On James Rosenquist, An Interview

Contributors

Fashion

James Rosenquist (1933–2017) produced a diverse catalogue of artifacts and artworks that often read as a visual, historical record of the public imaginary and technological zeitgeist common to the work of the pop artists. His use of advertising as source material and depictions of recognizable brand logos throughout his career demonstrated a critical fascination with consumer products and the ordinary, everyday construction of the self as an image. Indeed, many have cited this as a consequence of his early years spent as a billboard painter in New York. Source material, and material generally, is a site of ingenuity in Rosenquist’s work. Canvases backed with building materials, painted mylar curtains, and pattern-making paper from the Kleenex company can all be found in his oeuvre. In March 2021, we spoke with James’ widow, Mimi Thompson, and his daughter, Lily Rosenquist, as well as Sarah Bancroft, Executive Director of the James Rosenquist Foundation. Front of mind for us all was Rosenquist’s paper suit, which was first produced and worn by the artist in 1966, and later reimagined in a collaboration with Hugo Boss on the occasion of his 1998 exhibition The Swimmer in the Econo-mist at the Deutsche Guggenheim Museum in Berlin. A week after we spoke, French fashion house Lanvin released their 2021 FW collection, in which creative director Bruno Sialelli had printed fragments from Rosenquist paintings onto many of the garments. Now Rosenquist, famous for his technique of collaging together images from myriad sources, is himself sampled: his slick tubes of lipstick and explosive depictions of the cosmos cut up, re-scaled, and re-presented in the studio of another creator.

—March 4th— 2021

Igor Bragado

Miles Gertler

Mimi Thompson

Lily Rosenquist

Sarah Bancroft

IGOR BRAGADO—It was also, well for sure you know this, but Miles and I, through our research and our work on death and daily life and the military and the gesture and the hand, we kept coming back to James’ work in one form or another, but always super informally.

MILES GERTLER—I’m joining this call from Toronto, and we know that one of the times that Jim (James) wore the Paper Suit was when he appeared on a panel at the AGO in Toronto alongside Marshall MacLuhan and we were just curious, how did the suit travel? Did it fold, or did the owner have to wear it on his own body on the plane?

MIMI THOMPSON—I can only speak about the second round of suits made in 1998, but you could fold it up, absolutely. Jim usually carried it in a little suit bag because he loved it so much. The second suit was made of Tyvek. The big problem that Jim always had was that the seam in the rear end was always splitting—well, not always but often. And that happened with the original suit made in the 1960s too. I think he was in Tokyo, at a geisha parlour, and he sat down and heard a rip—and that was a different kind of paper. But the Tyvek was pretty indestructible aside from the seams really, and you could spill on it and you could wipe it off… it was kind of great.

SARAH BANCROFT—The first suit Jim had made for him in 1966 using paper from the Kleenex company, and it was brown paper, and I actually think it was like pattern-making paper, stiff, so after wearing it several times he could definitely fold it, it became pliable. And the second suit that Mimi is talking about was made in 1998 by Hugo Boss, on the occasion of the Rosenquist The Swimmer in the Econo-mist exhibition at the Deutsche Guggenheim Berlin, and it was a wonderful re-imagining of the suit, but as Mimi said it was Tyvek, which is the same material that a FedEx envelope is made of and is kind of indestructible. I think it’s used in construction, too, as siding to waterproof houses…

IB—Miles, sorry, just one second—are we recording this?

MG—I am, yes.

IB—We are! Nice. Good.

MG—How many of the Hugo Boss suits were produced, and were they all dimensioned to Jim’s body? To the original?

