The Making of a Cult Image

Contributor

Architecture Kool-Aid

In late 2018, it became evident to most trend-watchers and fashion magazines that the next season’s biggest trend would be… cult attire—from long orange tunics, smocked necklines, white frocks or sneakers, there was an obsession with the persona, the image or the collective look of cults. This sudden surge of interest in cult attire was in direct response to a surge of films, TV shows and documentaries all making their mark in the cultural zeitgeist—Wild Wild Country, American Horror Story, Waco. The fascination with such groups and charismatic figures would persist with the release of Midsommar and the consumption of crisp, white embroidered frocks. It is not at all unusual for strong visual identity to be heavily focused on and controlled in cults—leaders use it as a mode of recruitment, a way to lure in followers with their seductive image…

Pedro E. Guerrero, Frank Lloyd Wright, Tea Break #2, Photograph, Guggenheim Pavilion, NYC , 1953

Afterall, clothing and appearance are key players in the making of an identity. Take uniforms for example, not only do they allow for an outsider to identify you, but have a way of reshaping how you see your own identity. Cult clothing is a signifier of just how strong a cult’s power is. For architecture, the most obvious element of the uniform is the color black, it is part of the identity of the profession. Entire books on the question have been made. In Why Do Architects Wear Black, a large number of well-known architects admit, they do not know “why architects wear black.” Really the act of wearing black for some is a ‘non-decision.’ It is a dress code established by the profession as opposed to a choice made by the individual. Though strangely, the cloaking of wearing all black to the general public is also seen as an indication of mystery, intelligence, sex, introversion and silent self assurance. The cloaking of all black—as if we were part of an organized religion1 —becomes a way of establishing a group identity—one that distances itself from and exposes outsiders—an alarming tactic for a service industry.

Photograph at Pratt Institute Gala and Mary Buckley Dinner honoring Philip Johnson c.1990.

Another classic image and accessory to the architect are the thick, black round-framed coke-bottle eyeglasses. Such eyeglasses became a crucial identifying element for stars like Philip Johnson and Corbusier. Johnson became so synonymous with thick round spectacles that it became a tool in the public circulation of his face– entire dinners cloaked their faces in the spectacles. The trademark became so ingrained in his image that in the 1984 AT&T Building, he formed his own image in his own creation.2 A creation made in his likeness. Afterall, there is a history of architects being ordained by the divine—a key element in cult image making. Leaders are often experts on distinct aesthetic image making as a means of alluring outsiders in and establishing loyalty. Consequently, this becomes the image in which the field of architecture communicates with the public.

David Levine, Drawing of Philip Johnson, New York Review, 1994

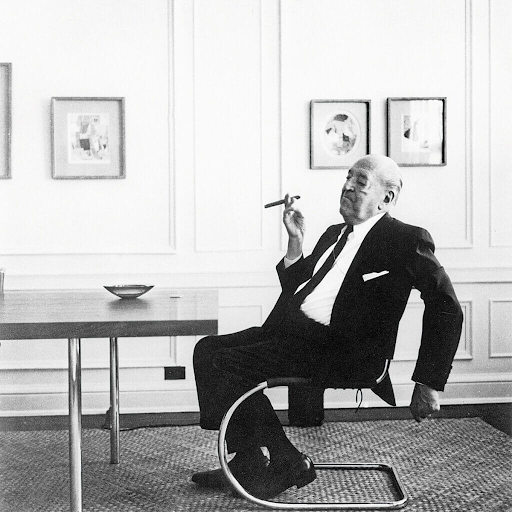

Mies van der Rohe was an expert at this. Our entire vision of Mies and his work is one of theatrical illusions.3 Not only was Mies strategic in his use of a pseudonym4 but he specifically omitted the bow tie that had become entwined with the uniform of the architect at the time. The bowtie signalling entitlement and class (I suppose I do not need to point out how the image of the architect with this attire specifically implied the image of the architect is that of a white male). Photography and public image were crucial in the making of Mies van der Rohe and helped establish his staying power in the pedagogy and profession of architecture. Sifting through photos of the lone man, he consistently sports a dark tie, crisp white button up, double breasted suit and pocket handkerchief, he is never out of uniform—A uniform that reflects the serious respectability of male-dominated corporate America.

Werner Blaser, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe in his Chicago apartment, Photograph, 1964.

