Making Mumbai

Contributor

Figments

During a Mumbai monsoon, everything becomes softly amorphous. The grey-blue of the indistinguishable sky-sea leaks into the land as the rain falls. The otherwise crisp summer delineations dissolve and it seems as though Mumbai, momentarily, resembles the estuary it once was.

…

Bom Bahia

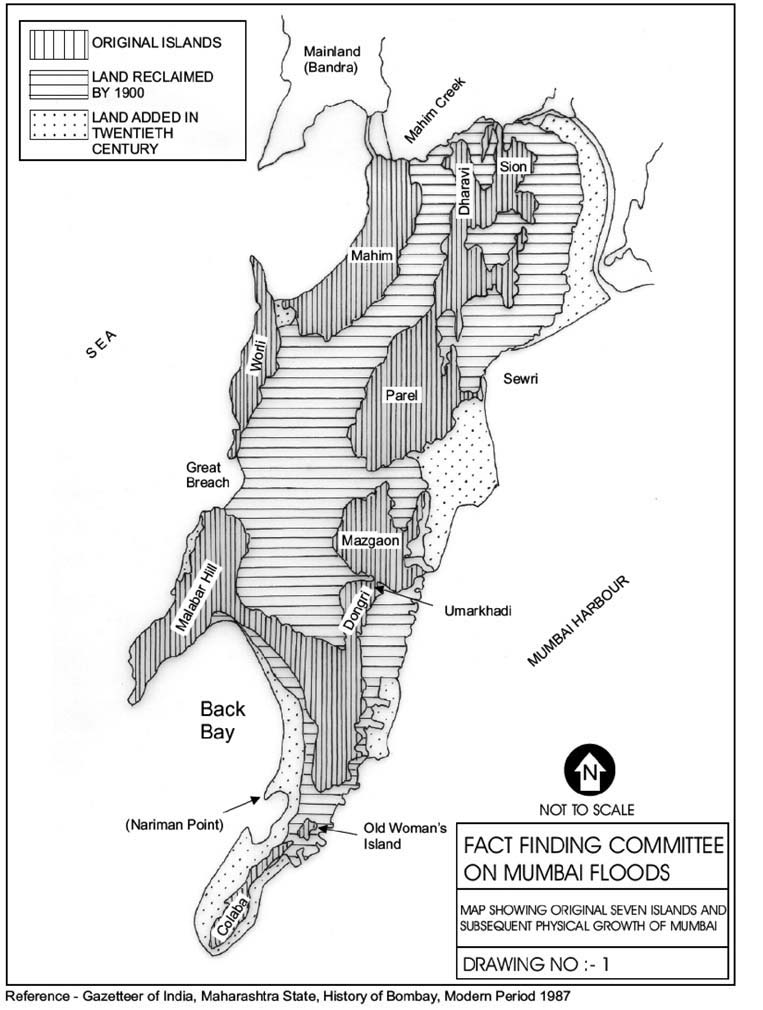

In the early 1500s, it is this estuarine ecology—composed of mudflats, marsh land, and mangroves—that the Portuguese encountered upon their arrival as it surrounded an archipelago of islands that today undergirds the city. As an estuary is known to, these islands too grew and shrank with the weather; they were so porous that while the general belief is that the archipelago was composed of seven distinct islands, early maps suggest that the Portuguese thought of it as four islands.1

Numerical discrepancies wrought by ecology aside, the Portuguese quickly took to this archipelago and it soon came to be known as Bom Bahia (‘good bay’ in Portuguese). So good was this bay in fact, that the islands were ceded to the British as a part of Catherine of Braganza’s dowry to Charles II in 1611.

