Plastic’s A Beach

Contributor

Yuck!

“Plastic is wholly swallowed up in the fact of being used: ultimately, objects will be invented for the sole pleasure of using them.”[1]

–Roland Barthes, Mythologies

“Plastic engages in brief and sometimes quite spectacular transformations at the beginning of its life cycle but then is discarded, left with a molecular structure that holds onto its stability at all costs.”[2]

–Heather Davis, “Toxic Progeny:

The Plastisphere and Other Queer Futures”

In July of 2019, Thing Thing was invited to participate as artists in residence on the Big Island of Hawaii. We came armed with luggage full of tools and a vague knowledge of ocean plastic and its burden on beaches around the globe. This was our first visit to Hawaii; the residency was an opportunity to gather knowledge from a new place, to listen, and to physically experience/discover the reality of a global industrial waste crisis.

The currents around the Hawaiian archipelago have always deposited items from across the world along the southern coast of the Big Island. This coast was once known as a place to salvage large driftwood from the pacific northwest or find rare coveted stray glass lures from far away Japanese fishing boats. Now these same currents connect the island to the Pacific Gyre and the Great Pacific Garbage patch, depositing hundreds of tons of waste plastic on shores of Kamilo Beach.

Curiosity brought us to this place, colloquially known as “plastic beach.” Tragedy and horror met us there. The coastline presented a devastating toxic landscape mediating miles of lava rock fields and open ocean. The amount of waste here is insurmountable. It is estimated that 90% of the beach is now plastic—some large pieces, but most have been broken down. A handful of Kamilo sand is a technicolor index of consumer waste, fragments scoured and polished by ocean waters.

For us, the ocean provided a way to reimagine and engage in this place—to conceive of the beach as an opportunity, providing an unending amount of raw materials to be collected. Materials symbolizing both the ingenuity of humanity and our incredible irresponsibility. Into our hats, dispersed along the coast, we picked handfuls of plastic. We filled buckets—each piece observed and chosen.

Next, we sorted. Starting from a single pile of beach rubbish, a slow and painstaken spectrum began to emerge. We became intimate with our collection. Every piece touched, picked up and tossed into its right place until only a rainbow color wheel of plastic bits remained.

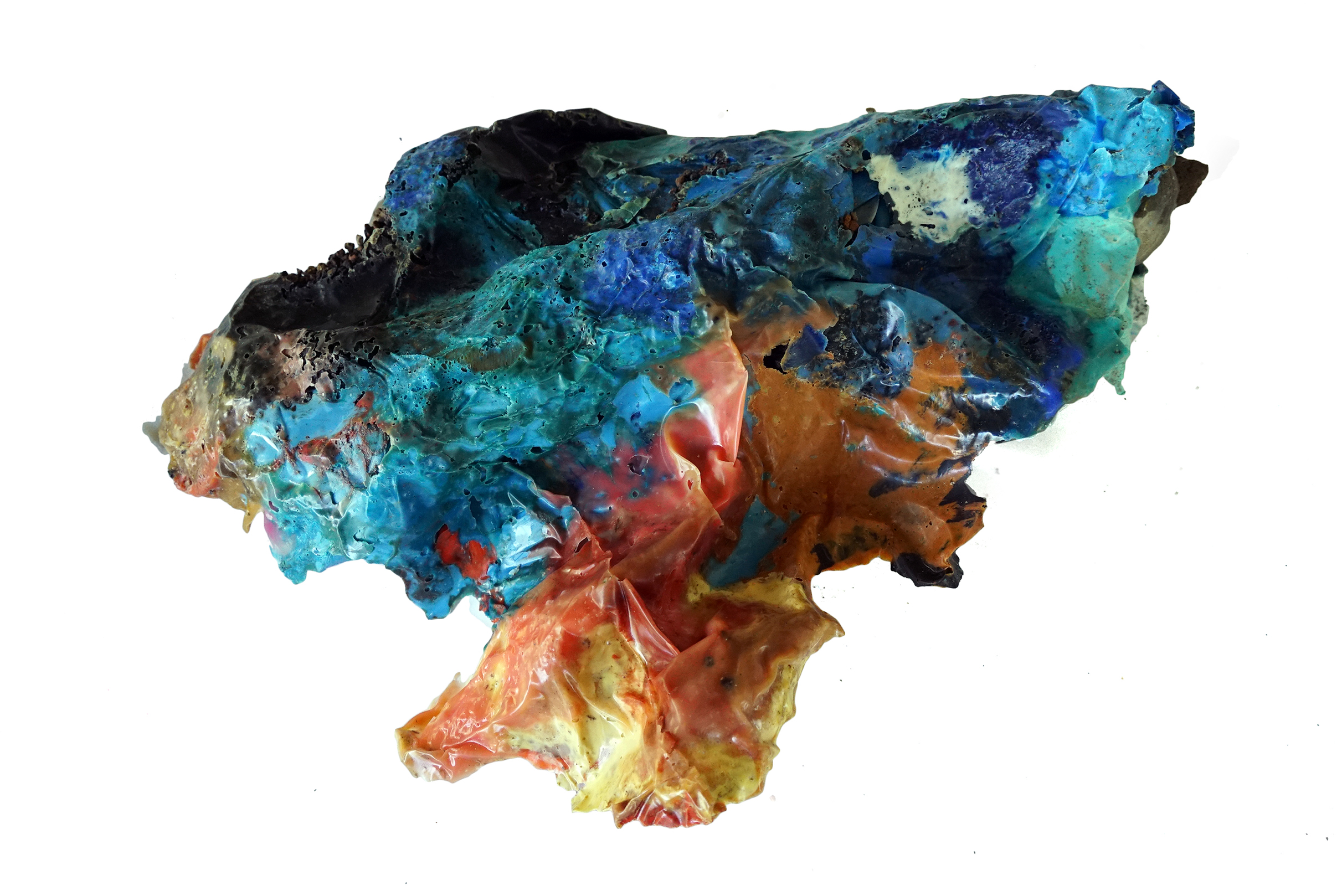

Hawaiian lore boasts of the power of lava rock, and warns visitors to leave the rocks undisturbed. Inspired by rocks belonging to the island, we set out to make pressings of the spectacular lava formations with heavy aluminum foil. These would be the molds for the object we make from the plastic collected on the beach—a nonnative newcomer.

Using fire oven techniques, we melted plastic into open molds, creating two-sided objects: one face formed in the likeness and texture of lava stone, one face revealing traces of its origins.

“So, more than a substance, plastic is the very idea of its infinite transformation; as its everyday name indicates, it is ubiquity made visible.”[1]

More than just infinite transformation, plastic is of infinite scale and time. The problem of waste is huge and incomprehensible. It is at the human scale, sitting on a beach staring at handful of plastic sand, that these scales converge. We can understand something tactile in the infinite; something beautiful in the yuck.

Thing Thing are the Detroit-based experimental designers, Rachel Mulder, Simon Anton, Eiji Jimbo and Thom Moran, specializing in research in waste material and industrial processes, specifically focused on plastics. Plastic’s A Beach is a part of Kindred Spirits, an Exhibition of Temple Children Residency. Opening Nov 1st.

[1] Barthes, Roland. Mythologies: Roland Barthes. 1972. New York:

The Noonday Press, 97-99

[2] Davis, Heather. “Toxic Progeny: The Plastisphere and Other Queer Futures.” philoSOPHIA 5, no. 2 (2015): 231-250