Against an Architecture of Enjoyment

Contributor

The Architectural Gaze Goes Clubbing

On Saturday, June 19th of 1965, a discotheque named Tiffany’s opened in Platja d’Aro, a small tourist town on the Spanish Costa Brava. Purpose-built, it was one of the earliest modern discotheques on the Mediterranean coast, and “the best of its kind in Europe,” said Georgie Fame. Four years later, on August 24th, 1969, Francesc Tubáu Subirat, aged 18, drove a motorbike without a license to the entertainment venue’s doors. He placed eight dynamite cartridges and a detonator on the roof of the club with the intention of blowing it up.1 It was Monday at 2 am and around 800 people gathered on the dance floor. The explosion could have killed many of them, yet Tubáu was startled by a waiter before having a chance to detonate. Fleeing away, he fell unconscious on the street and was arrested. A summary court martial condemned him for terrorism to 18 years

of reclusion.

Exterior view of Tiffany’s in late 1960’s. Picture from the collection of the Municipal Historic Archive of Castell-Platja d’Aro. Author unknown.

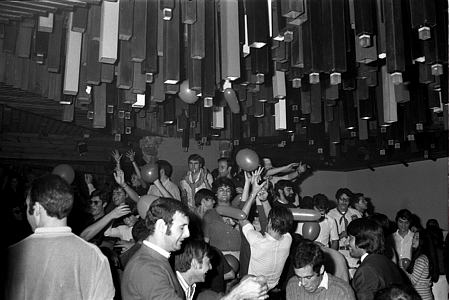

Interior of Tiffany’s on the night of the 12th of October of 1969. Picture by Narcís Sans Prats, from the collection of the CRDI (Centre de Recerca i Difusió de la Imatge), Catalonia

Tiffany’s was an innovative piece of architectural design: a box of around 600m2 that electronically produced an artificial interior atmosphere. The building had no openings besides the entrance door. It was wrapped with multiple layers of insulation, creating an interior space completely segregated from exterior reality. Inside, electronic technologies were used in an innovative way: an electronic core, situated in the center of the building, contained the necessary machinery for the control of 400 points of flickering coloured lights and a stereophonic sound system.2 The sum of lighting and sound technologies, with the help of some stimulating drugs,3 created an adjustable atmosphere that exalted the senses and synthetically produced pleasure.

Though, in one sense, Tiffany’s provided an exceptional emancipatory space from the constraints of the industrialized city, it nevertheless also demonstrated an individual instance of a larger transnational project for the commercialization of enjoyment: the tourist industry. Through uniting technology and bodily pleasures, the discotheque emerged as the most advanced architectural typology conceived by the tourist industry; one that allowed to sell pure joy. Tiffany’s became a paradigmatic example of the virtues and excesses of the tourist economy.

Since mid 1950’s, the Spanish dictatorial regime promoted tourism development along the coast, offering loosened regulations and low land prices, thus channeling money down from northern European countries. In fact, Tiffany’s was created by two Swiss entrepreneurs,4 reflecting a larger trend in the country of foreign tourist investment. In 1969, Platja d’Aro was a village of less than 2,500 inhabitants,5 yet there were at least six night clubs with capacity for more than 5,000 people.6 These discotheques, and many others that spread along the coast, were a constituent part of the tourist ecosystem, which included many other pleasure-related infrastructures, like aqua-parks and chiringuitos,7 catering and hospitality services. Platja d’Aro was in the area of Spain with the highest density of tourist facilities,8 with more than 500 hotels spread across 30 kilometres of coast.

DJ Jean-Pierre Grätzer (with glasses) at Tiffany’s deck in 1965. Picture by Erich

Bachmann, private collection.

Tubáu was a progressive son of an affluent family who had occasionally engaged in modest actions against the regime, such as graffitiing walls or printing posters. Taken with anarchist and socialist theories, he wrote a plan of action in June of 1969 that included “direct action in all its forms: from individual bombs to the armed guerrilla group.”9 The text sounded more like a political declaration than a realistic plan for execution, yet the solitary attack was perpetrated. The bomb in Tiffany’s marked an overlooked turning point in the history of Spain. Even if the means can be questioned, the motivations were clear: to denounce the collaborative relationship between tourism and dictatorship and, furthermore, to denounce spatial exploitation. As Lefebvre outlines in his text, “Towards an Architecture of Enjoyment,” the development of the tourist industry was a process of the neo-colonization of space.10 The attack made visible the contradictions of the dictatorial regime but also unveiled the dangers of a new and upcoming form of capitalism. From Rimini to Torremolinos, the Mediterranean discotheque rendered evident the start of an era in which spatial experiences were not only to be industrially produced, but consumed en masse. The consequences of this paradigmatic change are still resonating today, while the battle started by Tubáu is still being fought against new forms of spatial consumption.

After the end of the Spanish dictatorship, Tubáu managed to leave prison,

aged 25.

- Castillón, Xavier. 2012. Nits d’Aro. Seixanta anys de discoteques i sales de festa a Platja d’Aro. Castell-Platja d’Aro: Ajuntament Castell-Platja d’Aro. p. 97-101. / Gasull, Joan. 2017. El pacifista que pretenia volar una discoteca. Girona: Llibres del Segle.

- A description of the interior of the club can be found in an article published in the Spanish newspaper Los Sitios de Gerona, on the 24th of June of 1965, p. 9.

- Antonio Escohotado, Spanish thinker recognized for his research on drugs, explains how Spain was the only Western country that didn’t take any action against certain drugs, like amphetamines, after the American Drug Acts of 1964 and thus became known for its drug consumption tolerance. / Escochotado, Antonio. 2018. Historia General de las Drogas. Barcelona, Espasa Libros. p 764.

- The identity of the initial investors have been registered in a series of legal documents preserved in the Municipal Historic Archive of Castell-Platja d’Aro in Catalonia. Their names were Raito Ganzoni and Werner Straub, and they were both Swiss.

- The data is reflected in the population chart published in P. Barreda i Masó, Platja D’Aro. Quaderns de la revista de Girona, Girona, Diputació de Girona/Caixa de Girona, 1996, p. 9.

- The calculation comes out of the research conducted in the Municipal Historic Archive of Castell-Platja d’Aro in Catalonia, where historic documents and permits can be found in relationship to the clubs.

- Chiringuito is a Spanish word for beach bar. Typically a simple construction sitting next-to the beach and providing food and beverages.

- A complete study on the impact of tourism in the area of Costa Brava until mid 1960’s was conducted by Yvette Barbaza in the French CNRC (Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique) and published in her book Le Paysage Humaine de la Costa Brava. Barbaza, Yvette. 1966. Le Paysage Humaine de la Costa Brava. Paris: Librarie Armand Colin.

- The full action plan is published in El pacifista que pretenia volar una discoteca. / Joan Gasull, Joan. 2017. El pacifista que pretenia volar una discoteca. Girona: Llibres del Segle. p.137.

- Henri Lefebvre addresses the topic of tourism, space, and architecture in his text “Toward an Architecture of Enjoyment”, a piece that he wrote after a commission from the Spanish sociologist Mario Gaviria in 1973. The text has been recently published in Lukasz Stanek (Ed.), Henry Lefebvre. Toward and Architecture of Enjoyment, London, University of Minnesota Press, 2014.