Fuck Your Hallway

Fuck That

The Loria Center is an utterly useful building. Rudolph Hall would never get on without it. The elevators are in Loria, the heating and cooling ducts are in Loria, the fire escapes are in Loria, even the toilets are in Loria. That is right: you cannot so much as take a dump without going into Loria.

For all that work, Loria—Rudolph’s neighbor to the east—somehow manages not so much as to block the eastern view from Rudolph. It goes to great pains to be shorter than Rudolph Hall. Like a stooping servant, it disappears precisely along the sight lines from Rudolph Hall’s penthouse.

Rudolph Hall, opened in 1963, takes its name from its architect and client, then dean of the architecture school, Paul Rudolph. It is his masterpiece, and it houses the faculty, undergraduates, Masters, and PhDs of Yale’s architecture department. The Jeffrey Loria Center of Art, designed by Charles Gwathmey, ARC ’62, and opened in 2008, houses the faculty and PhDs of the Art History Department, and hosts classes and lectures for the rest of the university.

Paul Rudolph anticipated his opus’s progeny from the beginning, leaving space and connection points for an envisioned college quad. Yet Rudolph’s proclivity for theatricality—the twenty-seven level changes, the never regular stairs, the cliff-like dropoffs, the almost complete lack of private space, the ceilings high and low—left Loria burdened, as it were, by a capricious grandparent. Exhausted, perhaps, by the abuse of its dependent, we can understand, though not forgive, Loria for in turn abusing its own family, that is, the art history department.

Loria pretends to be edgy, the cool parent. It jags at the bottom, swoops at the top, and sports a window that juts like a pierced lip over the entrance, à la Breuer’s Whitney Museum in New York.

This pep, however, evaporates on the interior, where the rooms and corridors are so identical that without signage it is impossible to know your floor.

The envelope takes its cues not from Breuer, but from a servile allegiance to technology, such as projectors. Art history, apparently, can only be taught with projectors, which in 2008 needed dark rooms to function. The technology of course improved: projectors work just fine now in bright rooms. But almost all of the classrooms are stuck with tiny windows, and the two lecture halls are sealed vaults. Then there is sustainability: to earn its LEED gold certification and deliver 22 degrees Celsius, Loria seals its inhabitants—and in fact those of Rudolph, too—in a climate controlled thermos with almost no operable windows. While ideas in sustainability have since shifted, emphasizing now thermal variety and maximizing contact with nature, the art history and architecture departments are still stuck in a thermos.

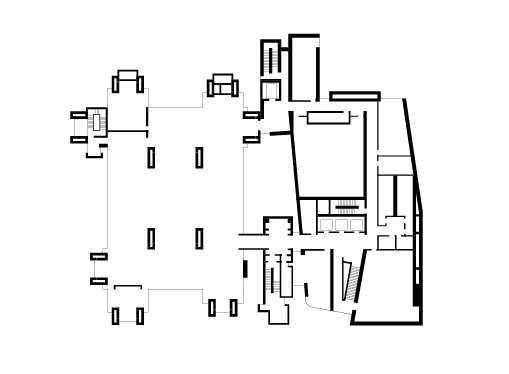

Loria’s plan, however, is the real crime: on each floor, a single hallway threads its way between narrow, shotgun like offices, seminars and lecture rooms. All of the rooms are absolutely discrete and without overlap. There is never a reason to be in a room unless you are using that room. Even the occasional internal window feels awkward. The parts never combine to make a whole larger than themselves. They never combine to make a whole even as large as their parts.

The main entrance—the elevator lobby—through which hundreds pass each day—is kept empty of furniture. Its natural inhabitant, the cafe, is literally cut away, a cramped nub shorn off to keep it out of the way. Loria’s plan is akin to that of a gated community, a suburban subdivision, each house keen on privacy and afraid of its neighbors. There are even cul-de-sacs on the upper floors. The only person whom everyone gets to meet—the only person who gets to spend time in a shared space—is the guard (Gloria, a truly wonderful soul).

Certainly Loria’s architect, Gwathmey, meant no harm. He was only trying to give his clients what they wanted. The architecture department wanted the Rudolph Hall from the 60s restored, wanted their views to remain unimpeded, and wanted the toilets elsewhere. Gwathmey delivered, brilliantly.

What did the art history department want? They probably had a list: offices, classrooms, LEED gold certification, etc., and then—in a moment of conflict, seized by some dark spirit—insisted that each of these things should stand by itself. Like a genie fallen into the wrong hands, Gwathmey again delivered, composing a rabbit warren, a department best described as fragmented, balkanized, and silo-ed. He dutifully killed the best chance the art history department would ever have of gaining a building that could nurture community.

This dark spirit, nurtured no doubt by the nest it ordered, still stalks the hallways of Loria today: look no further than the one saving moment of Loria, the gigantic terrace with sweeping views of the city. The door is always kept locked.

Rudolph Hall’s plan, by contrast, features almost no hallways. All horizontal circulation happens through the open center, the pits, which then act as natural public squares. Every time anything happens in any part of the building, the energy compounds across the pit. Rudolph’s plan is a masterfully composed doughnut, the glowing soul of the architecture community cradled within. And Loria’s? A noose.