Interview with Mira Henry and Matthew Au

Contributors

Fashion

TOMI LAJA

Do you see your design and aesthetic practice within Current Interests as a form of fashioning boundaries? You have physically quilted, sewn, and tailored materials for projects, and several works also deal with the posture of the forms you work with. Is there an understanding of the architectural work as a body?

MATTHEW AU

Mira and I tend not to explicitly speak of the work as a body, the term can get problematic, but we do discuss posture that might speak to a bodily gesture. We more often think of these in terms of the way posture is read in cladding—how forms hang and support, sag, lean, or clump. For instance, the notion of the ‘oversized’, like the way an exaggeratedly puffy jacket with its excess of insulation builds up and stacks against one’s shoulders tends to hide a lot of features as it relaxes, leans, and tilts. We are interested in these details as places where the building projects itself back out into the world and produces certain qualities, attitudes, and ways of being. Perhaps it is less boundary making and more fashioning contextual signals between the building and its context.

MIRA HENRY

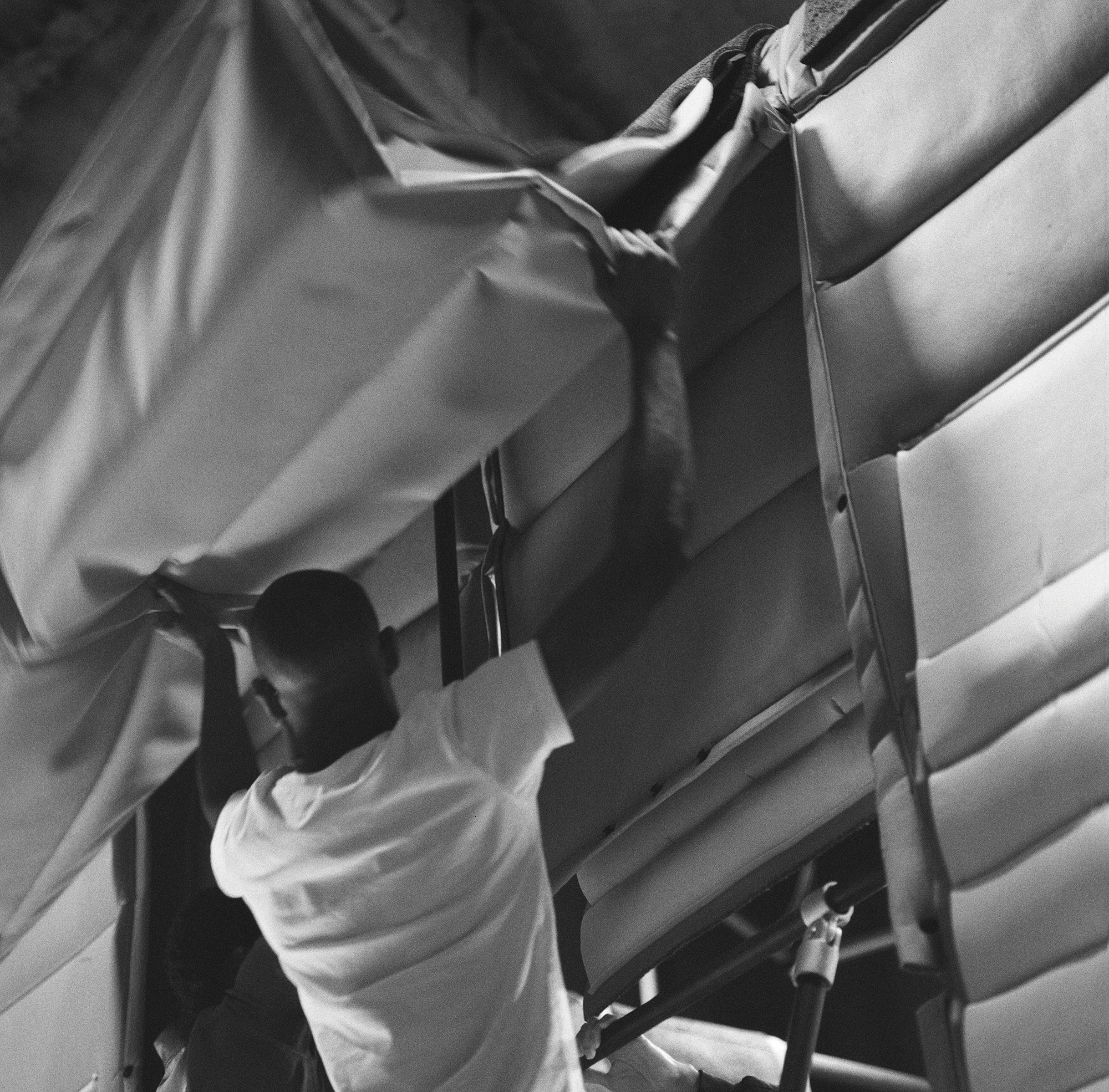

There are other ways to think about fashion in our work in terms of the process, the imaginary, and the tectonics behind it. When taken as a verb, to fashion, the term really speaks to a physical act that unfolds in time. We like how fashioning orients us towards the performance of an assembly. This is very relevant since we gather, bundle, or hang forms onto each other. There is increased agency and directness in this way of working in the same way that there is agency in self-fashioning and personal style.

TL

Can you expand on your statement regarding the body analogy as problematic and discuss how you are speaking about architecture in relation to the body rather than as a body?

MH

I would perhaps reframe the language a bit. The stickiness is embedded in the discourse of the garment and cladding beginning with Gottfried Semper. I have always been so drawn to Semper’s work because of his focus on craft tectonics in the global south. And yet his anthropological approach comes directly out of colonial constructs. The exploitation and cultural extraction that this history comes out of has always never seemed to be acknowledged, which is painful. I shared my thoughts about this in the piece I wrote in Log 48.1

Semper and then Loos compare building cladding with dress, skin, and mask. This discourse is deeply charged with race (and gender). Anne Anlin Cheng’s book Second Skin: Josephine Baker and the Modern Surface and Charles Davis II’s seminal book Building Character: The Racial Politics of Modern Architectural Style both expose this precisely and directly. Davis argues that the idea of style and character, which for a long time remained neutral formalist terms, are fundamentally constructed through ideas of race. We think about this in our work as we try and inflect new forms of agency within the discourse. When it comes down to it, we find it a really beautiful notion to think about the building as a garment and the ways people who live in them can fashion them as much as the architects can imagine them.

