Excite and Offend

Contributor

Architecture Kool-Aid

In the end of year review of Unit 10 at the Architectural Association (AA) in 1983, external examiner James Stirling dramatically dismissed the group of students as unworthy of their diplomas. Such experiences haunt the anxious minds of architecture students everywhere, but it was from this that the young group along with their tutor built something bigger than each of their individual portfolios. Emerging in opposition to the optimism of groups such as Archigram—whose utopian visions had long dominated the ideological position of the school—Unit 10’s newly politicised agenda for architecture inspired a “postmodernism of resistance.”1

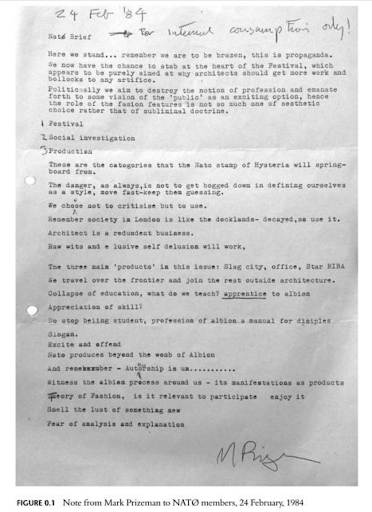

The students, together with their tutor, formed NATØ—Narrative Architecture Today—a collective that would produce a new stream of architecture discourse, beginning from the bold declaration written in an early memo by member Mark Prizeman that “Architecture is a redundant business.” The work of the Unit was anarchic and unorthodox. Headed by Nigel Coates—who had taken over the Unit from Bernard Tschumi—the students developed an approach that took on the flavour of emergent popular culture—fanzines, music videos, street life, nightclubs, fashion. This melange of influences and their expression in the unconventional work of the Unit struck such horror in the figures of authority at the school that it was deemed un-examinable. It marked the birth, however, of arguably the “last radical architectural group of the twentieth century,”2 as remarked by Claire Jamieson who recently chronicled the previously undocumented activity of NATØ after its inception.

Is it possible that such movements—cohesive architectural moments—can emerge out of schools today? Is it still possible to be radical? NATØ arose out of a particular set of conditions—a derelict and decaying London in the ‘80s—that no longer exist, but understanding its ingredients might be useful to students wanting to question the current state of education. Intensely provocative, the work sought fresh options for architecture by drawing on what was outside of it, refusing the self-referentiality of prior architectural discourse. Still seeking alternatives to Modernism, architectural schools in the ‘70s had developed a “dull specialism and narrow parochiality,” as the editorial team of the Architectural Review had so frankly remarked in a special 1983 issue dedicated to reviewing the school. NATØ claimed autonomy from the profession and took a stab at its authority. It refused to be polite or to adhere to the obsession with form that had since preoccupied architectural culture. The leadership of the AA at the time and the collection of tutors clearly had a decisive impact on the direction of the school and the exploratory conversations it engaged in. Figures like Coates and Tschumi, as well as Elia Zenghelis, Dalibor Vesely and Peter Cook, played a strong part in cultivating an intensely rich academic environment. It seems the conditions that render schools pockets of resistance—that give them the energy to produce new discourse from within the arena of architectural education—depend on a certain constellation of engaged tutors with shared motivations, but also willing students and a considered engagement with the force of external social and political circumstances.

Perhaps now more than ever before, architectural students are conditioned to identify with those in the professional class, informing how we relate to one another in our careers and in school. After waves of successive tuition hikes, departmental budget cuts, ever-worsening job prospects in a discipline seemingly concerned only with profit, and labor expected for free—all exacerbated by the force of the pandemic—it is no wonder that today’s architectural student might be unwilling to take such risks in their school work. The marketization of education has twisted the relationship between the student and the institution into one of mere transaction. In this bleak scenario the student is a consumer, seeking to extract all they can in a bid to claim the most for their time and money, a desire driven by the need to survive after being thrown into practice. It is a competitive job market, they say. “Build your portfolio accordingly.” Such individualization precludes experimentation. With the extent of the mental health crisis within architecture being rendered ever clearer, taking time to explore and test is increasingly confined to the safe boundaries of what is already deemed acceptable.

Within this hostile context, there are students guided (and sometimes un-guided) by design tutors producing work that excavates, challenges, and transcends its conditions. Today, it might require a complete reimagining of the University as a site of learning and a greater awareness of how we associate with one another during our education and early stages of our careers. These questions are partially being addressed in places such as the University of the Underground and the London School of Architecture. Beatriz Colomina together with a team of PhD students from Princeton University have an ongoing project to map and describe intense —though short lived—experiments in architectural pedagogy. This essay is too short to evaluate their various successes and shortcomings, but it remains a site for further inquiry. Creating something new without chasing novelty—refusing the kind of privatised knowledge of intellectual property and the individual designer—is possible. To all of us entering into physical proximity with each other for the first time in over a year, this is an invitation to be brazen. Excite and offend. I wonder how we—together—might “travel over the frontier and join the rest outside architecture.”3