about honest lies

Contributor

Discourse

MATTHEW BOHNE (M. Arch II ’17)

During the concluding remarks at the “Aesthetic Activism” symposium, architect and educator David Ruy presented research that exposed a realm of small yet dedicated aesthetic constituencies in the current artistic landscape. These constituencies do not exist in any one space or time, but the media through which they develop and propagate their aesthetics legitimize their reality.

This diversity of geographically displaced, yet aesthetically aligned groups is only possible in a network society, a society post-1981. How can architecture respond to the speed and spread[1] with which knowledge is predominantly generated and exchanged via images on the Internet? As many architectural historians have noted, there is a necessity of a historical-critical distance (approximately 20-30 years) from a period of architectural flourishing to understand it, which is why the 80s are back in most architectural schools. With today’s instantaneous media, that critical distance from a period of time is no longer possible.

What the symposium reiterated is that architecture does not have one single form of mediation. This relationship between the images as the basis for knowledge and the constellation of image-making disciplines present at the symposium recapitulated the necessity to challenge the site of work of architecture and to consider its many mediations.

The recent mid-semester reviews within the school demonstrated that the majority if not all the studios are hyper-contextual. During my own review in Michael Young’s studio, the critics noted that our studio was deeply engaged with context at a time when it’s “uncool.” Needless to say, the context for us was both an aesthetic means and basis to accelerate our speculations.

It is crucial that as architecture students we more intensely engage in the ways in which realities are transmitted, and how our work is mediated and manifested in these realities. It is no longer enough to rely upon orthodox conventions of presentation and representation. Our work is well situated to be explored through film, animation, emerging spatial imaging techniques, and communicated through spam email, social media, and distributed leaflets, all in service of demonstrating and testing its reality, all the while leaving significant space for speculation.

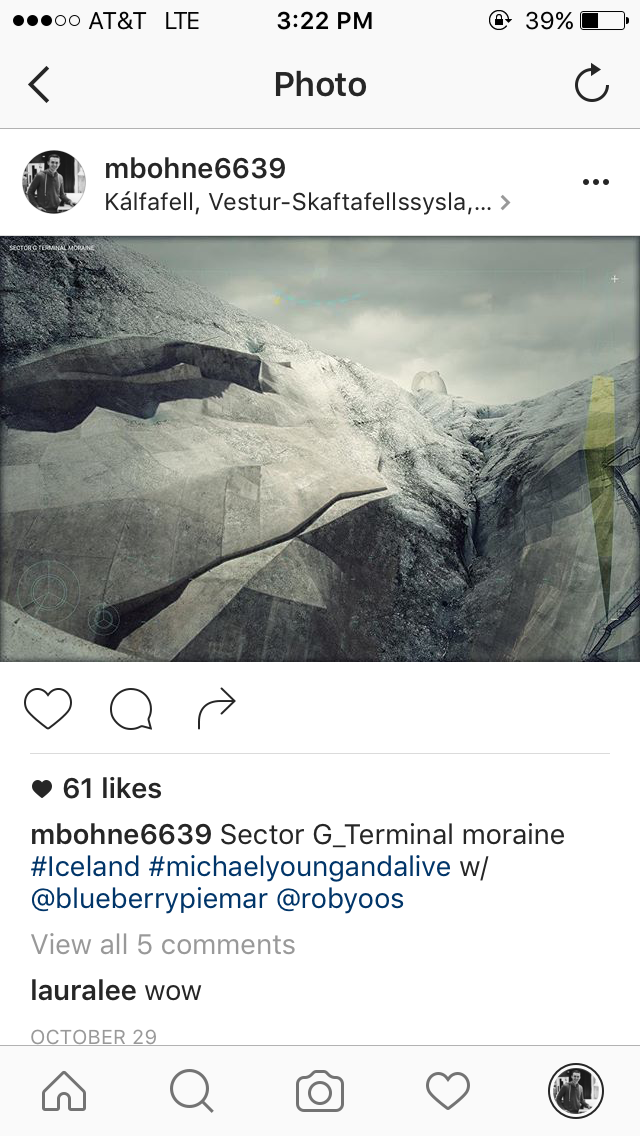

After returning from Iceland during travel week, I chose to post images that my group partners and I had constructed to my Instagram. To my surprise, assigning them a location and using familiar hashtags from my travel pictures was enough to legitimize these images as real. They were consumed by my friends online, who called them “amazing” and found themselves questioning, “is this real?!” Of course, this is just one simple example. These mediations give new agency to the architect, a means with which to introduce and test an imagined future: the architect’s version of reality.

Our instantaneous access to visual information in its many forms is a challenge to all of us. How does the future we envision begin to fit within an interconnected global network? It has to look real. And in defining it, we have to consider the mediations that allow us to build our own constituencies, or as David Ruy stated, “10,000 small political parties.”

I owe a lot of the development of these ideas to conversations with Michael Young, Sam Jacob, Sean Griffiths, Jennifer Leung, and Mark Foster Gage. I am grateful for their provocations.

- An idea introduced by Hito Steyerl in “In Defense of the Poor Image”

- See “Make-Believe: Parafiction and Plausibility” by Carrie Lambert-Beatty. Published in OCTOBER 129, Summer 2009. Pp. 51-84. MIT Press.