TL

How does your work consider its own fashioning and what is the role of craft, construction, and labor in your work?

MH

That is an important part of who we are as a partnership. We both really love craft and making and yet want to avoid slipping into full arts and crafts revival—fashioning every screw we use. We are always trying to find a balance between the improvisation and inventiveness of making things on our own and the ability and desire to scale. One of the things that we do is align our modes of detailing with standard forms of construction. We are thinking about how to fashion within standard logics. Honestly, we are having this conversation in real time with every project—not just can we do it or how we do it, but how can it scale? It is not the only metric for a successful solution, but it is, nonetheless, always balancing our approach.

TL

In Rough Coat, your 2018 exhibition at the SCI-Arc Gallery, I appreciated, Mira, your critique on objective distance, as well as the embrace of subjectivity and identity in your work. Is there a politics regarding your robust attention to materiality? Do you see materiality as a technique for other infrastructures to grow out of—whether socially, culturally, or experimentally?

MH

I think that questions of politics and materiality are the sweet spot where we, as two individuals, overlap. In our current design studio at the GSD, the contemporary artist Nikita Gale guest lectured on the idea of archeology as a lens to understand how material carries politics and memory. For her, working on and with materiality is a way of implying identities without overexposing the very subjects she is attending to. This loops us back to the conversation around the body and in this case forms of refusal. Material is a cultural artifact. With it comes history, politics, economics, techniques, aesthetics. In our work we like to move into these complex layers and build meaning. It is a method of working that feels rewarding and is something we can work on together for a very, very long time. This is our life’s work.

MA

Even in thinking about our office name, we wanted to convey an idea of our subjectivity, our current and developing interests, which in some ways is at odds with many contemporary office names that convey objectivity. The projects become the sort of background support for conversations around photography, or around politics, or around any number of other relationships that can emerge through attending to the actual material at hand.