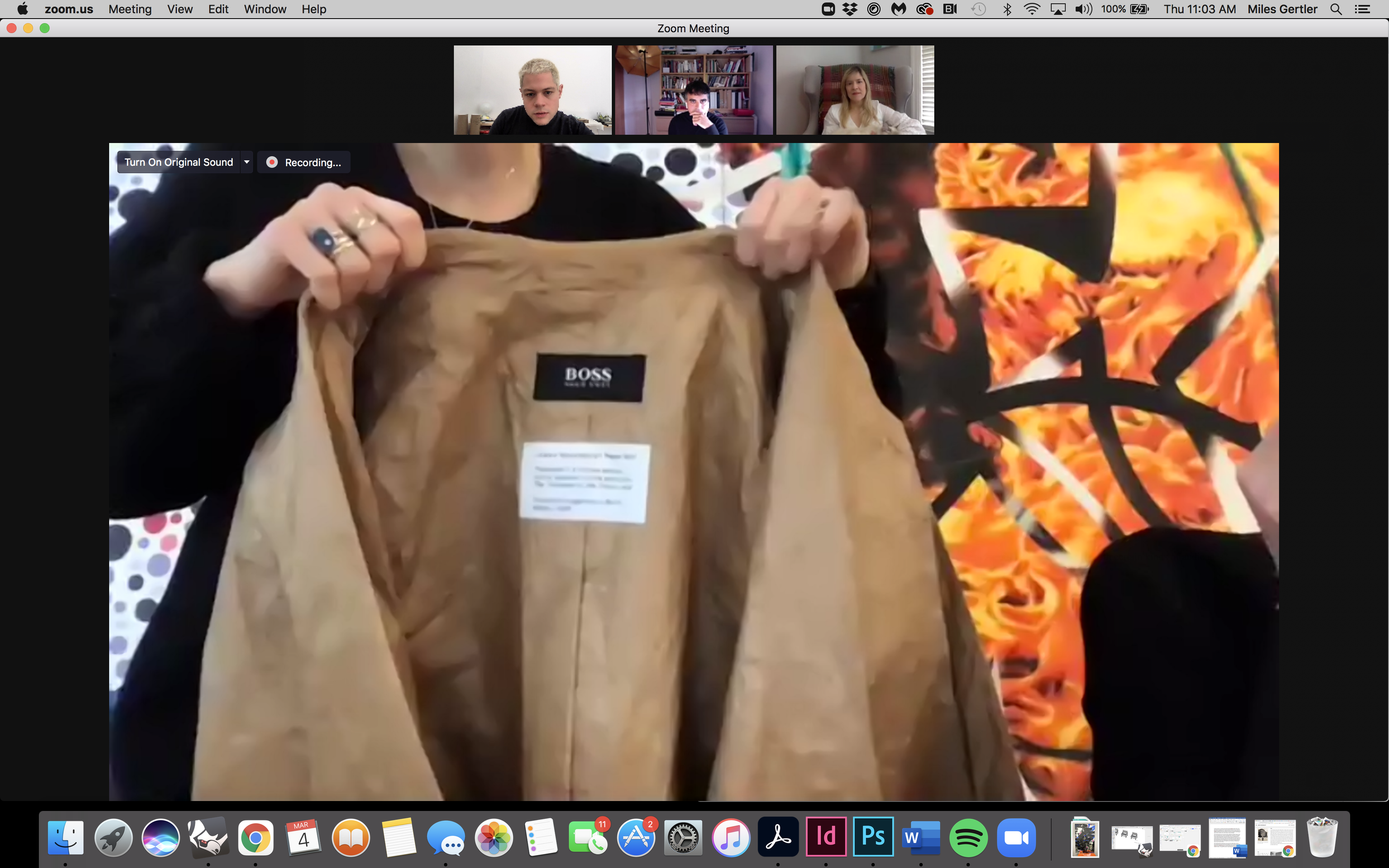

SB—I know some of these answers. It was a limited edition of 250 suits. I believe they were done in two colors: brown and black. And I believe they were in a range of sizes, because although it was a special limited edition, they did sell them—they were 45 dollars each—so they did have a range of sizes. I don’t think it was a direct copy of the original suit. You know, it was Hugo Boss, it was a re-interpretation.

MT—Yes, it was. Stylistically it was a little different. The second suit came in a box which had scissors, so if the pants were too long or if the arms were too long you could cut them to size.

MG—We’ve seen that!

IB—The Kretzer Sheren scissors. Since there’s a material change with the second suit made of Tyvek, which is more durable, we were wondering if bringing the scissors to the edition was to make it a bit more unstable, like the first suit—not appearing to be as durable. But also, it’s a bit strange right, because you’re purchasing an art piece and I don’t think anyone would cut it, I guess. Do you know of anyone who actually did?

MT—I think Jim did cut the legs on his own once.

LILY ROSENQUIST—That’s also his suit, so he would feel free to alter it as he liked.

MT—That’s true.

LR—I was doing some research on this before we gathered to talk, looking for event photos of someone wearing the suit at that time, and the only photo I could find of someone wearing it was from some society magazine from Alberta, Canada, and the article was, 90s Supermodels: Where Are They Now? And there was a photo of a male model, probably at the Hugo Boss event, wearing the paper suit… So he wore it!

MT—I feel that most people that bought that suit saw it as an art object and kept it in its box. A lot of them come up on eBay and most of them haven’t been worn.

LR: And that photo might have been from an event that Hugo Boss did where they hired models to wear the suit.

MG: In Painting Below Zero, I think Jim says he wore his original suit about 8 times before it fell apart in Japan, and he said about the content in his paintings that he was often working with source material that was too recent to elicit nostalgia but not recent enough to appeal to zeitgeist appetites. It was sort of ahistorical and the paper suit is sort of similarly abject. Like, it’s never as crisp as when it’s first worn, but it’s not durable enough to really gain the aura of a historical artifact, a least while it’s being worn by him. So it has no sense of history other than the wrinkles visible in its surface. But I’m curious about the fact that when it fell apart, it was done. Because, there are paintings that Jim re-painted or re-worked or re-presented, like the Candidate as Silo, but do you have a sense of why the paper suit wasn’t reproduced immediately in 1967, when he was known as the Man in the Paper Suit—why not re-make it then?

MT: That’s a good question, but I think he liked the ephemeral quality of it all. And he was happy that when it was no longer wearable, he could just toss it. There’s a quote from him where he says he felt like a paper bag himself, and like everything could be over for him by next week; he was interested in that idea of “here today, gone tomorrow.” I don’t think he had a feeling that he wanted to continue the suit, although he did love it when Hugo Boss brought it back to life. It’s like with his paintings, you know, although he does repeat certain images throughout his work— once he examines an idea as much as he can he moves on to the next one.

