Counter-Planning from the Cruising Grounds

Contributor

Provisionally Together

In my project on the Italian queer movement in the 1970s and the emergence within it of a coherent vocabulary to speak, at once, of minority identity, oppression, and late capitalism; the politics of sexuality and space intersect in unexpected and at times baffling ways. One of the questions that Italian Gay Liberationists routinely grappled with was: How do you translate one of the key slogans of US-based Gay Liberation – Come out of the closets into the streets! – into Italian? The point of translating in this case was emphatically not to provide a “faithful” version of the original, but to produce a queer rallying cry that would be politically cogent for an emergent social movement that took sexual identity as one of its chief tenets. Importantly, because of its location within a wider radical anti-capitalist youth proletarian movement, the Gay Liberation Movement was simultaneously wary of producing a “single-issue” critique. What seemed most unsatisfactory to Italian activists about the English-language slogan and the discourse circulating around it in radical United States-based gay collectives, such as the Gay Liberation Front, was the reductive rendering of oppression through the metaphor of the closet – as a closed off, separate space. For this reason, Italian queer collectives looked for alternative spatial understandings of what it feels like to be an oppressed minority in late capitalism.

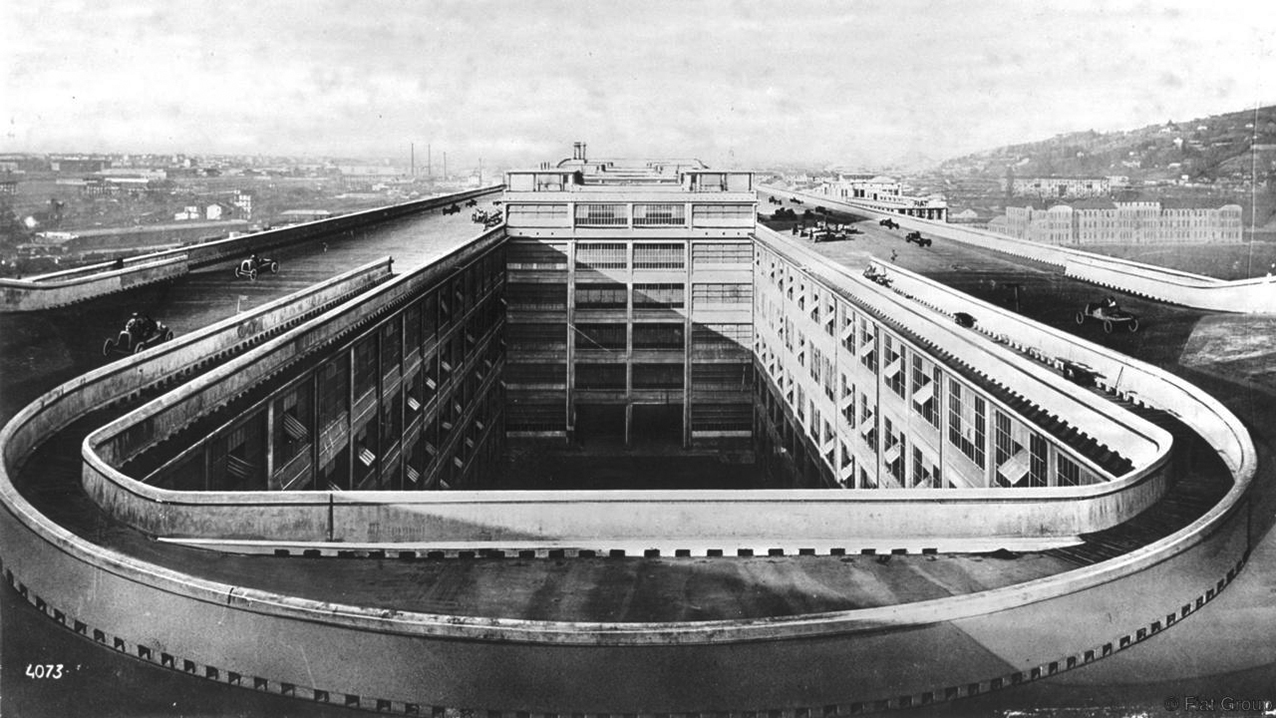

A Turin-based collective made largely of FIAT workers who worked at the Lingotto factory (the building that became central to architectural debates on space and reform) and were previously members of the autonomist groups Potere Operaio and Democrazia Proletaria is a case in point. At the start of 1977, when this group of factory workers came out as gay and were no longer interested in organising with straight factory workers, they formed the COSR, Coordinamento Omosessuali della Sinistra Rivoluzionaria, the network of revolutionary left homosexuals. Because of their political history that brought workers struggles into dialogue with Women’s Liberation discourses on the “sexual revolution,” this group actively fused the political practice of “gay consciousness-raising” with theories of reproductive labor and social reproduction. In the years after 1972, a new conception of autonomy emerged out of the so-called Italian workerist movement – represented by groups like Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua – to challenge reified divisions between the public and the private sphere. At that point, mass mobilization campaigns also became a distinctive characteristic of Italian feminism. These mass campaigns mobilized around the control and cost of general social reproductive needs like health, transport, leisure, and consumption, and eventually on divorce and abortion laws.

The reworking of Mario Tronti’s “social factory” thesis was crucial for this emerging strand of autonomist marxist feminism. The phrase “social factory” designates the erosion of distinctions between the workplace and society at a late stage of capitalist development as well as the transformation of the entirety of social relations into direct relations of production. The cogency of this thesis was immediately apparent to feminists, who claimed that housework and other forms of affective, sexual, and emotional labour that they engaged in was, in fact, work that capitalism structurally refuses to recognize and pay. According to the mainstream historiography of this period, feminists were the main political subjectivity that used the notion of the social factory to displace the male factory worker as the sole protagonist of the class struggle.

In 1977, the COSR began considering supplementing consciousness-raising with other political practices that help shed light on the role marginal sexual identities play in the social factory. The collective’s initial intention was to produce something of a sexual survey which might at first resemble Kinsey’s famous reports, but the epistemological horizon of this piece of research could not be any more different. The idea that workers’ accounts of their work and lives was essential to any revolutionary process goes all the way back to the questionnaire that Marx wrote in 1880, originally intended for dissemination among French factory workers. Straight autonomist organisations like Potere Operaio and Lotta Continua followed on from Marx’s model and began conducting inchieste on the lives of Italian factory workers.

For a couple of months, the collective of revolutionary left homosexuals showed up with clipboards at cruising grounds, underground bars, and public toilets to start a mutual conversation with gay men in public sex spaces about the lives of both interviewers and interviewees. By conducting an inchiesta that substitutes the factory with cruising grounds, the collective was implicitly suggesting that the affective and emotional labor of becoming a homosexual by means of underground sexual practices is one instance of reproductive labor that needs to be considered for an understanding of the transformations of late capitalism. In other words, the inchiesta placed both public sex spaces and minority sexual identities in capital’s total circuit of reproduction, and therefore within the social factory.

Fiat Lingotto, Roof test track, Turino, 1913-26, Courtesy of Archivio e Centro Storico Fiat.

Serena Bassi is an Associate Research Scholar at the Yale Translation Initiative in the MacMillan Center and Lecturer in Italian Language and Literature.