MH

I would also add that I think the idea of a material practice in conversations around race is coming. People who I respect a great deal, Darell Fields, Charles Davis II, who have contributed in important ways to conversations about Black phenomenology have eschewed the relationship of materiality and race in the context of a Black architecture project. My sense is this is a holdover from the problematic constructs embedded in Regionalism. We begin to see now in the Black Reconstruction project at MoMA that material is a big deal. It’s emerging, and it’s a part of a rich new conversation that a more diverse set of voices in the field are establishing in a robust and complex manner right now. I want to write about it actually.

TL

I was struck by your beautiful portraits of the facades and lawns of single family homes in Los Angeles. The landscaping, awnings, and shrubbery become a vernacular extension of the facade of the homes, increasing the thickness and depth of their boundaries. Aligning this research with your design practice, many of your projects present as thickened sheds. Can you speak more on your understanding of privacy, intimacy, and interiority through the use of “blankets” in these sheds. I think I first saw and heard about the blanket in Rough Coat, but it is also present in the Silverhouse project as well. In many ways, blankets are aligned with intimacy and safety and I am reminded of how children use blankets to create forts. How do privacy and interiority play into the use of “blankets” as well?

MH

It is a funny thing, but it is true. Looking at those houses led me to the idea of the blanket—or as I put it in Rough Coat—“a façade scaled blanket”. Early on in our collaboration Matthew pointed out that the reason why those images are so powerful is because of all the density and intensity in the narrow field of the facade and the pressure that was put on them. As a design problem that we have continued to work on, this has translated into thinking about the presence of a façade in the city and how a building “looks out” into the world. The research has also lead us to an understanding of surface organized formally through things like layering, folding, thickening, darkening, and casually arranging. As an aside, you know, Matthew and I were both trained as students in the NURBS surface era when everyone was figuring out how to model complex surfaces. The surface conversation for us has really shifted away from geometry, and towards one focused on its social and material potential.

The homes we were photographing are beautiful and their beauty is about maintenance and time and detail created by shrubbery, paint, window grills, and curtains. While we are thinking about these existing conditions in the city, back in the office we are working on constructing certain surfaces through sewing, padding, tinting, dying, and coating. The process of seeing and sensing the built environment began to overlap and radically inform our techniques of working. The blanket has a broad set of associations as something that could be comforting, but also could be something pretty badass. We did a short piece that should be published soon in which we are looking at the diverse manifestations of blankets from a solar blanket or a bulletproof vest that is tailored and protective, to a bedquilt that is casual and intimate as it touches your skin. In all cases it’s a technological surface with immense soft power. We love that this work opens the possibility of an architecture that is provisional, precarious, and live. It has also allowed us to engage in questions of thermal comfort and sound control. We have been talking a lot about dampening, both acoustically and visually.

