On the NHS: Selling the Family Silver

Contributor

Just What the Doctor Ordered: Health and Architecture

_“All told, around two million hectares of public land have been privatized during the past four decades. This amounts to an eye-watering ten percent of the entire British land mass.”_¹

Over £400 billion worth of land once owned by Britain’s government agencies has been sold to private developers since Margaret Thatcher took office in 1979.² Contrary to public perception, these land sales have persisted under successive Conservative and Labour governments which have prioritized short-term transactions that offer private investors high returns on rising land values, over the provision of essential public services.

The decimation of the National Health Service (NHS) Estate is documented in the Five Year Forward View (2014) and the Naylor Review (2017), which both describe the consolidation of primary and secondary care services into “mega practices” that vindicate the closure and downgrading of hundreds of hospitals and general practice (GP) family surgeries across the country. In an effort to improve “land efficiency,” the NHS is currently seeking buyers for 718 plots deemed “surplus to requirements.”³ This “commercial approach” to land disposal aims to raise £5.7 billion to help cash-strapped NHS Trusts, who have had annual budget rises restricted to one percent since 2010.⁴ Ministers have optimistically approved these selloffs in the hope that Trusts will be able to redevelop their facilities and build homes for staff.

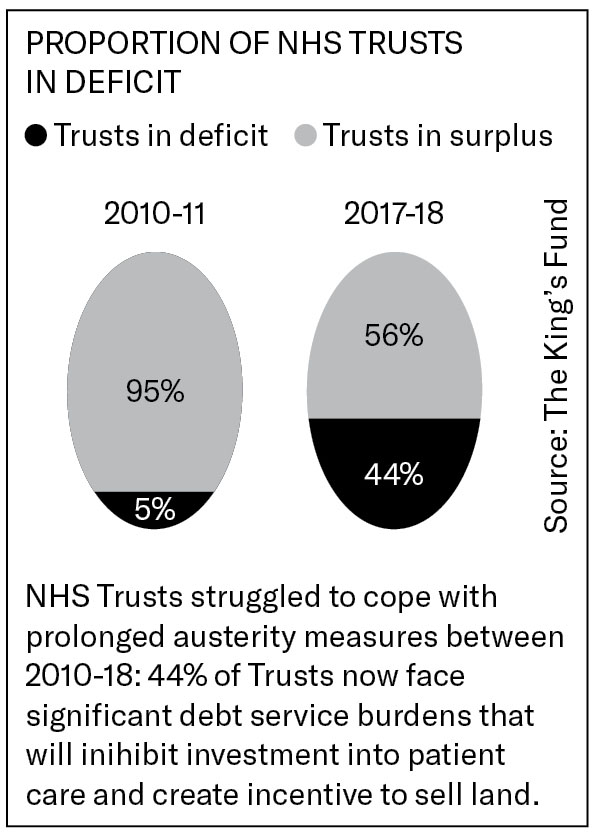

Skeptics suggest that these land sales will primarily account for the £1.2 billion NHS deficit and £3.7 billion hospital overspending bill which has ballooned during a decade of austerity measures.⁵ Dr. Nagpaul, chair of the British Medical Association, believes that “it is vital to safeguard the sale of NHS land from perverse short-term financial incentives… and a reduction in facilities that is insufficient to meet the future needs of patients.”⁶ The sale of the NHS’s “family silver” has attracted widespread criticism from healthcare professionals and opposing Members of Parliament who believe that hospitals will have little room to expand in the future. Under the government’s current plans, Charing Cross Hospital will shrink to just 13 percent of its current area, with its accident and emergency rooms, intensive care, and emergency services to be distributed across the city.⁷ Similar strategies will significantly diminish other flagship London care centers, including Chelsea and Westminster Hospital and the historic eye

hospital, Moorfields.⁸

But if the sale of the NHS Estate fails to operate in the best interests of hospital trusts, clinicians, or patients, then who stands to gain from these transactions?