SB: I agree, I think the idea of ephemerality was very comfortable to him in every way. He kind of did the same thing in his everyday life. Rather than going to a material to make a traditional suit he was thinking about it sideways: he went to a material of creativity, of construction that artists use—whether they be designers or dressmakers—knowing it wouldn’t last and being quite comfortable with making a disposable suit. And you see this idea of ephemerality in his artwork as well and I see it so powerfully in a work that Lily owns called Reification. I had a conversation with him about the work. It has lightbulbs that turn on and evoke the lights of Broadway and Time Square, and it spells out the first three letters of Reification, to bring abstract ideas into concrete form, and as the lightbulbs burned out, he did not replace them. Because we were showing it at the Guggenheim, it could only be turned on for the opening night as it was so delicate and something of a fire hazard. The construction is phenomenal, but it’s totally outdated. I asked him, “What do we do if a bulb burns out?” And he said, “It’s had a life of its own. That’s its life. I’m okay with that.” As the bulbs burnt out, he was fine just leaving it. Not every artist approaches their work like that. You see this through-line of ephemerality early on, with the paper suit. I don’t think he thought of conserving it—that was never his bag, so to speak.

MT:Yes, he just threw them in the trash when he was done.

MG: And so what did remain of the original 60s suit in 1998?

MT: That’s a good question. The Hugo Boss suit is in the Met, in the Costume Institute, I’m not sure how many of the earlier paper suits were made…

SB: There may have been two…

IB: Wait, wasn’t there only one or…

MT: I think there was more than one.

SB: I think there may have been more.

MT: Well, I just told Miles and Sarah this, Igor, but I recently was in touch with Horst, who made the suit. He’s a friend of my friend Judy, and I’m going to see him next week, to find out more details. Apparently Horst originally wanted to make a different kind of suit. Jim wanted him to make it out of Kleenex craft paper, but Horst wanted to make it silver and sequins… he said, “I wanted to make it really shiny, so it would twinkle,” and Jim said, “No! I just want the paper.”

IB: And who is Horst?

MT: Jim called Horst a couturier: he used to make a lot of leather clothes in the East Village… He made all kinds of things.

LR: He was very much a man about town and went to a lot of the same parties that Jim did in the 60s and it sounds like they travelled in the same group.

IB: It would be interesting to ask him if the paper suit was actually cheaper to produce than any other suit, because Jim speaks about this in interviews, saying that because he didn’t have money at the time, he chose paper…

SB: Same question. This morning I woke up thinking that the process of making the suit wouldn’t have been any less expensive. And maybe it’s harder to sew paper than fabric!

MT: They were really good friends. Jim spoke so fondly of him always.

MG: When there was mending to be done, or when a seam split, was it Horst who would repair or remake the garment, or did Jim ever attempt to do that for himself? I could imagine there would have been some creative solutions…

MT: Yes, I think there probably were. I can only speak to the more recent suit, and I remember him taping it on the inside once, thinking, “I don’t think that’s really going to do it,” but it was often a tape thing, rather than a sewing thing… Although Jim did know how to sew. And iron.

IB: He said that he felt he was a paper bag when he was wearing it. This quote in Painting Below Zero is incredible, where he said that the paper suit was disposable, and fed into the idea of the disposable person… I think this also relates to that idea, Mimi, that he was maybe here today, but could be gone tomorrow, and maybe he wasn’t interested in building something durable. But I’m wondering if using paper for a suit in the 60s had the same connotation it has today. We’ve seen some of the paper dresses that were released in the 1960s, like the Campbell’s Soup dress, and they feel very fine and highly produced—not disposable at all. But this suit itself was meant to look cheap.

MT: I don’t know if he wanted it to look cheap. He really liked the paper dresses; they were really fashionable at the time and you saw people wearing them on the street. His suit was also a commentary on The Man in the Grey Flannel Suit which of course was a riff on the group think and conservative outfits of the salary man. And of course, a paper suit isn’t conservative at all. I think he just thought it was an interesting idea.

SB: I agree, I think his sensibility was more about stopping the viewer in their tracks, the way he wanted his work to slow people down. Initially it would have been a very crisp, well-tailored suit, but in a totally unexpected material, and that is consistent in his work. I think he wanted it to look very sharp but had no problem with it looking cheap over time as it degraded.

MG: Sarah you’ve spoken previously about the surrealist lens through which Jim’s work can be seen. This strikes us as a surrealist piece. In a 2003 article in Art Forum, Michael Lobel writes that in Jim’s paintings, he offers “a recognizable image that nonetheless melts at various points into abstraction.” Do you see the suit as a surrealist contribution to his body of work?

SB: I’ve never thought of it that way, but I absolutely can see that and certainly Jim was constantly saying that he related to surrealism and would see himself more as a surrealist than a pop artist. Of course, all the pop artists knew that pop art was really the melée in which they’d been placed in but it wasn’t a label they gave themselves and the label Jim related to was surrealism. I don’t know how much he used that term in the 60s, but definitely… and it’s that idea of the dissociation with reality through the use of paper.

MG: I could imagine the man in the paper suit striding, crumpling, through the uncanny valley.

SB: It probably wore him!

MT: It made a lot of noise sometimes.

LR: It still does. We have the Hugo Boss suit and whenever you move it around it rustles.

MG: And this is probably an accident of photography but when you look at the catalogue photo of the 1998 suit in the Met collection on the mannequin, it really does look like one of Magritte’s headless suited bodies.

IB: We came across this beautiful photo in the Painting as Immersion catalogue, in which Jim is wearing one of his preparatory collages taped across his chest. It seems to be backwards though. Is that a mirror in his hand? What’s going on here?

