Palestinian thobes – Reflection on environments

Contributor

Mimesis

Let me see your clothes and I’ll tell you who you are—this couldn’t be more true than in the case of Palestinian thobes. Often reduced to its aesthetic and historic value, a traditional Palestinian thobe was a tool of ordinary women to reflect their existence and relationship in/with their environment.

The origin of Palestinian thobes remains vague. The fragile nature of the material and the practice of recycling dresses made it impossible to collect thobes of previous centuries; however, experts believe it to be rooted in the times of the Phoenicians and Canaan in ancient Palestine. Its current syntax with main elements like tiling is most probably the result of the Islamization of Palestine and introduction of Arab-Islamic art to the region.

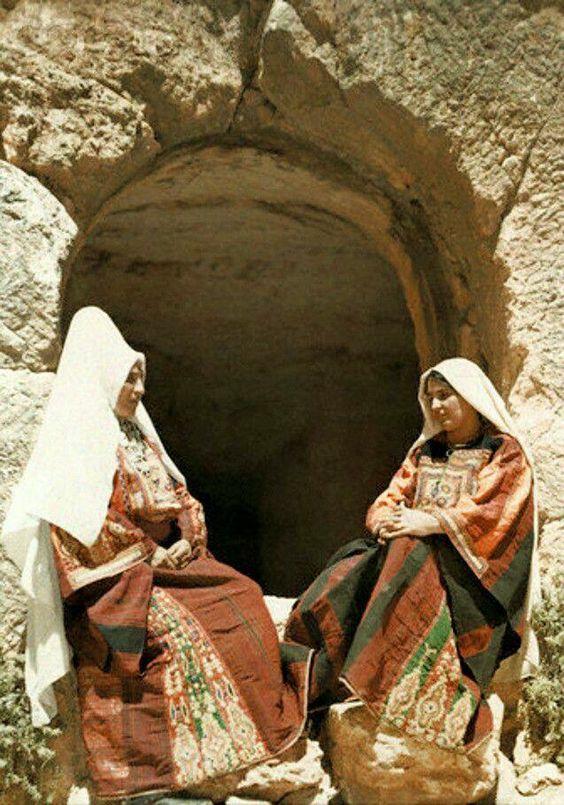

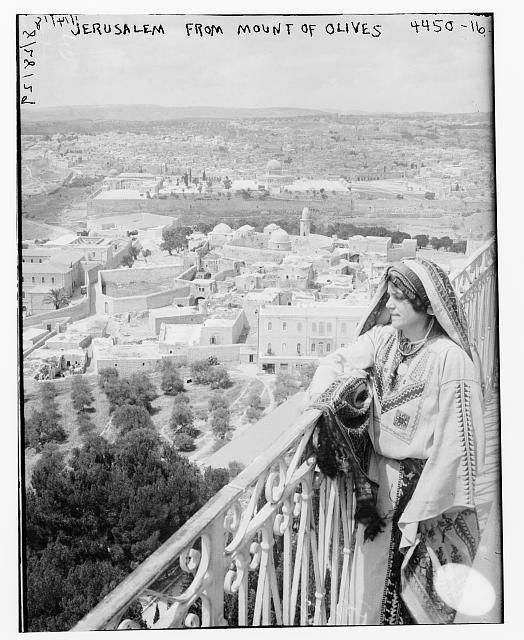

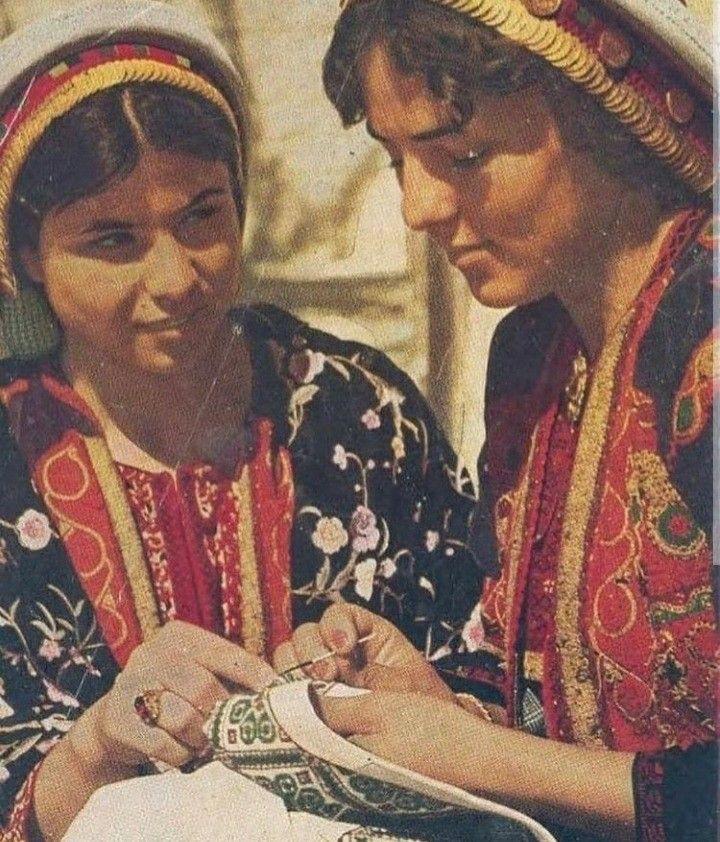

Even though the origin of embroidery in West Asia was mostly practical, Palestinian thobes stand out because of their prominent artistic value rather than for their functionality. In pre-colonized Palestine, women were mainly taking care of domestic tasks, which left them with time to work on these dresses as an activity of leisure and contemplation. Reflecting both on nature and their own existence, the authors would usually choose between different socially coded colors and motifs, creating unique dresses both for festival occasions and for everyday use, inseparable from the woman’s origin, social status, and skill level. For instance, a woman of Beersheba would prefer to use the Nafnaf—a local dessert flower—rather than a cypress tree as a central motif, stitching it in blue if she is single or widowed, or yellow against the bad eye.