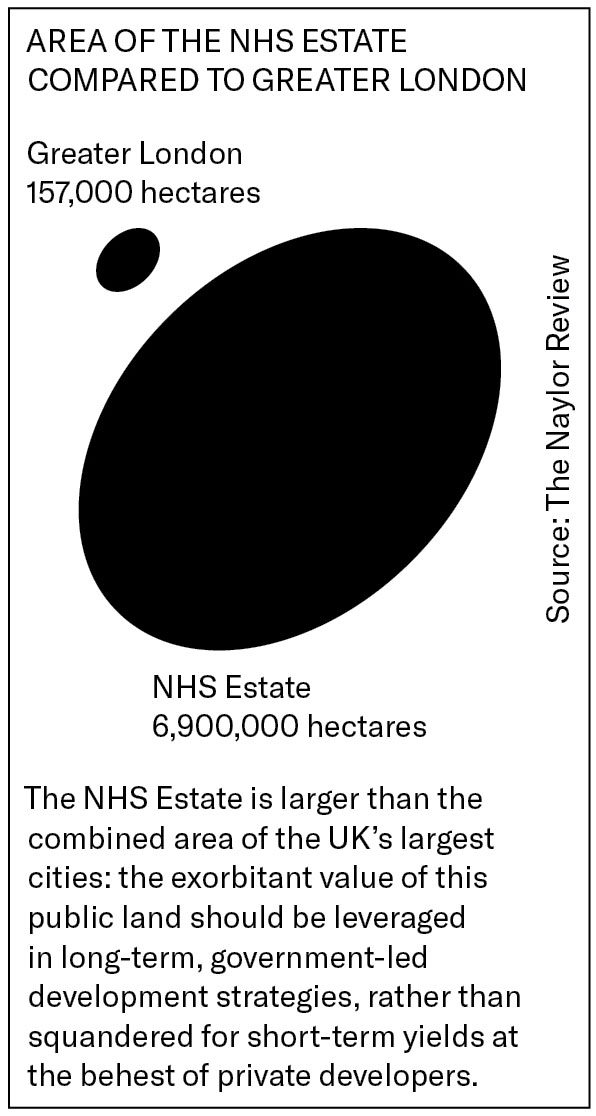

As stated in the Naylor Review, the NHS has neither an overarching strategy nor in-house technical skills to manage an estate 10 times the area of Greater London.⁹ The government’s ambition is to transfer the difficulties of owning and managing a colossal real estate portfolio to the country’s largest developers, in the hope that they will develop plots into affordable housing. With NHS Trusts unable to finance public housing development on their own land, the true beneficiaries of these land sales are institutional developers who can retain the long-term yield from their projects.

By selling an abundant NHS Estate procured over the past century, the government gives private businesses significant leverage over not just public land, but also the provision of healthcare itself. Whereas profits from the NHS Estate would traditionally fund care services, private companies are profiting from the government’s willingness to part with valuable land. One such organization rising from the ashes of public service is Project Phoenix, a public-private partnership (PPP) between NHS Trusts and regional asset management firms that organize land sales with large developers who siphon profits from the Estate away from the public purse. Once the public land is sold, NHS Trusts must then pay to rent land that it currently owns and operates: these cripplingly expensive leases

push already inundated Trusts further into deficit.

Similar Private Finance Initiatives (PFI) have extended beyond land procurement and into building maintenance. St. Bartholomew’s Hospital in London is now tied to a 35-year PFI contract to renovate and extend existing facilities which will cost £6.85 billion in loan interest alone.¹⁰ Ministers have insisted that PFIs ensure the risk of hospital construction and maintenance is borne by the private sector, where building delivery is also assumed to be more efficient. However, 35 percent of healthcare PFI projects have run over budget and have typically failed to insulate the public sector from hospital construction risks: the collapse of construction monolith, Carillion, forced Royal Liverpool and Birmingham Midlands Hospitals back into public administration, with the taxpayer assuming a record £7 billion liquidation bill, and leaving facilities unfinished.¹¹ The evidence abounds for the detrimental effect that PFIs and private land sales have had on the NHS’s ability to deliver suitable healthcare centers and attend to patients on time.

The British public is ominously witnessing the structural and financial degradation of its most treasured public institution: in the process, funding for core NHS healthcare services is becoming embroiled in the fluctuations of private real estate markets and weaved into the narrative of the housing crisis unremedied by the country’s largest developers. Instead of ransacking the NHS Estate to give the private sector leverage over public services, the government should develop land it already owns and redirect profits into emerging technologies and facilities that build a resilient, twenty-first century healthcare system. If the government endorses such public development vehicles, by raising Trusts’ borrowing caps and retaining land to expand facilities, design and construction industry professionals could take a leading role in delivering hybrid models of healthcare and housing that meets the needs of patients and investors, without devastating the public purse.

[1] Brett Christophers, “The Biggest Privatisation you’ve never heard of: land,” The Guardian, February 8, 2018, http://bit.ly/2GcjezY

[2] Ibid.

[3] Robert Naylor, “NHS Property and Estates: Why the estate matters for patients,” UK Government, March 31, 2017; Ibid.

[4] Denis Campbell, “NHS land earmarked for sale soars,” The Guardian, September 9, 2018, http://bit.ly/2DWktRI

[5] Henry Bodkin, “True scale of NHS overspending eye-watering,” The Telegraph, August 31, 2017, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/08/31/true-scale-nhs-overspending-eye-watering-new-report-finds/

[6] Mark Gould, “NHS land sale is ‘selling off the family silver,’” On Medica, accessed 5th February 2019, https://www.onmedica.com/newsArticle.aspx?id=c348ca25-f780-4c0d-a3b4-d2b162a358a6

[7] “Report confirms plans to sell Charing Cross,”Neighbournet, accessed 5th February 2019, http://neighbournet.com/server/common/hfnhsclosures087.htm

[8] Ben Clover, “The four sites which could earn the NHS £4bn,” Health Service Journal, April 27, 2017, https://www.hsj.co.uk/hsj-local–north-east/the-four-sites-whose-sale-could-earn-the-nhs-4bn/7017581.article

[9] Nigel Edwards, “NHS buildings: obstacle or opportunity?” The King’s Fund, July 13, 2014, https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/field/field\_publication\_file/perspectives-estates-nhs-property-nigel-edwards-jul13.pdf

[10] “PFI and the NHS,” Patients4NHS, accessed 5th February 2019, http://www.patients4nhs.org.uk/pfi-and-the-nhs

[11] Jonny Ball, “The policy behind Liverpool’s empty hospital,” New Statesman, October 16, 2018, https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/healthcare/2018/10/policy-behind-liverpool-s-empty-hospital