MA

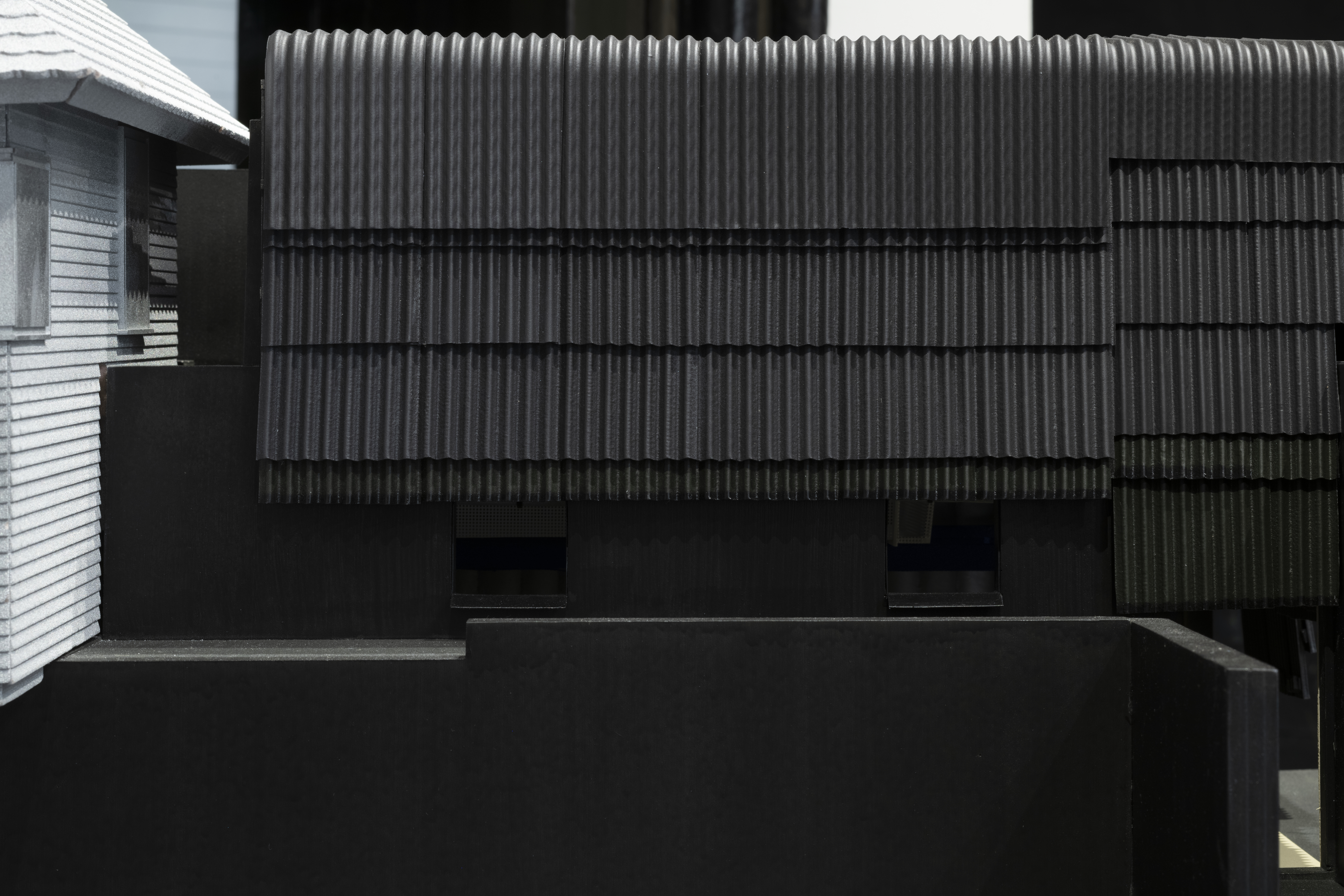

Also, the dampening of images. Early in the design of Silverhouse Studio we realized that the dark, richly hued shingles of our cladding set against the silver-painted house in the background and silver Tyvek interior insulation “blanket” were impossible to photograph, every image we took of our models seemed to be overexposed. The silver against the dark acted like those reflective scarves celebrities wear to blackout the flash from paparazzi. For us, this was an interesting dimension to the project. It revealed both an unexpected optical instability to the façade, the way it refused imaging, but also pointed us to a material history of photography itself, the well documented bias of color film that carried over into digital processing. We ended up building this condition into our exhibition of Silverhouse wall mockups at Princeton, it required us to keep the lights down low. We saw it as one of many layers that work to build up a separation between the interior and the exterior in different ways—either through optical, thermal or other environmental means. That layering for us was important because it was a way for us to shut off the exterior world—to produce a space in the interior that was, in a way, protected from the pressures of the exterior—kind of like what you are describing with the children’s forts. You set up the blanket, because you’re building a private realm that’s separate from all of the external pressures of the world.

MH

—and yet intimately connected to it.

MA

Yeah.

MH

Yeah, that is better than the history or the biography of the blanketed surface. Maybe the biography is not that interesting. What it is maybe better than why.

MA

(Nods)

MH

By the way, did you say you are making a shirt with this issue? Is it going to be neon or is paprika the only color option?

MA: Maybe you could make it out of the old carpet removed from the art and architecture building?

- Henry, Mira, and John Cooper. “Curly Crown: A Moment in Conversation.” Log, no. 48 (2020): 127–34. ↩︎