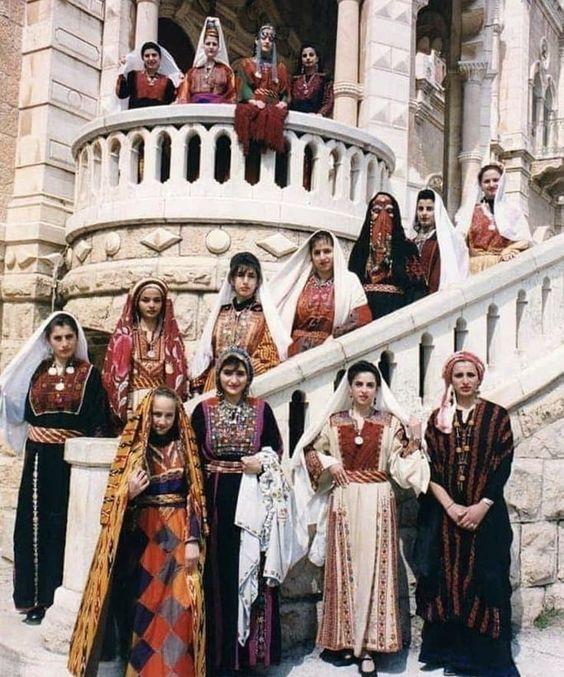

Nevertheless, the Palestinian thobe can be understood as more than just the woman’s ID card; it’s a testimony of Palestine’s history. Motifs were also adaptations of other cultures passing through Palestine in form of empires or even just products. The Byzantine architecture in Palestine, for instance, inspired locals as much as a Persian rug in the busy streets of Jerusalem would do. Beyond, the variations in design between every village were due to the remoteness of their location in Palestine with only a few exchanges between them. This changed in 1948 with the ethnic cleansing of Palestine and the expulsion of indigenous Palestinians from their land. In refugee camps across neighboring Lebanon, Syria, and Jordan, Palestinian women would share not only their pain over their lost homeland but also their art through which they stayed connected. A new Palestinian dress was created through the interchange of different motifs from a variety of Palestinian thobes.

Motif and design of the new Palestinian dress are, as a result, no longer rooted in a particular region but rather in a collective memory of pre-1948 Palestine, expressed as a political statement. These spaces of creation became a place of exchanging local culture, traditions, and stories. Its outcome was a new Palestinian dress that would allow for an expression of resistance through art—and a symbol of historic connection to their indigenous land.

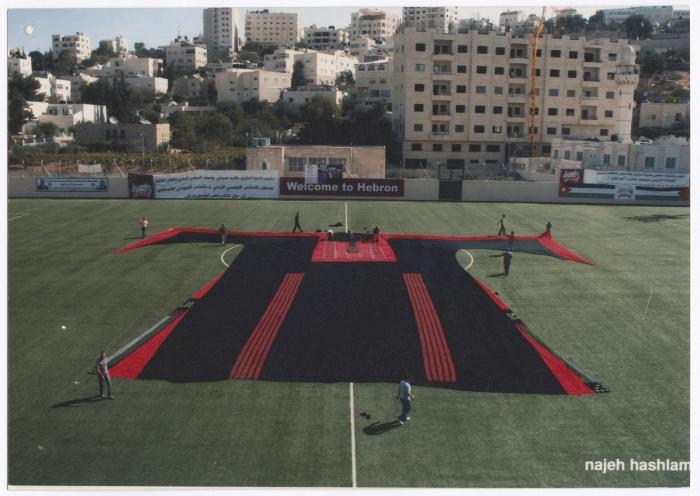

The intellectual and political dimension of the Palestinian thobe is best visible in the “intifada dresses,” referencing the first intifada. The Arab word intifada translates to “shaking of” and was a popular uprising of Palestinians against the brutal Israeli occupation that remains in place to this very day. During these protests, women would radically transform motifs of their dresses and include symbols of Palestinian resistance, such as the map of historic Palestine, reflecting political aspirations and solidarity.

Today in occupied Palestine, the traditional thobe is produced industrially outside of the country and is less common for daily usage. Instead, its standing as a piece of national pride remains stronger than ever. In everyday life, one always encounters the figure of Mother Palestine, an elderly woman in a Palestinian thobe, in children books or commercial ads. But also in high culture, like in the art of Jordan Nasser, the tatreez (Stitching) of the thobe is used in the diaspora as means to reconnect with Palestine.

The design of the Palestinian thobe changed over the last hundred years quite a lot; however, its intellectual backbone is still present. It is a medium that represents the natural connection between the indigenous people of Palestine and their land. It is a canvas for artistic self-realization and political aspiration. It is a piece in the social weaving of Palestinian society and a symbol capable of representing collectivity and individualism at the same time. The Palestinian thobe is an example of how we can navigate through binary ideas of universalism and individualism, internationality and nationality, and even nature and culture. If a woman used nature to produce culture and Jordan Nasser used culture to place himself in nature, we can conclude that there is no divide between nature and culture but rather that everything is mutually interconnected.