The Compound & the Commons

Contributor

Life After Love

M.Arch I 2016, lives in New York, where he edits The New York Review of Architecture and is not yet sure his baby understands that interdependence is a two way street.

This piece is in response to a letter published in PAPRIKA! Volume 3, No. 16 titled “Fuck Your Hallway.” 1

The first thing that comes to mind today when I think about Rudolph Hall? The end of the world. More specifically, “preppers.”

In a September op-ed for The New York Times, journalist Mira Ptacin catalogued two types of preppers. 2 The first group plays to its stereotype: those, mainly white men, who are convinced that society will collapse within their lifetime, and who prepare for such an event by stowing food, supplies, guns and ammunition in safe rooms and remote hideaways. When ‘the big one’ (The End Of The World As We Know It) arrives, they will hightail it to their bunkers, ready to weather the storm. I call them the independent preppers. Ptacin’s second kind of prepper also believes in calamity and our vulnerability in times of crisis, but instead of preparing to sever their ties to others, these preppers instead work on deepening them. They see preparedness not as a lonely, self-reliant pursuit, but rather as a communal one. I call them interdependent preppers. When the storm strikes, they worry not just about having enough food for themselves, but also for their neighbors. They believe we survive crises together, or not at all.

Rebecca Onion, in a June book review for Slate, documented sub-genres of apocalypse fiction that illustrate the two types.3 In James Wesley Rawles’s “Patriots: A Novel of Survival in the Coming Collapse”, the protagonists are independent preppers who are perfectly in control, executing an elaborate plan (as well as most of their enemies) as the world spins out of control around them. By contrast, in Emily St. John Mandel’s pandemic novel “Station 11” the protagonists are interdependent. They don’t have a plan, but they adapt quickly, show empathy, find lots of friends, and build communities that pull society back together.

These two types of preppers have architectural analogues: the compound and the commons. The independent prepper builds the compound, secure against a hostile world. The interdependent prepper builds the commons, marshaling the resources of many. Access sets them apart: a compound controls access, the commons does not. The compound relies on walls for passive coercion. A community bound by norms guarantees the porosity of the commons.

