SUPA DUPA BUBBLENESS

Contributor

Fashion

ON ENVIRONMENTAL MEDIATION AND MAKING SOME MOTHAFCKING SPACE

IN 1970 the Oakland Tribune reported on a plastic air container that had overtaken the lower Sproul Plaza at the University of California, Berkeley.

An air failure has occurred!

Those who cannot escape the pollution will die within 15 minutes!

15 minutes!

But wait—the Clean Air Pod 1500 will provide shelter!

Just sign a waiver to enter, the CAP 1500 will filter out all deadly pollutants!

Those unwilling to do so will be declared dead in 15 minutes!

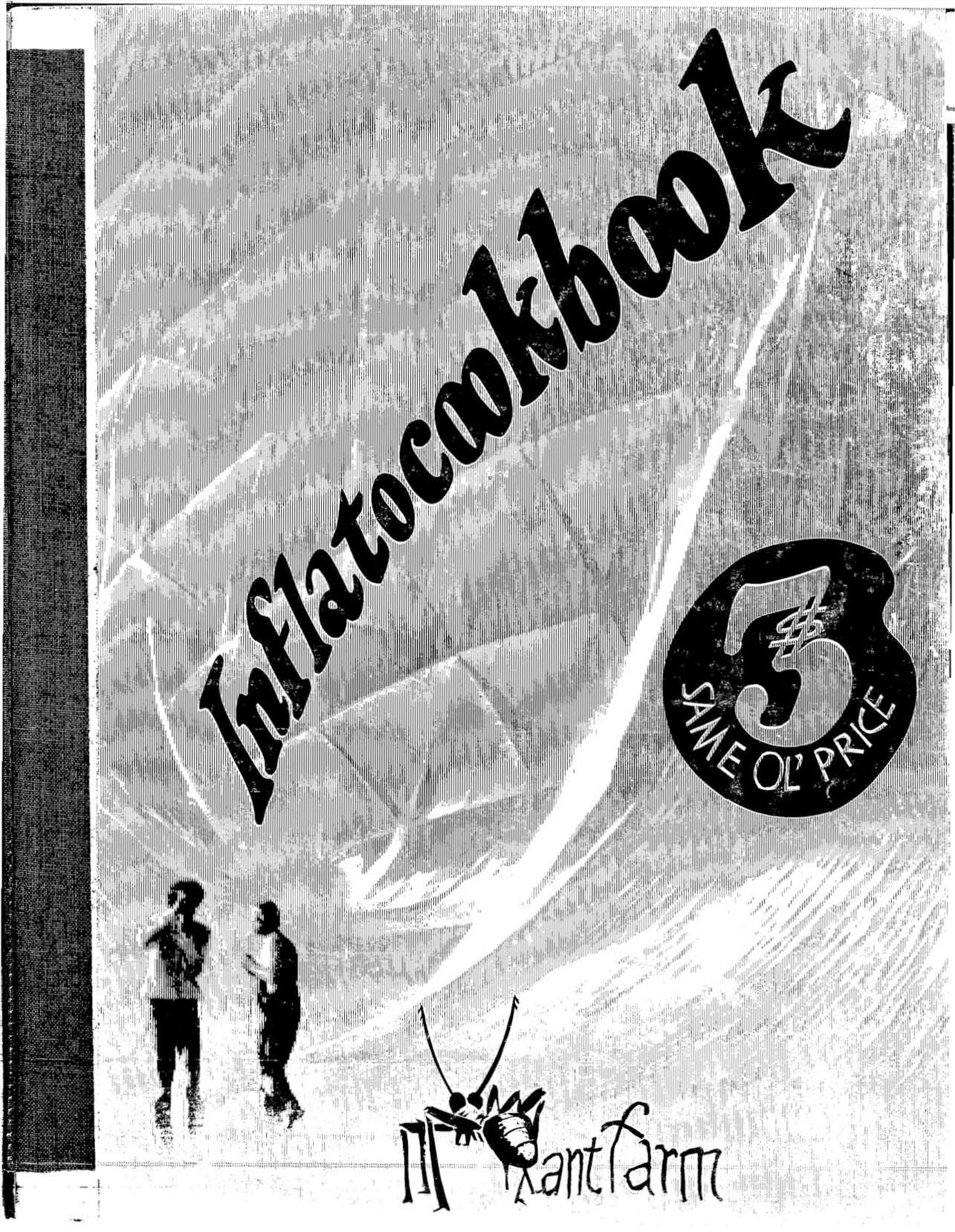

The news report itself was published as a fake forecast for April 22, 1972, a fictional account of the actual performance which occurred on April 22, 1970. The parafictional newsclip can be found in Antfarm’s INFLATOCOOKBOOK, a handbook to all things inflatable — including a collection of images documenting Ant Farm’s 18 month period of touring the country as ‘Inflatoexperts’, part of “a travelling show of inflatable structures and environmental circus”. While the notion of global warming had not yet solidified at that time, the work was deeply rooted in environmental activism. The Berkeley performance, a straightforward while morbid spectacle, pointed a metaphorical gun to each student’s head: the atmosphere will kill you, are you in or are you out? Somehow this environmental drama revealed a far more terrifying truth about its context—the American education campus has always been a site for climate catastrophe and violent sequestering. In 1970 Antfarm’s gang of rock-n-roll characters swarmed around in fake white lab coats and goggles, performing their radicality to wide-eyed students—your little world isn’t safe! they cried. On March 2nd 2021, Education Week’s School Shooting tracker reports 10 incidents into the year so far. It is reported that the number indicates an incredible drop in school shootings. The trend line has been interrupted by a global pandemic. There is another gun to our heads at the moment and all around me I see figures in goggles and masks and riot gear, the world has turned on us—are you in or are you out. Protect ya self.