LR: I believe he’s working on a lithography plate, and when you work on a litho you have to work backwards.

SB: It’s not so much him wearing it, but it’s a great example of Jim’s practicality. In order to create the print he needs to be able to see the collage and see it in reverse, so he holds a mirror to it so he can transfer that to the plate. He does this a lot over the years in different ways. He’s not dressed so much as looking.

LR: Something he did wear though: he made a mask for the Outsiders Ball, which is such an interesting work too. It looks so flat when its photographed but is actually this very dimensional thing.

MG: Was that made of paper?

MT: Paper and fake flowers.

MG: Igor and I have a fondness for fake flowers.

IB: Was it a one-off?

MT: Yes, it was for an AIDS charity auction. A friend in Staten Island would hold it every year and Jim made a few of these for benefits over the years.

MG: In his chronology as an artist, it seems that things happen very quickly for him once he decides to become a fine art painter. One thing that seems extraordinary is that the Kleenex company was willing to give this artist paper. Brands, and a comfort with them, are present throughout Jim’s career. Do you know more about the connection to the Kleenex company?

SB: I was thinking about this in terms of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology) which fostered collaboration between artists and industry. Billy Klüver was super involved with it. He was an engineer at Bell Labs. A company like Kleenex might have had a familiarity with artists at that time. Though they may not have been involved in E.A.T. specifically, industrial collaborations with sculptors or painters weren’t uncommon.

LR: Part of it does speak to the time. It does seem like an opportunity unique to the 60s.

MG: And do you know what Jim’s financial situation was in 1966 when he had this made?

MT: He sold many paintings at that time, but not for a lot of money, really. He always lived pretty much hand-to-mouth, even when he was very well-known in the art world. He had a wife and a son who was born in ’64 and he also helped his parents, so he never had a lot of extra cash on hand. He worked hard all the time because he had a lot of responsibilities.

SB: You’re right that things happened so quickly for him. In 1960 he quits painting on the boards and by 1962 he has his first show. By ’63 pop art and his career have taken off abruptly and he’s selling work but the price is maybe only 500 dollars for a painting. He had more financial stability than he did before, but he’s not rich by any means. Something shifts in ’65 and ’66 might have been a unique year in the decade for him, financially, because in ’65 he sold F-111, which was his biggest work at that time and it sold to the Sculls, and there are a number of articles at the time which reported on the price (and the price varies according to the article) some people say 50,000, others say 60 or 65,000, and let’s say he got half of that, if it were a 50/50 split with the gallery… that would have been a big chunk of change, a lot more than any other show.

MT: Absolutely, but it all had to go in so many different directions for him.

SB: And maybe that’s what he made that year, for the whole year.

MT: We have this wonderful notebook of Jim’s from the 60s that we made facsimiles of. And in it he drew a miniature of every painting he made each year and wrote how much he sold it for and to whom.

MG: On the rear of the painting Vanity Unfair for Gordon Matta Clark, Jim used a recognizable wood board veneer as a backing for the canvas. Did he do that a lot?

MT: Yes. Materials just caught his eye. Things that were not traditional art materials. He always liked to go to flea markets and find stuff; he was attracted to the leftovers of human activity.

LR: And it’s just his resourcefulness as well. I believe that the wooden panels on the backs of paintings were used because it was hard to find a piece of wood that large and that flat but that siding was widely available.

IB: Once he had the suits from Boss… when would he wear it? When would he make the choice to put one on?

MT: He was always very conscious of what he wore. With the paper suits, I always felt that he had the need to be observed, not as an artwork per se, but as a presentation of who he was and what he did. He wore them a lot for certain periods, and then he wouldn’t wear them, and then suddenly he’d have them on again. The only other suit he had that same connection to was a suit that he got in London when he had a show at the Haunch of Venison. It was black and silver swirls—it’s the craziest suit. He saw it in a store in London and the gallerist bought it for him because he was so excited about it. He wore it to the opening. And when he wanted to make a statement it was either the paper suit or the swirly suit.

LR: It was for occasions. Otherwise he had a closet of black t-shirts and blue jeans and he would go to Walmart and buy 50 pairs of the same pair of pants and the same black t-shirt and the same reading glasses.

MG: I remember that one of his favorite colors to wear was a bright cerulean. He had at least one of these blue shirts and it was so close to the colour of paint he used to elaborate the ornamental details on the façade of his studio building on Chambers Street. This seemed like a deliberate choice, to put that on the building, on the street.

MT: He loved that color and those shirts. First he bought a really fancy one and he wore that all the time. And then he decided they were too expensive to buy, so he found a white version at K-Mart and dyed it. Then K-Mart began making shirts in that same blue so he stopped dying the white shirts and bought as many as he could.

