DEAR TO US

Contributor

Farewells

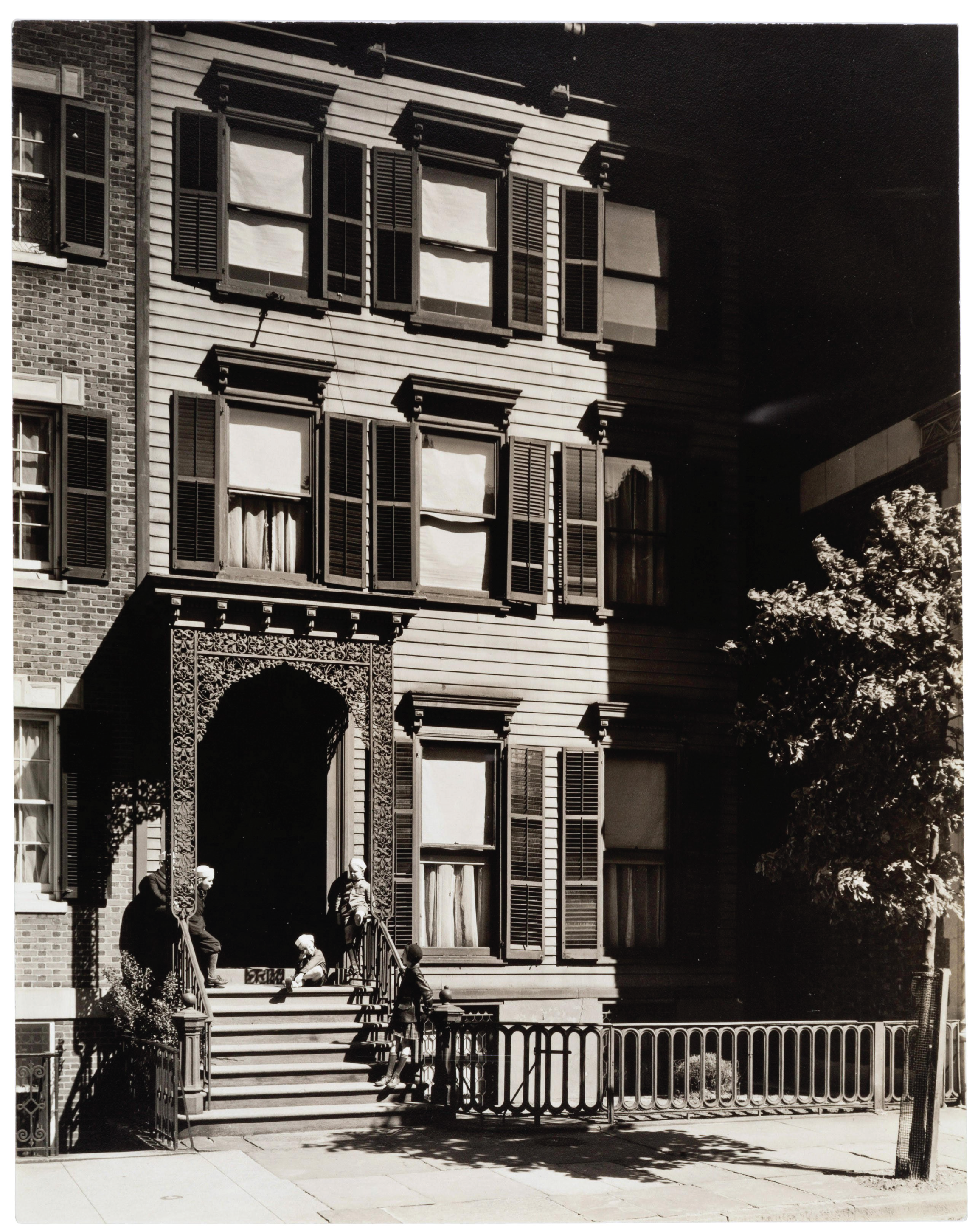

is the scent of joy, the sound of giggles, the tense air of kids forging a plan. Indistinct chatter, nudging elbows, a snapping trigger and … bang – birds are startled, dissolved into air. The sound of flapping wings drowns in the buzzing city life, the bird’s serene presence lost in the plain everyday. The sun’s glow renders the scene impeccable. A delicate iron flower bed crowns the casual conviviality like a profane halo. Protected through the sense of parental latency, the kid’s curiosity thrives ceaselessly. They steer through the wind’s waves like the toughest sailors, turning each urban calm into a storm of activity. Yet, a secret act of heroism is put forth by the girl some steps below. Up two steps from the street, she ties the boys to the urban realm, drags them into the uncertainty of the neighbourhood. The stair is populated like there never was a Great Depression, the last remnants of the ornate portal symbolically for everything that once was there.

This letter is an ode to the squeaking rocking chair, loosely stacked books, withered wood, knitted blankets, barking dogs, wasp nests, enthralling tales, beloved swings, tender serenades, sailor hats, lost wigs, broken boomerangs, crooked ceiling fans, silly toy guns, torn sun visors—all elements of memorable events. However, it’s not just individuated memories, singular perceptions and private stories that were once treasured between far and home.

The liminal space now in decline converges private and public, intimate and ‘extimate’ on multiple levels. Today, we seldomly live within the confines that were in a different place and time, more exquisite, more grand, more about us. Still present in the countryside, rarely seen in cities, is the liminal space that halts time. There lingers the mist of forgotten pasts and deep down, without noticing, it affects all of us. In our overwhelming nostalgic memory, we sense these scenes not only in the light of the shadow but as a whole, a vessel of life, containing bodies that grow. This ‘in-between’ orients the building, just like the directed limb articulates the entirety of a body. The domestic character is decided at the front door’s threshold, facing the communal realm. Its disposition seeks the marriage of house and street, relates architecture to