Lesbos: The Possibilities of an Island

Publics & Their Problems

DAPHNE AGOSIN and GREGORY CARTELLI

The word island comes from the Latin word insula and the old French word isle – the meanings behind which refer to the idea of detachment and formlessness. The defining characteristics of an island appear to be “smallness” and “remoteness”.

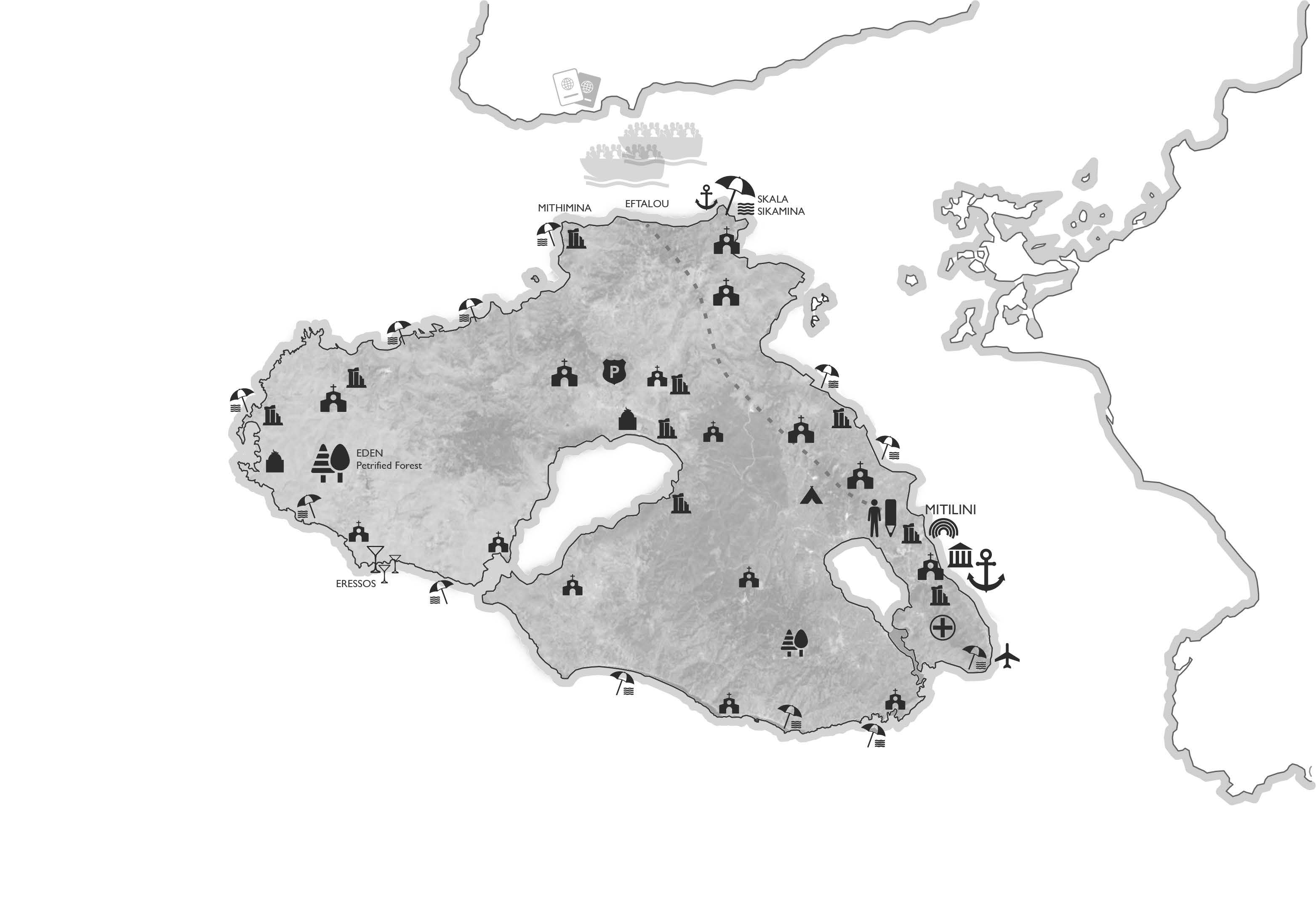

There is a sense of freedom in the idea of an Island, apart from the world, surrounded if not moved by the tidal flows and currents of the ocean, unshaken by the tectonic frictions of continents and countries. The clearly defined edges of islands sustain specific identities and create a mythological allure for the rest of the world. Lesbos, our island in case, is a place of unique identity. The 2008 publication “Walking Trails of Lesvos” outlines eighteen routes through and around the island, encompassing national parks, heritage sites, byzantine churches, Sapphic tourist destinations, resorts, and beaches. However, in light of recent events, there may need to be a new path added.