IN 1997 Romeo Gigli’s tenure at the helm of C.P. Company’s fashion design team ends and Moreno Ferrari becomes Creative Director. The Italian apparel brand, founded in 1971, had established itself as a radical creator of military-inspired outerwear, pushing the boundary of material innovations, processing techniques, and design. In 1988 the world was rocked by the Goggle Jacket, a hooded windproof jacket that could be zipped up to conceal the head and face completely, except for two built-in goggle lenses. Ferrari’s direction pushed the brand’s boundaries through the ’90s, famously introducing the Urban Protection line, and then at the turn of the century, Transformables. Released in 1998, Urban Protection launched conceptual fashion for the modern urban man. The LED Jacket featured a microcomputer in the right breast pocket aimed to indicate air contamination and warn the wearer of exposure to methane, propane, and freon. Over the top, “an almost bulletproof” tactical vest. In 1999 the last piece of the UP line was released, the Solo Jacket. Constructed from Dynafil TS-70 bonded to a Nylon base the jacket featured straps and pockets across the chest and back and came equipped with a tactical gigamega Maglite flashlight. A store in the West End of London sold the Goggle Jackets for £600 calling the jacket “burqas for the boys.” The Transformables line introduced dual-purpose garments that could transform almost instantly into an armchair, a kite, a mattress. Perhaps the boys could play house on the beach or protect themselves from homelessness. C.P. Company set out to protect the boys, from all threats foreign and domestic, as they set out to move through the world—surviving it all.

IN 1894 the ultimate invincible survivalist bouncy big-boy is born. At the Universal and Colonial Exposition in Lyon, French industrialist Édouard Michelin turns to André Michelin pointing at a stack of tires and suggests that sees the figure of a man without arms. Naturally his probably drug-induced hallucination brings forth, four years later, the first drawing of “Bibelobis,” or “Bibendum,” better known as the Michelin Man. In 1898 the official poster was produced— a bulbous inflatable figure with human hands but no eyes and a gaping tire mouth triumphantly toasts a glass to the motto: “Le pneu Michelin boit l’obstacle! The Michelin tyre man drinks up obstacles!” His glass is filled with nails and broken glass.The Michelin Man became one of the most popular corporate humanoid figures of all time, like any good force of conquest, drinking up the world and all its obstacles in the process. Of note is the 1912 transition of the brand’s tires which changed from the original beige color to black because of the use of carbon as a preservative and strengthener of basic rubber. Very briefly did Bibelobis make his appearance as a black tire man before an entire campaign was launched to change back his appearance, citing his darker color to printing and aesthetic issues.

THE SAME YEAR of Moreno Ferrari’s C.P. Company takeover, and 27 years after Ant Farm’s CAP 1500, a bigger badder louder bubble is growing at a local gas station. Melissa Arnette Elliott launches her career with the debut album Supa Dupa Fly and the debut single The Rain, for which a music video is filmed by legendary director Hype Williams and stylist June Ambrose. Missy “Misdemeanor” Elliott is launched to the world as the black Michelin woman. At a time amidst heavy over-sexualization of females in hip hop the idea was insane. Missy establishes that this video is going to change the game. Clad in a patent leather bubble and $25,000 Alain Mikli goggles, the video’s opening shot is paused on the first day of production. Missy is quickly deflating. A team of stylists walked her a whole city block to a gas station where she was inflated with a tire pump. When she returned to the studio at full expansion she was no longer able to dance her choreography. It was at this point that June Ambrose made the decision to keep Missy Elliott in a constant state of de- and re-inflation for the next 16 hours by piercing a hole in the back of the suit. She stood behind her through the shots inflating and leaking the suit. Between takes small fans were dropped inside the suit to cool and expand the bubble. The suit not only works but requires collaborative labor, it is in a constant state of flux, dropping to states of almost-deflation to allow for movement and then springing back to full force, a dance of flaccidity and build-up. Missy Elliott’s largeness, her utter bravado and power, her bling, her teeth, her nose, her lips move forward towards the fish-eye lens taking up the whole screen, she is majestic, strange and beyond human.1 This inflatable is transformable, it is vulnerable and adaptable. It is fly as hell in a way that rejects the male gaze, and the frame of the camera itself. This is protection of another kind.

- Steven Shaviro goes so far as to say ‘cybernetic’ in his 2005 Supa Dupa Fly: Black Women as Cyborgs in Hiphop Videos. Shaviro asks of Missy’s insectoid helmet and sunglasses, “Is this her embodiment of a fly?” to which I say nah, but he’s doing a good job himself in giving Cronenberg’s Seth Bundle a run for his money with that 80’s academic-gone wild look. I kid, Shaviro, but don’t come for Missy. ↩︎