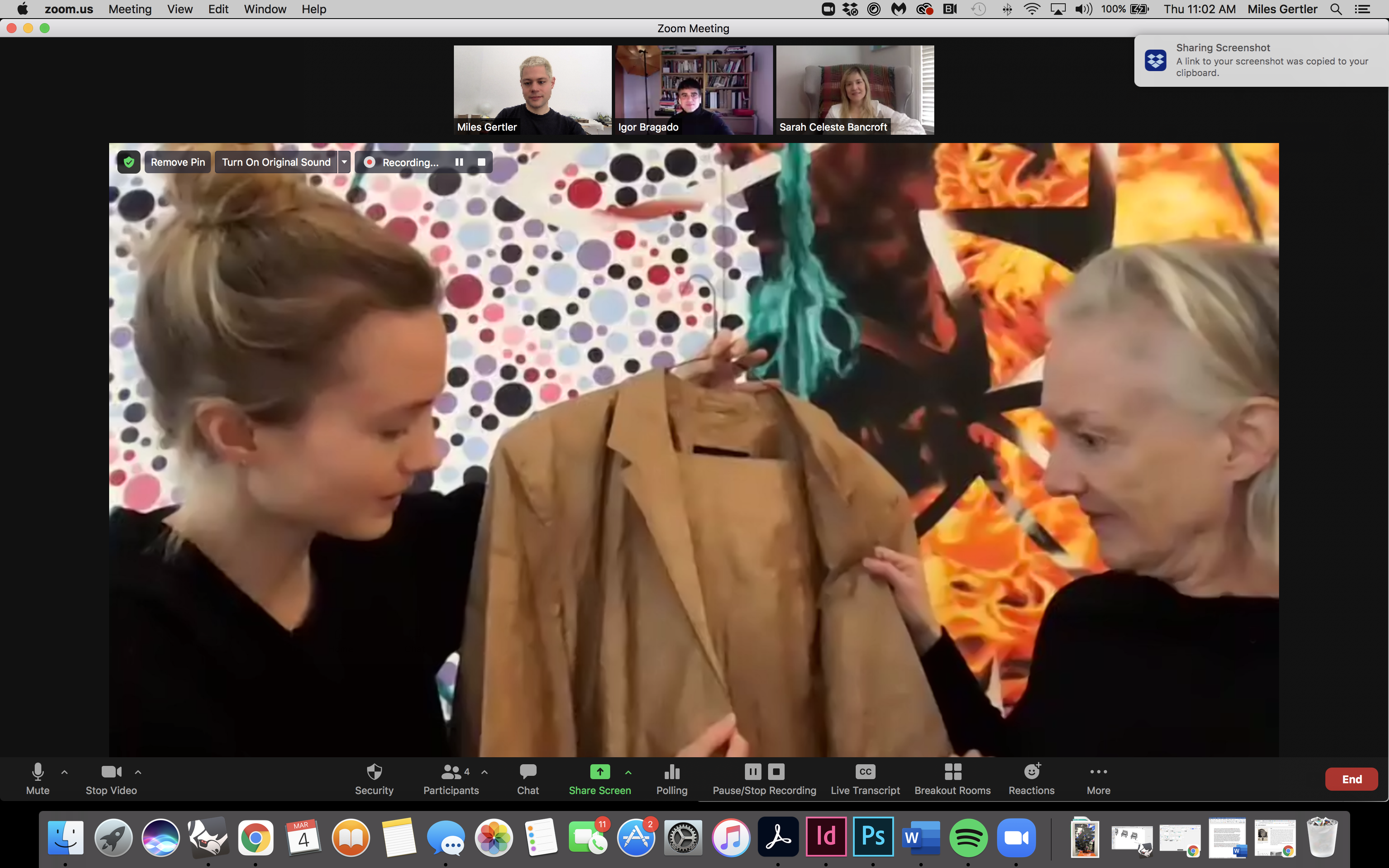

LR: By the way, we have the paper suit here if you want to look at it. I know it’s weird to look at something through Zoom, but…

IB: That would be lovely, yes!

——

A few weeks following our interview, Mimi Thompson had a chance to meet with the fashion designer Horst and confirm a few facts around the original suit’s production. Mimi reports the following:

“Horst only made one suit for Jim, and used needle, thread and sometimes a little glue. The paper had thread running through it to prevent it from tearing. The reason Jim wanted to make the paper suit: he knew that Horst was creating a paper suit for the actor Steve McQueen. A photo of this project, showing McQueen in a paper suit (made of paper-like non-woven acetate) surrounded by women in paper dresses, appeared in Look Magazine in 1967, although Jim’s suit was made in 1966. Horst and Jim met downtown, either at the Cedar Bar or Max’s Kansas City, and, when they wanted to meet at the latter, they said, ‘I’ll meet you in Kansas.’”

Reification, 1961. Oil on canvas and chromed steel, with electric lights and sockets. 24” x 30” (61.0 x 76.2 cm). Collection of the Estate of James Rosenquist. Courtesy of James Rosenquist Foundation © 2021 James Rosenquist Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Rosenquist wearing the mask he designed for the Outsiders Masked Ball benefit auction, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, California, 1992. Courtesy of James Rosenquist Studio © 2021 James Rosenquist, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