Six miles off the western coast of Turkey, the northernmost shore of the island of Lesbos has been the point of arrival for a growing number of refugees and migrants since at least 2009. Among this group are Syrians, Afghanis, Iraqis, and others, and in 2015 alone, roughly 164,000 displaced people have arrived here, far outnumbering the nearly 80,000 tourists who visit Lesbos each year. Their journey doesn’t end at the beach, however, as these migrants are then forced to make their way, on foot, twenty-five miles south to the island’s only processing center in Mytilene.

Thus has the touristic imaginary of Lesbos been compromised. No longer a place apart, a paradisiacal setting; no more the longed-for peaceful abode, surrounded by deafening ocean. Perhaps the image of this place has always been an illusion, constructed by guest and host alike. The island’s international marketing has long made note of its remote location relative to other islands, such as Mykonos or Santorini. Lesbos is “more than just another Greek island,” we are told, remaining “virtually unaffected by mass tourism.” The island’s petrified forest, its wetlands, castles, mosques, churches, and beaches all make the case for Lesbos’s exceptionality as a non-traditional tourist destination, and in 2009 it was awarded a “European Destination of ExcelleNce” (EDEN) award, its cultural heritage protected by national legislation, its economy both self-sustaining and locally managed.

This year the island has been both terminal and terminus for a new group of arrivals. Souvenir sales have dropped in parallel with a decline in tourism, while camping equipment continues to fly off the shelves. Will the forces of capital respond to this bottleneck in global urban migration, shifting the Lesbian economy into line with the needs of the island’s new guests? In this potential future, how will a culture built on hospitality respond to this new economic necessity? Its identity born, in part, from isolation, can Lesbos evolve into something different, an immigration portal in both identity and use, a front door, as it were, to Europe?

Local resident responses to the influx of refugees range from the sympathetic and compassionate to the fearful and conflicted. Some see little more than a shift in client base – where once there were tourists, now stands the International Rescue Committee. Others simply struggle to make do in the face of cancelled reservations. Local sympathy for the plight of the migrants may be due to the island’s own diversity of historical and cultural identity, having fallen, at one point or another, under Persian, Genoese, Roman, Turkish, and Greek control. Still, the island’s micro-economy struggles with the physical and practical realities of its own fragility. Operational and waste-collection services are overburdened, new refugee processing centers have yet to be built, and more buses are desperately needed to move the island’s growing population around.

The authorities of Lesbos have made official calls to the EU for help, appealing for material support in line with the trans-European policies they now struggle to follow. The “1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,” like the resolutions adopted in 1967 in the spirit of that protocol, make clear the rights of refugees to non-discrimination, non-penalization and non-refoulement – the prohibition of expulsion. Although assembled in good faith, this document fails to take stock of the socio-spatial realities of contemporary Europe. Whereas before the European Union, the “the Contracting State in whose territory (the refugee) is residing”— that is, the signatory state where a refugee happened to land – was considered to be responsible for the provision of all guaranties and protections under the convention, today that burden falls on the weakened economies of the EU’s southernmost member states, which serve as the Union’s physical gateways.

Heritage in Lesbos is a palimpsest of diverse cultural fluxes across and throughout history. Today, the state of the displaced is one of precarious street life, insalubrious refugee camps, and a complex culture of mutual distrust. An effective, and rapid, socio-spatial reconfiguration is demanded of this small island. What architectural dispositions might address the momentary reality in which the diverse-but-particular community of contemporary Lesbos – one comprised of residents, refugees, tourists, and volunteers – is immersed?

Images:

Statue of Liberty, Mytilene

Author: Μιχαήλ Δεληγιάννης

Map of Lesbos, with legend

Daphne Agosin