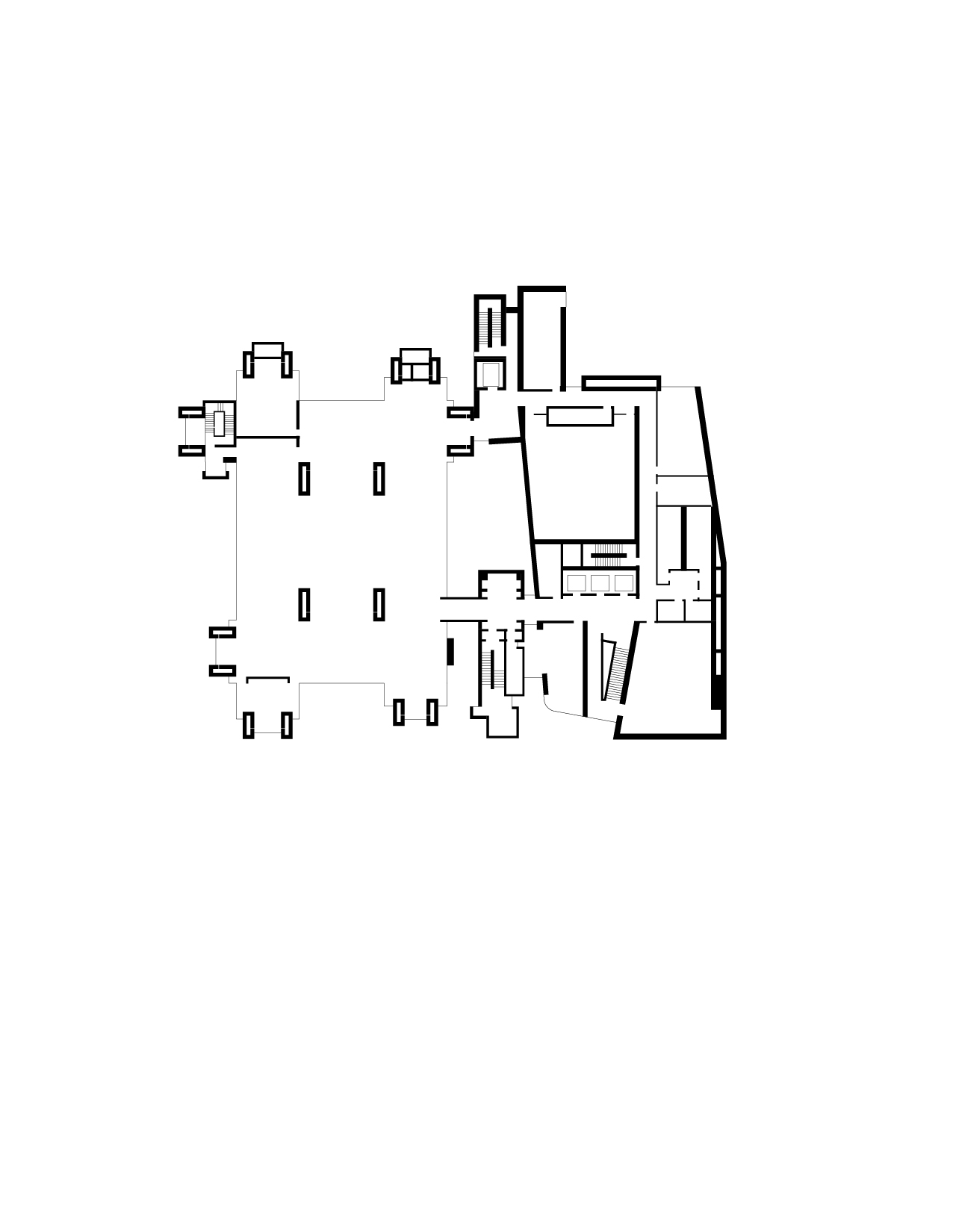

For the students and faculty of Yale’s architecture program, Rudolph Hall is a commons. Its spacious and interlocking open studios wrap around open pits, which variously serve as presentation space, classrooms, and badminton courts. Everyone is visible – and audible – leading to deep interdependencies. If a student struggles, help is nearby. Ebullience and enthusiasm prove infectious. This is not always so in academic environments. As I noted a few years ago in a piece for Paprika!, Rudolph’s sibling in the art history department, Loria Hall, is closer to the academic norm: all hallways and closed doors. A friend of mine – studying for his PhD in Italian literature – once walked onto the studio floor and exclaimed to me, ‘This is some sort of academic heaven!’ His program, too, lived in a warren of offices and nooks with closed doors.

That said, the interdependencies of the commons are double edged. Unless a community as a whole is intentional and vigilant, the commons leaves individuals with little protection against oppressive norms - therefore the wisdom of safe spaces for marginalized groups. In the case of studio, hyper visibility also leaves students exposed to high pressure and toxic competition. On a less abstract level, our nation’s inability to control the novel coronavirus this year left many of us with retreat to compounds, small and large, as our only recourse for our health. Nevertheless, we have interdependent preppers and their work in the commons, not the walls of our compounds, to thank for our survival so far in this catastrophic year. Whether it was delivering the garbage, driving a bus, growing food, checking in on neighbors, or charging into hospitals with high viral loads and low amounts of PPE, people stepped up, engaged, and kept society intact. Had we all been independent preppers, had everyone fled New York, that would have been the end of the city. This is the peril of compounds, and the prepper paradox: if, in a time of crisis, everyone flees to take up arms against everyone, then predictions of collapse prove self-fulfilling.

A building can be both a commons and a compound, depending on one’s perspective. A single-family home is, vis-à-vis the rest of society, the ultimate compound, but within its walls it can be an extraordinary commons, a space of interdependence without limit. Rudolph Hall may be a commons for its community, but vis-à-vis the city of New Haven, Rudolph Hall is without a doubt a compound, complete with towers, parapets and blank concrete walls. These walls will always provide easy encouragement to instincts of isolation and a stumbling block for the many deep and ongoing efforts of its community to engage with its city.

If Yale’s architects are to join the interdependent preppers, working to strengthen society against the formidable challenges to come, Rudolph Hall needs to find a way to puncture its bunker and establish some common ground with New Haven. The coronavirus has shown us how unnecessary many of our walls have been, as we take previously private dinners, parties and performances and host them all on streets and parks. As our buildings become again habitable, maybe Rudolph Hall could part ways with a few walls for good.