Counterfeit Realism

Contributor

Magical Realism

Recently ‘Bob McNeel’ sent an email blast inviting us to try “The new Rhino 7 WIP render engine [which] improves realism.”With so many of us seduced by realism, it may be challenging to disentangle the discrepancies between our digital models and the physical environment. Meanwhile, the transaction between the digital model and applied graphic (texture map) is left unchallenged by the discipline due to the value they add to the rendered image, perpetuating the conceit that photorealism is real.

While flatness and surface may often be viewed as synonymous terms within the architectural context, consider them within the broader cultural terms of literalism and realism. Literalism is the reading of something fighting against interpretation - a “this is this” mindset. Whereas in contrast, realism is decidedly more ambiguous - an experienced condition that reveals the mechanism present in something’s performance. For example, consider the process of photogrammetry and its uncanny ability to generate seemingly real 3-dimensional duplicates from 2-dimensional source images. The resulting method provides a wire-frame, point-cloud, and a separate image file, not too dissimilar from a taxidermied animal. Problematically, the software is content-agnostic, so regardless of the input’s quality, it will self-heal into a fully realized blob. Whether it be Google Earth or Oliver Laric’s Lincoln 3D Scans, it may be surprising that I would consider these photogrammetric blobs to be examples of realism, as the digital texture map could not be further away from the real, nor the experienced reality of encountering the original source. These models are real not because they are visually real, but because the data points are real. However, these digitally rendered masses exemplify the deceit present when contemporary architecture pushes the discipline to become increasingly more picturesque.

Perhaps the earliest example of faux realism – helping differentiate surface performance and the texture map – is the statue of Augustus Primaporta from 20 BCE. In 2004, with the help of ultraviolet scanning, a polychrome recreation of the statue was created, confirming its original vibrant painted colors. Of course, faux realism (texture mapping) is not just a deception architects subscribe to, but one that other disciplines do as well. For example, let’s examine one of the graphic surface’s closest allies, the woodie station wagon, a simulated wood grain texture applied to the side panels of a car popularized in the 1960s. Here the wooden texture is literalized through a stylized imitation of wood made possible by sheet-vinyl appliques and hydrographics. Although the discipline may initially dismiss such incongruities between the texture map and its material composition, these characters confront the gap between the computationally described object and the digitally constructed surface. That said, literalism - somewhat ironically - prevents realism from deceiving so much.

There are numerous ways in which we key into faux realism. In automotive design, it is identifying irregularities across the body of the car’s surface, whereas, in architectural modeling, it may be distinguishing the seam or match line of a repeated texture map. These significant moments of interface are critical in understanding and evaluating the digital’s capacity to engage with material composition, directing the discourse toward the expanding list of tools and fabrication methods we utilize and external disciplines with which we engage.

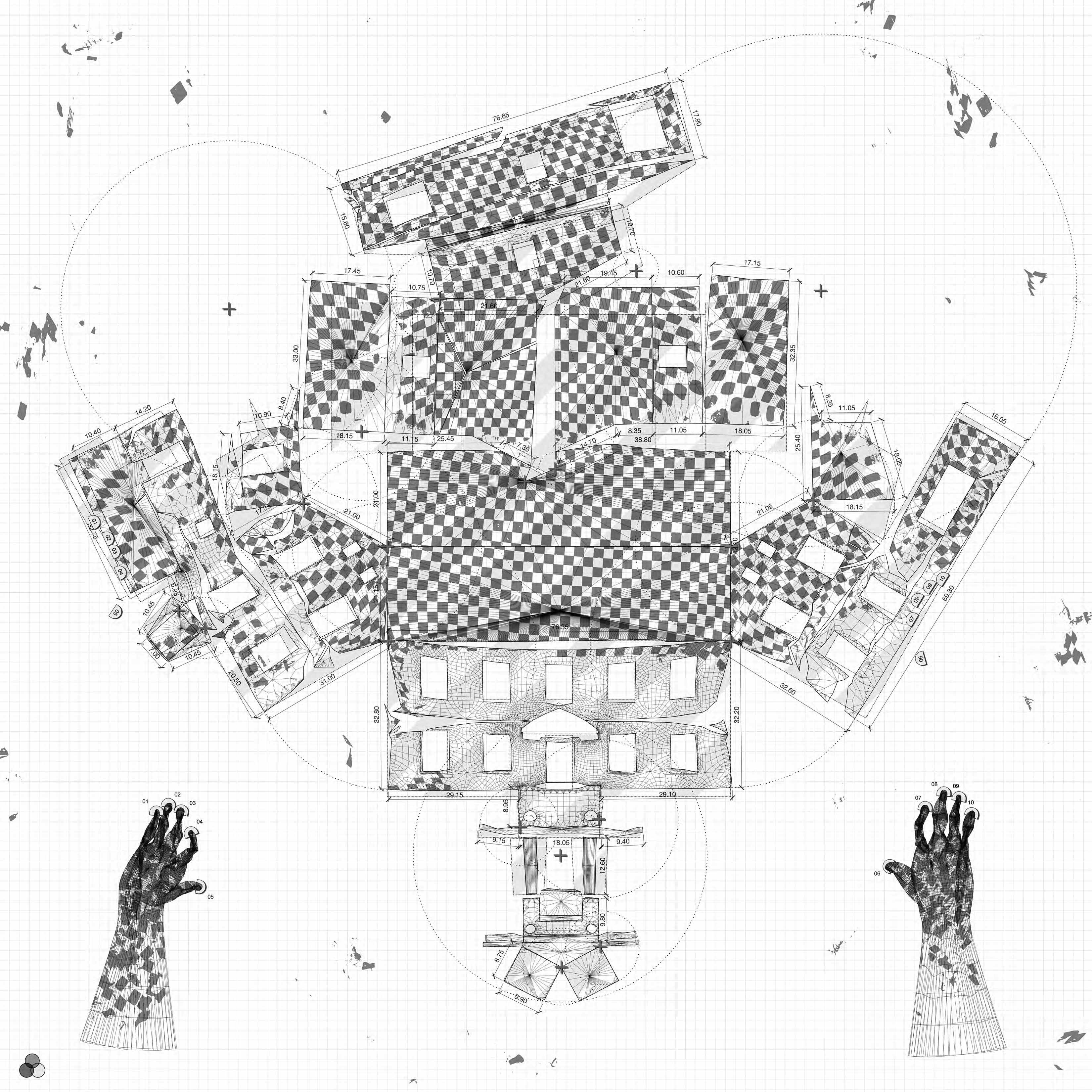

In this sense, consider soliciting help from the aftermarket automotive process of hydrodipping to apply a green-checkered pattern onto the surface of a deflated 3D printed house. In an instant, everything submerged into the hydrographic bath becomes tattooed with the same checkered pattern, which clings to everything. Emerging from the water’s surface along with the checkered house are the hydrodipper’s hands, which are tattooed with the same pattern, intersecting the moments between material composition, application, and fabrication method. Smuggled into this exchange, perhaps unwittingly, are also the aftermarket automotive industry’s values and the realization that we have a shared interest in advancing surface articulation. The hydrodipper’s hands intersect the moments between material composition, application, and fabrication method with the newly tattooed graphic illustrating the principle of literalism. Perhaps the aftermarket automotive industry can provide the opportunity to elevate the discussion of surface and perception, moving us into a broader range of representational techniques to formalize ideas into a physical environment by transforming a documentary tool historically used to perpetuate deception and reconstruct it as a generative agent.

Fig 1: Unrolled developed surface drawing of: hydrodipped house, loose floaters within the bath, and the hydrodipper’s hands