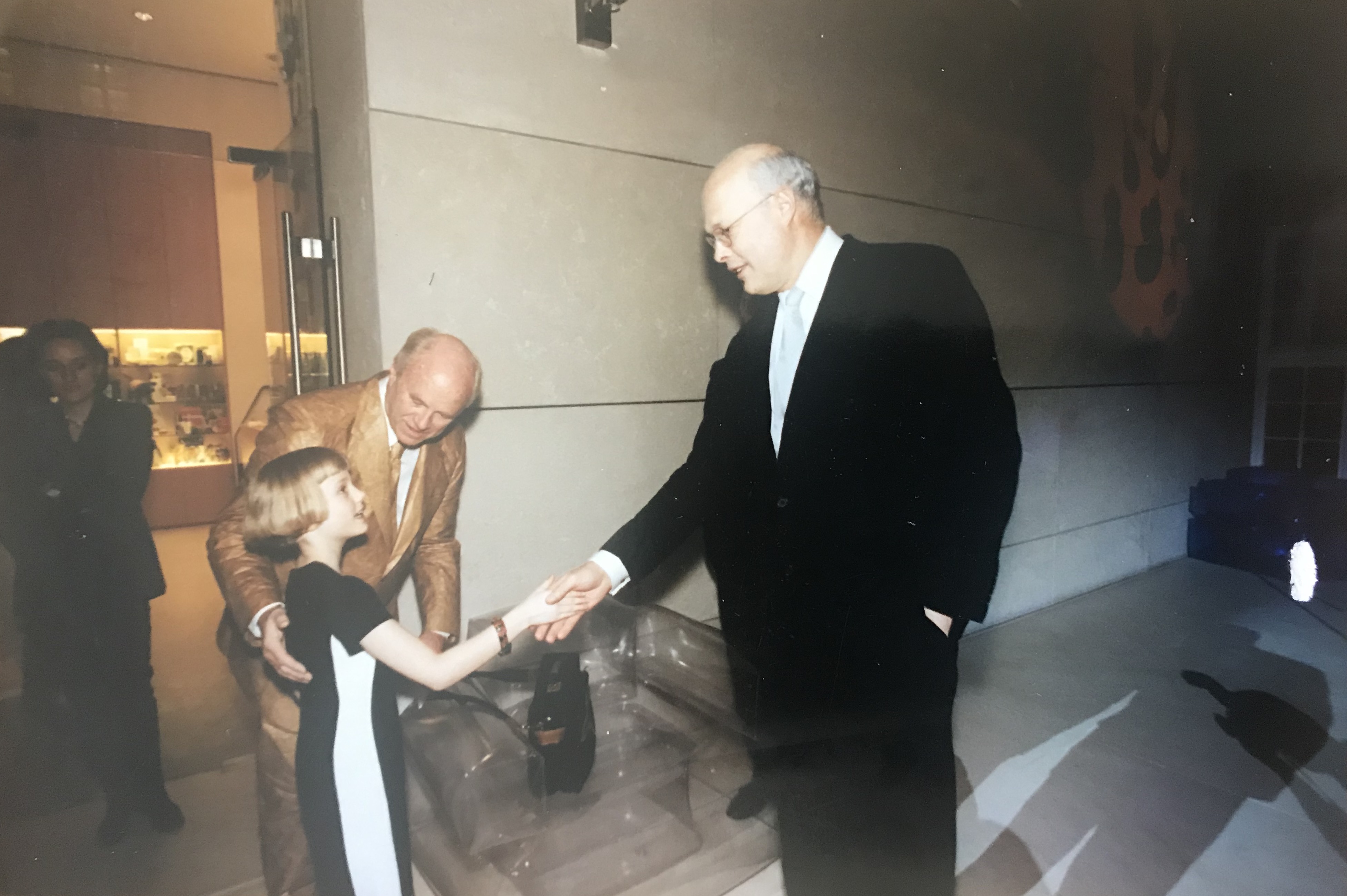

James Rosenquist introducing Lily Rosenquist to Tom Krens at the opening of The Swimmer in the Econo-mist at the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, 1998. Courtesy the James Rosenquist Estate © 2021. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

