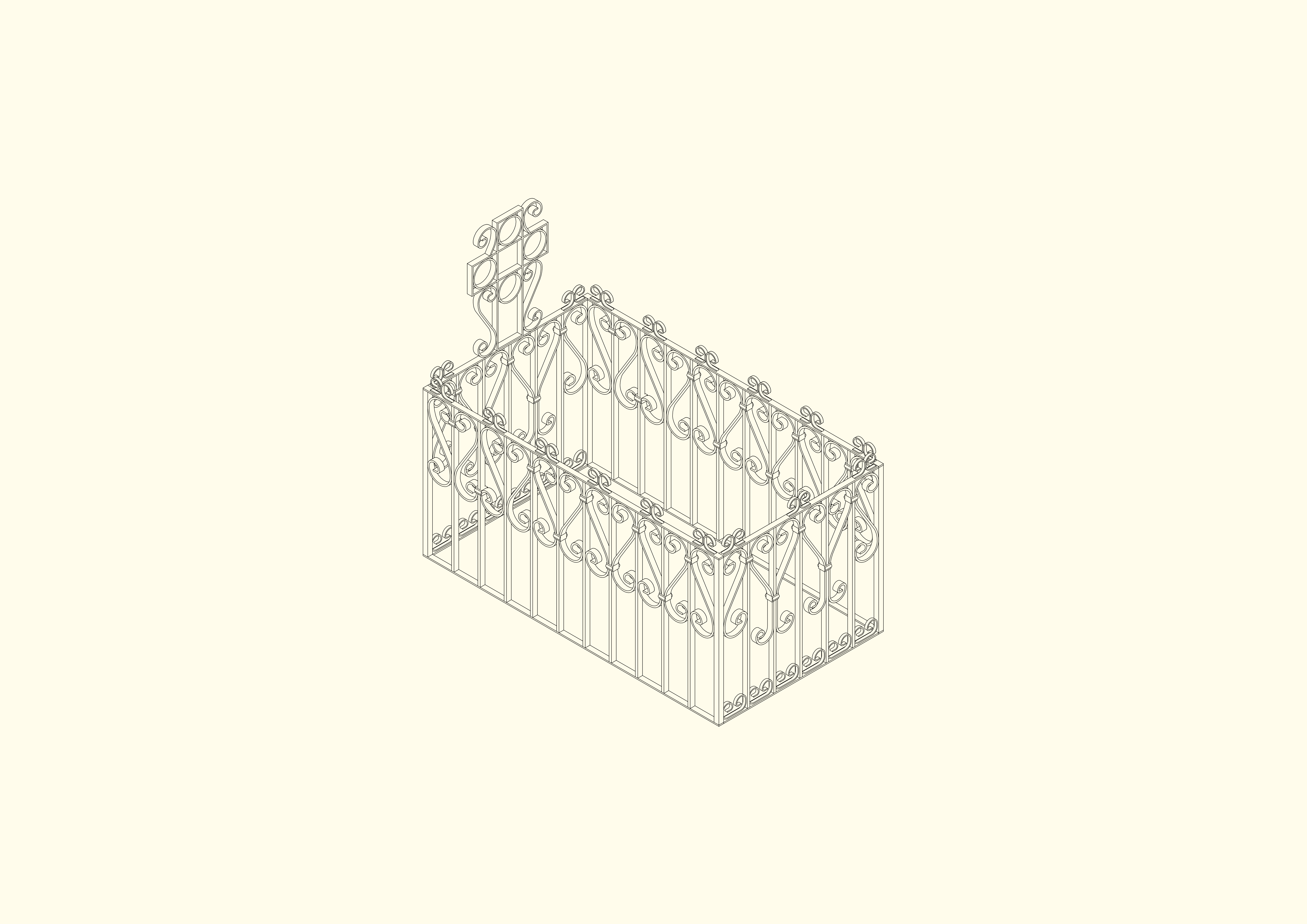

Depending on the period, the material construction of the grave fence changes, being possible to notice a greater thickness in those built in iron, with a more iconographically saturated ornamentation, with varied scrolls and foliations, and a closer proximity to the ground. These older perimeter fences come close at times to the definition of a cage, and some resemble the ‘mortsafe’ that emerged in British cemeteries to prevent desecration. The use of cast iron and later steel in the manufacture of funeral fences is accompanied by a standardization in the decorative elements, so it is possible to observe a smaller diversity of balusters, ferrules and appliqués in the recently occupied courtyards. Although the presence of Catholic crosses and motifs related to nature, mainly flowers and plants, continues to be the majority, this is complemented by a higher frequency of simplified patterns, such as vertical or diagonal profiles that reduce their function to limiting the gravesite without symbolic ornamentation.

Although it is possible to recognize marked temporal origins in the perimeter grave fences present in the General Cemetery, the group of fences is still diverse and eclectic: a great confluence of dimensions and styles. The lower grave fences are reminiscent of the fences of old front yards —still free from the obsession with residential security— evoking the image of paradise as an infinite garden, or in this case, the gravesite as a small piece of paradise. The tallest, are frequently reminiscent of baby cribs, or large beds depending on their overall dimensions, contributing to the soft imagery of death as a long sleep, as eternal rest.

As a more recent layer of information, there is a superimposition of later interventions: a perimeter that transforms and adapts: Candelabras, flowerpots, vases, small benches and ceilings complete the original projects. The permeability of the fence, from the space that exists between the elements that make it up, also allows it to become a memory support for the deceased: letters, photographs, toys and bottles brought by visitors.

Finishing this little walk and revisiting Adolf Loos’ rusty phrase ‘only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the monument and the tomb’1 undeniably related to cemeteries, it is possible to force a series of disciplinary provocations that allow us to investigate the fence as an object that overlaps with architecture, but also with art: an ambiguous limit sentimentally charged with ornaments that refer to symbolisms and imaginaries in relation to life and death.

- Loos, Adolf, et al. The Architecture of Adolf Loos : an Arts Council Exhibition. Arts Council of Great Britain, 1985. ↩︎