As Beatriz Colomina has stated, modern architecture was produced within the site of mass media, one composed of images rather than within the confines of walls; Architecture was a commodity. In this consumer culture, where the architect becomes yet another consumer choice, product and person become inseparable.5

Landmarks and Follies, Beaux-Arts Architects Ball, Ely Jacques Kahn (Squibb Building), William Van Alen (Chrysler Building), Ralph Walker (1 Wall Street), Photograph, Beaux Arts Architects Ball, 1931

Let us dig into how this has played out more carefully…Consider Apple’s 1998 “Think Different” campaign that showcased the company’s definition of “genius”. It shows Gehry in front of his then newly-built Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain. The banner is not on a billboard but on “his” building, the Binocular Building. Apple is attempting to be “hip”—the viewer is supposed to relate to “the independent, affluent, confident male individual”.6 Hip becomes a way to universalize the experiences of the elite white male socioeconomic class and becomes a means of bringing corporate colonization to everyday life, as noted by architect and critic, Tom Frank. Moreso, the very idea of a creative genius is based on the image of the white male—for us most notably Frank Lloyd Wright— which the hero architect of The Fountainhead is based on. The very depiction of architecture in this manner makes the field inaccessible…It is no wonder architect and critic Tom Heath refutes the idea that architecture is a service. Such illusions of individuals can so easily be used for selfish gains and to bully clients and patrons into carrying out their fantasies.

Frank Gehry in Apple’s “Think Different” ad (portrait of Frank Gehry by Todd Eberle taken at Bilbao), Chiat/Day building, Los Angeles, 1998. Photo ©2017 Todd Eberle.

Looking closer at the image, Frank Gehry looks leisurely, relaxed in his loosely buttoned shirt and tousled hair. Is he carefree? Diane Favro finds this depiction of the male architect common—he is self-assured, and an individualist. She says that typically while the male is leisurely, the woman is often depicted as being white, and dressed in generic suit attire. She is a professional above all else but he is an individual hero, he is an architect. Sporting a black coat and black rimmed spectacles whilst smoking (another popular element of the architect, one that filled the studio with a mysterious alluring veil), he is the architect. His guise is projected to the public as the image of the profession—an ideal and a leader in the field.

Cult leaders tend to be successful at controlling the masses by producing an alluring fanciful, almost godlike, depiction of themselves—an image to be admired and to be made again in his likeness. So we sit, with our caffeinated drinks in our black attire and trendy glasses, sharing stories of lore. Sleep deprived, we fix our studio ‘errors’ and study a fame-forward architecture carried out by a mass media that is obsessed with personas.

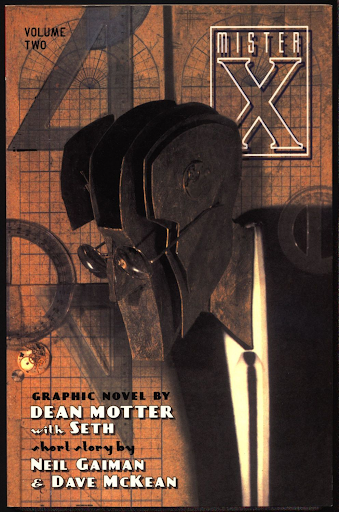

MISTER X: The Definitive Collection Vol 2 Cover Art, Dean Motter,Seth, Neil Gaiman, Dave McKean, Radiant City, Trade Paperback Comics Collection, 2005

The criteria of what is good and what is bad in architecture remains ill-defined, and thus we rely on the rituals of stars of a past life. How smart the cult of architecture is to develop an army of introverts and lone-geniuses, who have been led to believe the collaboration is a compromise. Alas, like all good cults, we have begun to implode as we start to see behind the veil. We are all too aware and equipped with the tools of personal branding and image making; We are all experts of self invention. The myth of the individual hero is breaking down. Will we be able to accept our humanity?

The image of the architect is a myth and we must stop worshipping cult leaders– we must move beyond myth and fantasy. W. J. T. Mitchell has a pointed metaphor for images and their lives. He uses an image from Jurassic park.7 The image here of the myth that life begins with the word of god—the image, as we know, ends with that which has been created seeking to destroy the creator.

- “Architects are missionaries. - Hermann Kaufmann” Rau, Cordula. Why Do Architects Wear Black?: . Berlin, Boston: Birkhäuser, 2017. ↩︎

- Schnapp, Jeffrey T. “The Face of the Modern Architect.” Grey Room, no. 33 (2008): 6-25. Accessed August 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20442806. ↩︎

- Colomina, Beatriz. 2014. Manifesto architecture the ghost of Mies. Berlin: Sternberg Press. ↩︎

- Originally Maria Ludwig Michael Mies, Mies added his Mother’s surname “Rohe” and added “van der”, since he could not use the German “von der” as it was relegated only to noble heritage as a means of offsetting “mies” which translates to “lousy”. ↩︎

- Colomina, Beatriz. 1996. Privacy and publicity: modern architecture as mass media. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. ↩︎

- Hornbeck, Elizabeth. “Architecture and Advertising.” Journal of Architectural Education (1984-) 53, no. 1 (1999): 52-57. Accessed August 15, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1425559. ↩︎

- Spielberg, Steven. 1993. Jurassic Park Still. United States: Universal Pictures. ↩︎