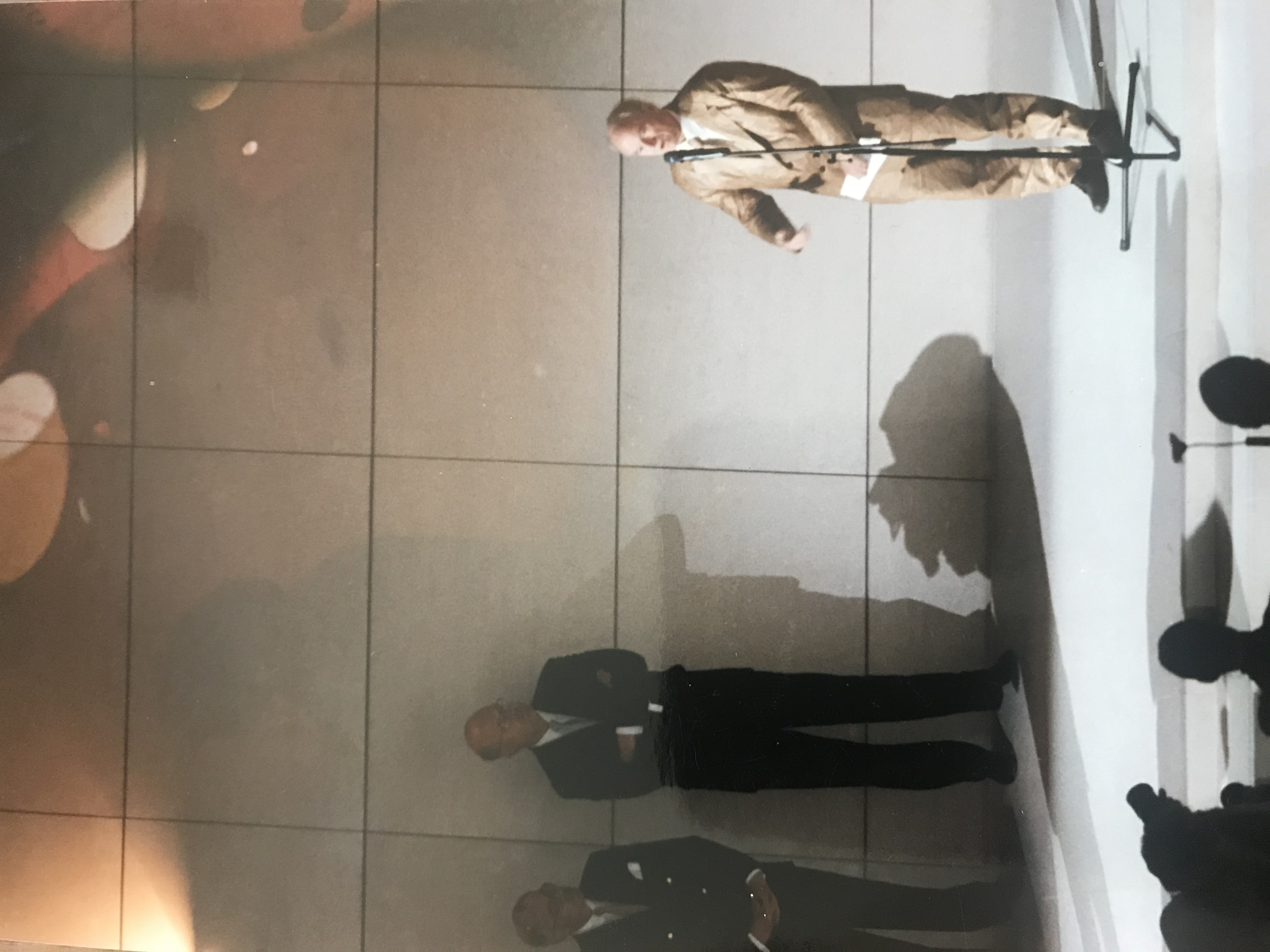

James Rosenquist speaking at the opening of The Swimmer in the Econo-mist at the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, 1998. Courtesy the James Rosenquist Estate © 2021. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