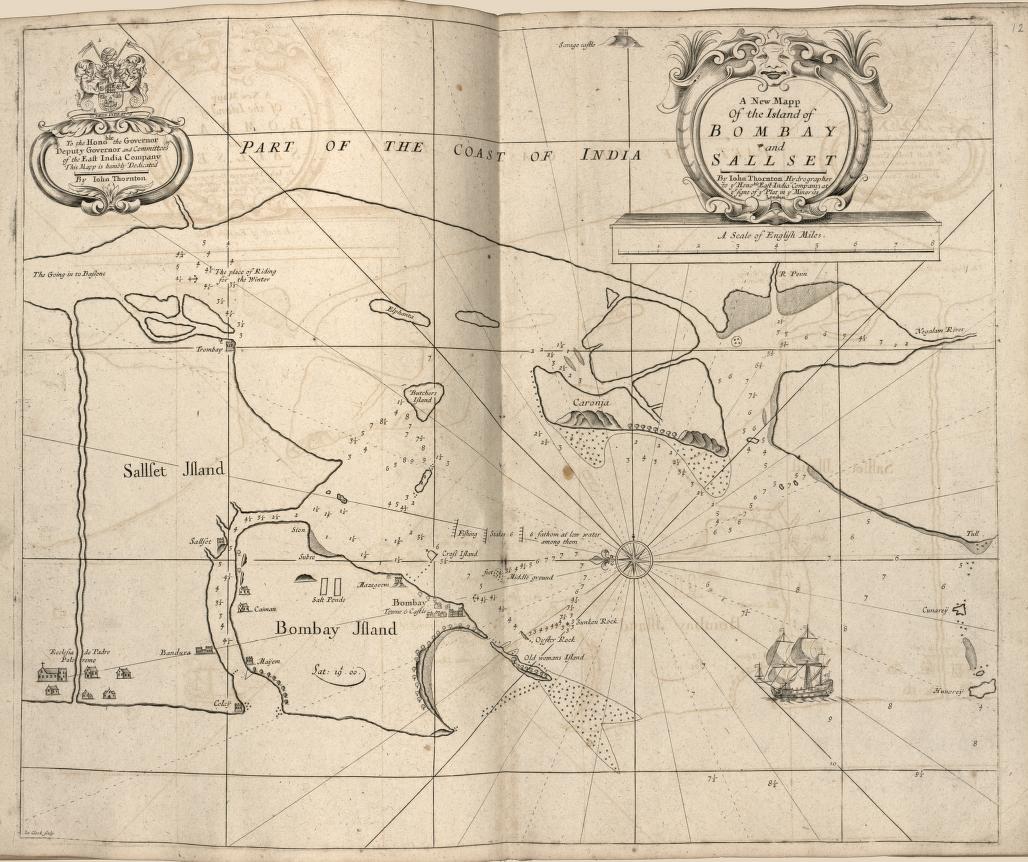

As the population of the city grew under the British and as they further developed trade, it became imperative to them to connect the islands and distinguish land clearly from sea, hence easing transport and creating more space. For instance, A New Mapp Of the Island of Bombay and Sallset created in 1700 by John Thornton for the EIC not only defined the islands’ coasts and reduced the archipelago to a single island, but also reduced the complex ecological gradients that shaded the shoreline to a simple cartographic line.

Thornton’s map was materially realized by the British beginning in the late 18th century through a series of land reclamations which by 1872 had added four million square yards to the city.2 The Portuguese quickly became a footnote to British reimagining of the islands. With these reclamations—where hilltops were cropped, and their earth used to fill up otherwise inundated areas and mudflats—the several islands of Bom Bahia were transformed into what Thornton and the British insisted was “the Island of Bombay.”

Bombay

Soon after reclamation, Bombay established itself as an important British port. It underwent multiple rounds of urban expansion as Victorian Gothic buildings—primarily used by the colonial government—began to dot the southernmost tip of the city.

In 1909 a second wave of reclamations, known as the Backbay reclamation scheme, was proposed. And just as the 18th century reclamation had heralded a new era for the city as it became indispensable to the British Empire, the Backbay reclamation scheme too pointed to a fresh reimagining of the city.

Once again, with the coast being reinvented as lines on a map and land being conjured from the sea, the new reclamation was completed in 1929. The completion of the Backbay reclamation coincided with the passing

the Purna Swaraj which declared a definite “severing of ties with the Empire and demanding complete and unconditional independence from Britain.”3

The echoes of this were made manifest in the development of the Backbay. The new residential buildings built on the reclaimed land were all built in the Art Deco style, specifically in what has been identified as “Bombay Deco,”4 which boasts of classic Deco elementsinterwoven with strands of the Indian visual tradition. Hence, the new reclamation had allowed for the flourishing of a style which was at once modern yet representative of an emerging independent India.

Even though Bombay would be officially renamed Mumbai as a part of purportedly anticolonial efforts in 1995, the Backbay reclamation had in spirit allowed the city to rechristen itself as it was wrested from British control; it was a city anew as it abandoned the Victorian Gothic style that regulated its streets and feverishly adopted Deco which better represented its emerging population.

Mumbai

While these reclamations had allowed for the city to be successively and wildly reimagined, much has been sacrificed to the maintenance of the fictions wrought by reclamation: the ecology of the coastline has been irreparably damaged, and the estuary has been hardened into wilfully definite lines of land and sea. As a result, the city unceremoniously floods annually and 6,500 concrete tetrapods weighing 2 tonnes each are placed along the coast in the hopes that the ravenous sea would eat at them instead of devouring reclaimed land.

Despite the widely known perils associated with land reclamation, especially at the apogee of climate change, in 2012 the Indian government decided to reclaim even more land. This new reclamation, which began in 2018, will allegedly be devoted to the Coastal Road which has been hailed as a beacon of progress and epitome of infrastructure in Mumbai.

This latest round of reclamation too serves to reimagine the city as it is part of a larger constellation of 21st century development projects that strive to exaggeratedly display India’s self-assertive modernity. This modernity, however, is only made tangible in the form of invasive infrastructure and roads as India begins to position itself as the type of country it hopes to be in the future.

…

If the British tried to remake Bombay in service of their imperial interests, first by separating land from water, and subsequently, by consistently reclaiming land, then the measure of their success is the degree to which the city is still infatuated with this reigning obsession with stark divisions and primacy of estate over estuary.

A New Map Of the Island of Bombay and Sallset by John Thornto,n1700.

Library of Congress,https://www.loc.gov/item/2010592349/.

The Mumbai city district showing the original seven islands and subsequent physical growth of Mumbai, 1987 Gazetteer of India

- Tim Riding, “‘Making Bombay Island’: land reclamation and geographical conceptions of Bombay, 1661-1728,” Journal of Historical Geography59, (2018): 28. ↩︎

- Gyan Prakash, Mumbai Fables, (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2010), 44. ↩︎

-

Chirayu Baral, “Dreaming of India- how Bombay used Art Deco to discover a new rendition of a nascent India,”Art Deco Mumbai Trust, Feb 12, 2019,

https://www.artdecomumbai.com/research/dreaming-of-india-how-bombay-used-art-deco-to-discover-a-new-rendition of-a-nascent-india/ ↩︎ - Ibid. ↩︎