Judges Cave

Contributor

Fables

I had a history teacher in high school from the Midwest who told us that when her family visited her for the first time in Connecticut they were surprised to see that she lived “in the mountains,” referring to the tall basalt ridges that lead north out of New Haven. Pink lady’s slipper orchids, preferring well-draining soil, grow along their steep slopes in colonies dozens strong in the spring. Vultures float on columns of warm air that radiate off their escarpments.

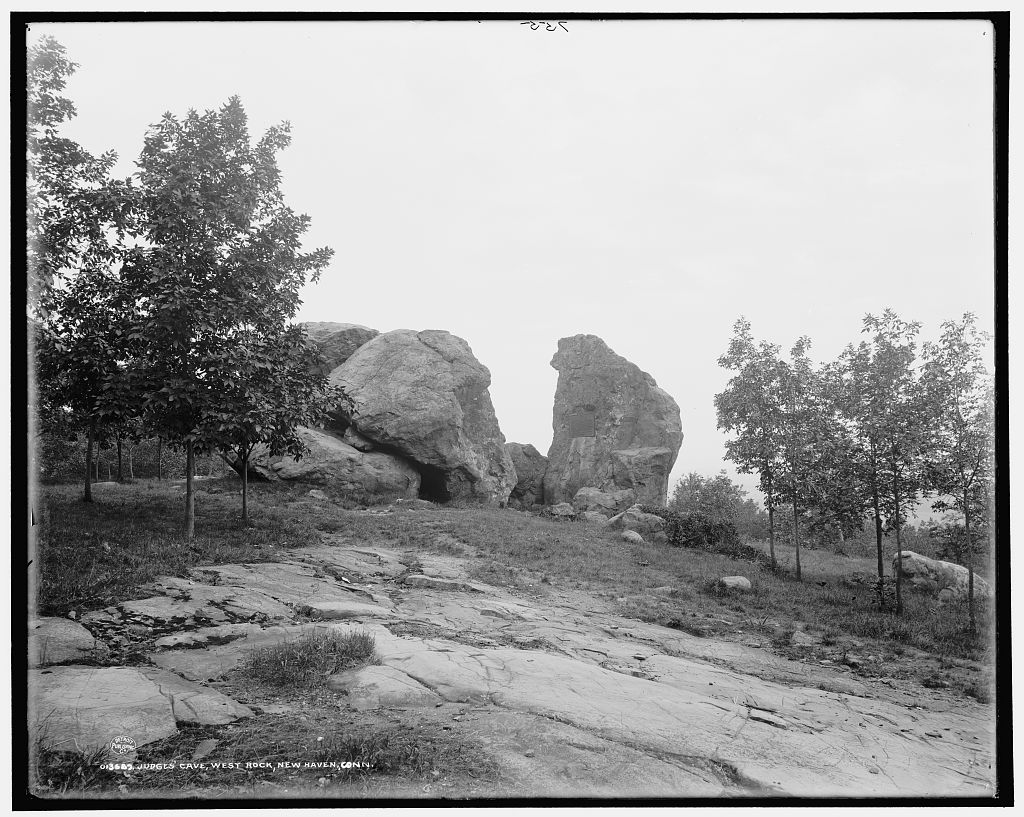

On the way to an overlook on West Rock there’s a fork in the road, with the right fork winding up to Judges Cave, a collection of boulders arranged in a pile. As the sun sets on clear days the light makes the plain brown stone glow red. Screwed into the side of one of them is an orange sheet metal sign:

Here May Fifteenth 1661 and for some weeks thereafter Edward Whalley and his son-in-law William Goffe, members of the Parliament General, officers in the army of the Commonwealth and signers of the death warrant of King Charles First, found shelter and concealment from the officers of the Crown after the Restoration.

The story goes that Whalley and Goffe fled together to the New World and followed fellow regicide John Dixwell to New Haven, where they hid from royal agents hunting them down. Sympathetic locals hurried them between basements and brought them provisions in the woods. Their names now grace three of the city’s main streets that intersect near its heart.

On the sign below the historical context is an unattributed quote: “Opposition to tyrants is obedience to God,” and a date, 1896, denoting the year that the Society of Colonial Wars, a historical interest group whose members claim descent from military and government men active before the Revolution, first installed a bronze plaque on the site. Thieves stole the marker after just a few years. The Society, still active today, did not respond to my inquiries about what might have happened to it.