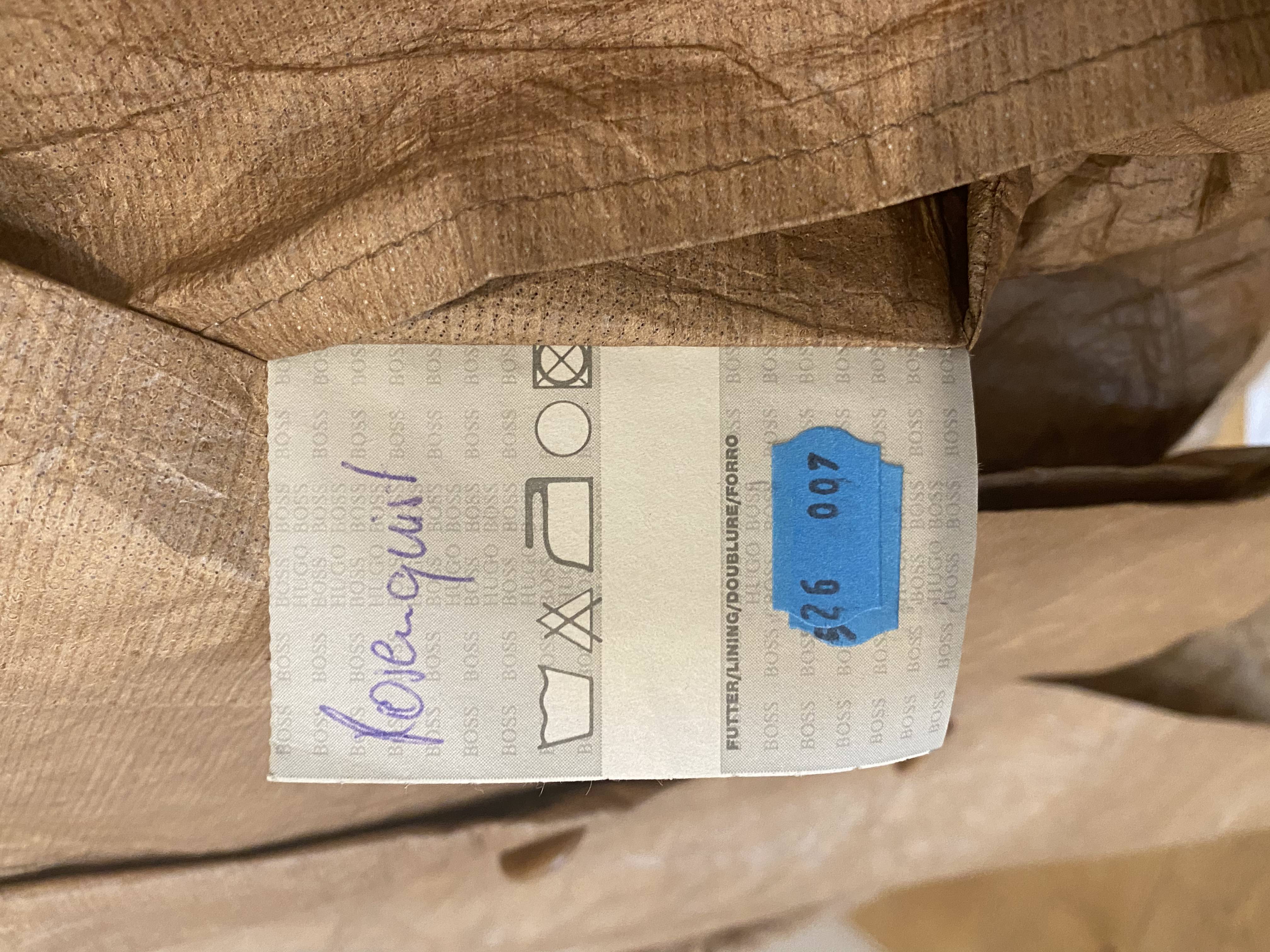

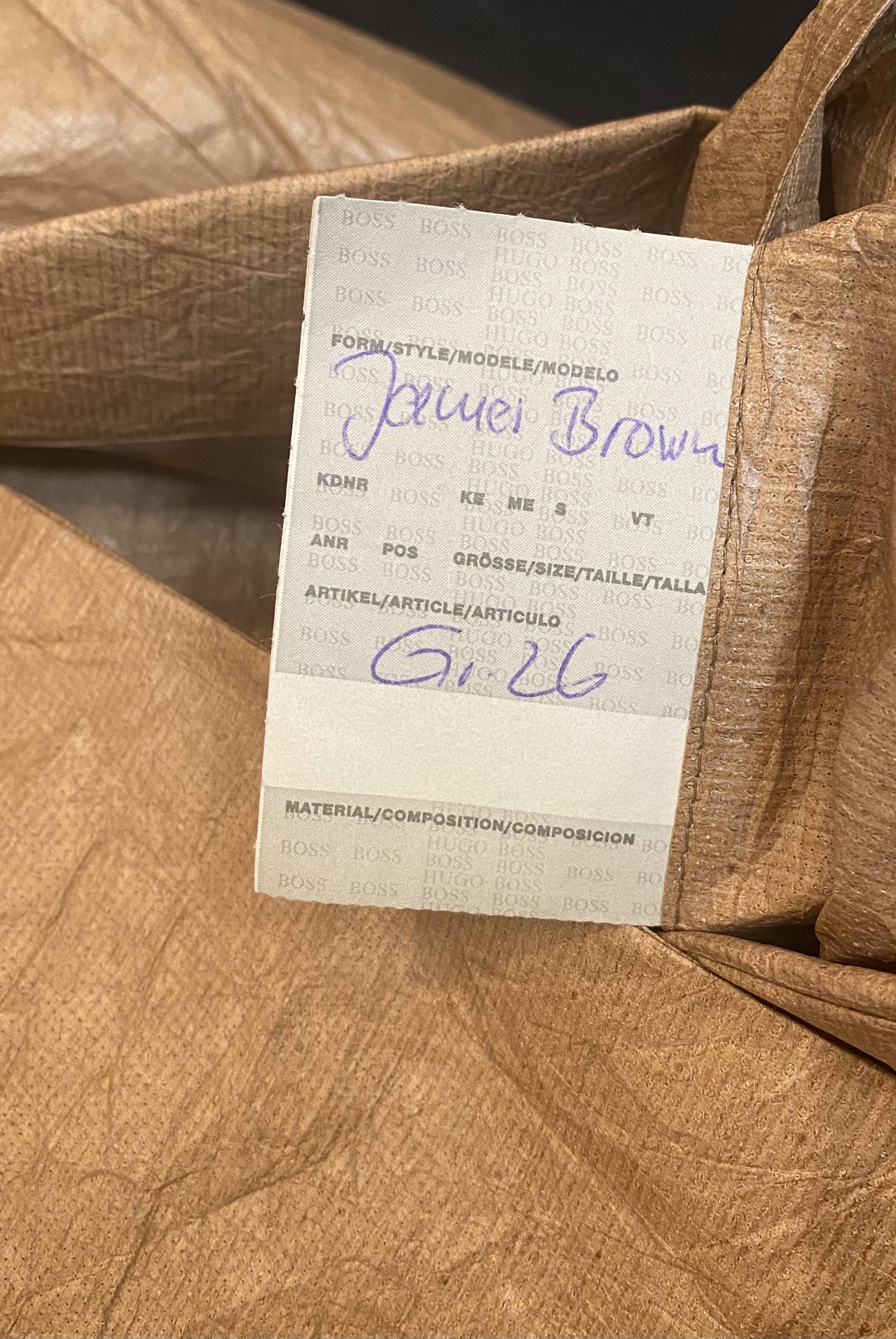

Interior tag of the 1998 Hugo Boss paper suit. Courtesy of James Rosenquist Studio © 2021 James Rosenquist, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Interior tag of the 1998 Hugo Boss paper suit. Courtesy of James Rosenquist Studio © 2021 James Rosenquist, Inc. / Licensed by Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Used by permission. All rights reserved.

Lily Rosenquist and Mimi Thompson exhibit James Rosenquist’s own 1998 Hugo Boss Paper Suit during the interview with Igor Bragado, Miles Gertler, and Sarah Bancroft.

Lily Rosenquist and Mimi Thompson exhibit James Rosenquist’s own 1998 Hugo Boss Paper Suit during the interview with Igor Bragado, Miles Gertler, and Sarah Bancroft.