Out of the Woods?

Food

01.21.2016

YANBO LI (B.A. ’16)

Last July I spent three nights at D Acres the New Hampshire Permaculture Farm and Agricultural Homestead. My friend and I were in the area for its rock climbing. We had been enticed to the farm by its cheap lodging and yoga room, and the inherent promises of novelty, or at least quirkiness. We checked in during the middle of the night (“Yeah don’t worry; it won’t be locked.”) and hence did not meet any permanent residents until the following morning. As we stepped down the stairs like a pair of children in a big hippie castle, we were met by a white man in his late forties with salt and pepper hair down to his shoulders, who faced us and offered, “Hi! My name’s Root.”

Hidden beneath its easy façade of a wooded rustic hippie commune, D Acres is a land-use and community experiment founded on the academically rigorous principles of permaculture. Permaculture (“permanent agriculture”) is a systematic method of design formalized by Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren in the late 1970’s. As a response to industrial agriculture, which they perceived as detrimental to biodiversity, soil fertility, and future availability of resources, Mollison and Holmgren developed a framework influenced by both pre-industrial farming methods and practices of forest gardening that had been germinating in the decades prior.

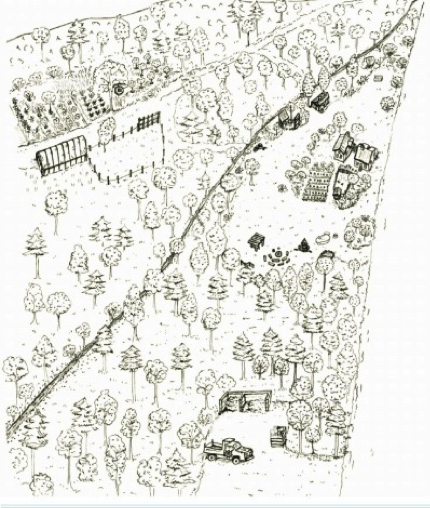

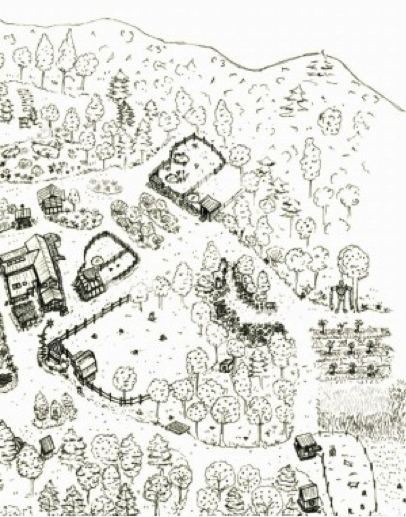

Site plans of D Acres (Courtesy of Josh Trought)

Put simply, permaculture is a way of producing food and materials by building in a way that both mimics and works with nature. It de-emphasizes human intervention in favor of a deep understanding and application of natural processes. In practice, this involves techniques like keeping a seasonal diet, cultivating many plant species in the same area, and using cardboard to imitate the role of leaves on the forest floor—stifling weeds while decomposing and returning organic matter to the soil, like recycled mulch.

The residents at D Acres—including a YC Class of 2011 Yale alumna—walked us through forested trails to treehouse residences, berry shrubs, and vegetable patches. Their pigs had been let out into one of the fields so that they could rout through the soil and kitchen scraps dumped there, simultaneously feeding the pig and mixing organic material into the earth. For meals Root made salads and stews and strawberry-herb sauces and even homemade mayonnaise, using ingredients either from their own land or which “could reasonably be grown” in rural New England. The toilets were placed atop long chutes leading to a basement collector for “humanure” and flushed with a bowl of sawdust. They offered us the option of waking up at five in the morning to watch them wrangle some pigs. We declined. If these were hippies or hipsters, we had the sense that they dropped less acid than the ones in the seventies and did more physical labor than the ones in New Haven.

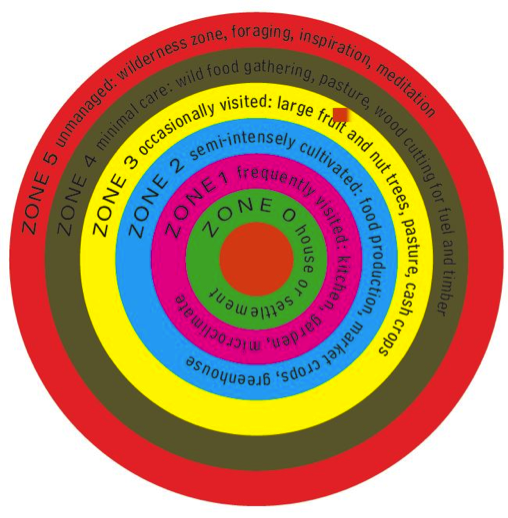

The way that D Acres founder Josh Trought has set up the principles of life on the homestead reverberates through the way they have shaped the space around them. In addition to the compost toilets, D Acres has its own electrical and heating infrastructures, featuring solar water heaters and wood-burning stoves. But the home itself is only a small component of the space used for living. In the permaculture categorization of human environments, it is Zone 0. Zones 1 through 4 are cultivated lands, ranging from heavily managed salad crops and compost bins in Zone 1 to the semi-wild foraging that occurs in Zone 4. Zone 5 is pure wilderness, reserved for the observation of natural patterns and the enriching buildup of bacteria, molds, and insects. Though some zones are more frequently touched than others, all are necessary for a sustainable human ecosystem.

The Five Spatial Zones of Permaculture

Whereas so much of sustainable design today is premised on new technology and design that accommodates a consumer lifestyle, the design of D Acres above all is an illustration of an environment built and adapted around a conscientious mode of living. Successful permaculture requires that form follows philosophy, whereas in most LEED-certified buildings today, form tries to make up for a lack it.

Permaculture, then, is not only an agricultural method or a lifestyle, but an aesthetic.

In the documentary miniseries Phantom India, director Louis Malle muses that he, a modern, Western man, was “master of time, slave to time.” Life at D Acres is also enslaved by time, but not to a kind of time that can be mastered. The rhythm of life is chained not to hours and weeks, but to the chill of early morning and to winter’s long, pensive nights. The aesthetic of permaculture embraces that which is slow, that which, like a forest, builds complexity over seasons and years through the interactions of its component parts.

A pear tree is neither just a tree nor simply a food commodity; it is the shade it provides to underlying shrubs, the erosion control of its root system, and the nectar it provides to bees, among hundreds of other roles. It is nothing more or less than that specific pear tree planted there in that soil in that watershed next to those other plants.

Hence, the aesthetic of permaculture is simultaneously a resistance against reduction and abstraction. It is an aesthetic of observation and patience, of complexity and particularity. It is an aesthetic of a careful balance between human and environment.

And there, is a lesson for architects.