streetscape. The fanciful wrought iron expresses, just like a vibrant silk dress, one’s sentiments towards the other. Yet, its existence is not just some sort of representational quality, but a penetrating reality that fosters conviviality. The liminal space generates a significant and ominous dynamic between a private and public world, an inner and outer existence, the simultaneity of the self and the others. It pushes you out into the world while being tightly fastened to home.

What triggers the absence of liminal spaces in today’s bustling city life? Is it the brutality of reality that prompts our desire for enclosed private life? What about the sociality of things, the locality of chance, a place for flowers?

Unfortunately, market pressure, housing deficit, building efficiency, and private ignorance swallowed the depth of our facades.

In today’s densely built environment, unforeseen collective experiences have no space. Entrances seem to enthrone penetrating inscriptions: ‘profit = erasure’ and ‘privacy knows only me’. And with such cultural loss comes the loss of such beloved events. Over time, the front door’s purpose, function, form and popularity have evolved as a reflection of changes in our lifestyle and social idioms. Only a tremendous shift back will enable the return of a semi-public space with a distinct sense of collective comfort. Is this all just nostalgic past and contemporary fiction – a meaningful get-together merely a mentally constructed phenomenon? Shouldn’t we dwell on today’s seeming void to excavate from it the latent potential that it holds?

Isn’t the front of our home the scene of give and take, anticipation and fulfillment?

We miss the conviviality of happenings, surprising chance encounters, in the brace of the wind, with the sprinkling of the rain at noon, playing cards, exchanging secrets, feeling part of one‘s shelter, yet also part of the exterior world. Once dear to us, was the place we could gather in front of the house, having private chats, providing a place for rest and wait, for owners and guests.

With the loss of the porch, we lost a safe space for collective play, collective rest, a place for welcoming family and friends and also a place of proper farewell!

We hope for a return of … Yours, us.

BERENICE ABBOTT, Willow Street, no. 113, May 14, 1936 [Variant] © Museum of the City of New York