There’s no record of Whalley, Goffe, or Dixwell ever uttering the quote, but at some point in the early 19th century someone carved it straight into Judges Cave. One text from 1852, Historical Poetical & Pictorial American Scenes by New Haven engraver J. W. Barber, mentions the inscription.1

A few decades later, another New Haven figure, C. A. L. Totten, wrote in a centennial history of the Great Seal of the United States: “One witness, now forty-five, vouches for having scraped the moss out of the letters when a boy, and says his mother, now seventy, knew of it as a child as Regicidal in origin.”2 Despite his efforts to interview New Haven locals, he never found out exactly when it first appeared.

Totten’s interest in the Judges Cave inscription came from the fact that Benjamin Franklin wanted a version of it that swapped “opposition” for “rebellion” to be the Great Seal’s motto instead of E pluribus unum. Totten was a proponent of a movement known as British Israelism, a precursor to today’s Christian nationalist groups. His obsession with the Seal connects him to the contemporary American right and its efforts to spin narratives of divine right and dominance out of the country’s founding.

When Franklin proposed the quote to Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, he tied it to John Bradshaw, chief regicide and President of the High Court of Justice that condemned Charles I to death. Bradshaw died a year before Charles II took the throne, and it’s rumored that before the king could defile Bradshaw’s corpse, one of his sons spirited his remains away to Jamaica and buried his ashes on a hill beneath a cannon inscribed with an epitaph that ended with the line.3

Jefferson later cast doubt on the quote’s origins, noting that he’d only ever seen it in “Dr. Franklin’s hand.”4

It’s possible that it came from Bradshaw’s original tomb in Westminster, which Charles II did destroy on his quest to put heads on spikes next to Oliver Cromwell’s. Like the cannon in Jamaica, no record of that tomb’s design exists. Jefferson liked the quote enough, however, to put it on a personal seal that still marks the gate of a cemetery at Monticello.5

There’s little evidence that Whalley and Goffe actually hid in Judges Cave, but the legend lends a spooky historical credence to New Haven like Salem’s witches or Roanoke’s empty homes: the image of men crouched in a cracked-open rock on top of a hill in a pre-modern dark, wondering what could be happening in the endless woods around them. Two hundred years ago, the story and the quote attached to it helped prop up America’s central myths of freedom and resistance as they were still forming and becoming self-sustaining, even if both might have been fiction.

In Barber’s book, the story of the regicides sits among those of Pocahontas and Washington crossing the Delaware and more obscure early American tales like “The Grave of Lady Fenwick.” Each has an accompanying Spoon River-like poem, and most have a throughline of Christianity vis-a-vis “religious freedom” justifying the American project and the genocide of its indigenous inhabitants.

The final stanza of “The Regicide Judges” adapts the Judges Cave quote further:

Earth shall keep their precept still,

“That to brave the tyrant’s rod,

With a firm unfettered will,

Is obedience to God.”6

In elementary school I took a field trip to the Darling House, a white-painted farmhouse at the base of West Rock on the opposite side of the ridge from Judges Cave. While we crushed apples in a press to make cider we learned that the house had an early version of the lightning rod installed, Thomas Darling being a friend of its inventor Benjamin Franklin.

What would it have been like to be hiding in Judges Cave when lightning struck close by? It’s said that a mountain lion, not British soldiers, once scared Whalley and Goffe from the rocks. Imagine a mountain lion’s shape, lit for a second in a sudden flash of light, in an otherwise dark and empty forest.

- Barber, John W., and Elizabeth G. Barber, “The Regicide Judges,” Historical, Poetical and Pictorial American Scenes: Principally Moral and Religious, Being a Selection of Interesting Incidents in American History: To Which Is Added a Historical Sketch, of Each of the United States, (New Haven: J. W. Barber, 1859), 26. ↩︎

- Totten, Charles A. L., “First Period,” The Seal of History, (New Haven: The Our Race Publishing Company, 1897), 16. ↩︎

- Bridges, Rev. George Wilson, The Annals of Jamaica, (London: John Murray, Albemarle Street, 1828), 2: 445-447 ↩︎

- “Bradshaw’s Epitaph”: a Hoax Attributed to Franklin, 14 December 1775,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0180. ↩︎

- “Personal Seal,”Monticello.org,https://www.monticello.org/research-education/thomas-jefferson-encyclopedia/personal-seal ↩︎

- Barber, 27. ↩︎