Ample Spheres of Yew: Topiary as Guide and Co-existent

Contributor

Co-

Nocturnal Medicine is the collaborative practice of Michelle Shofet and Larissa Belcic. They are based in New York City.

Western ideology has long upheld a binary designed to keep the powerful and well-provided-for safe, fed and pleasured: on the one side, humans, and on the other, everything else. This “everything else” largely consists of resources to be exploited for economic and material gain, and of “nature”–a world of landscapes and creatures untouched by the human hand, a source of pleasure, comfort, and retreat. Both of these are distancing concepts, predicated on an ontology of separation and hierarchy between humans and our companions in Earthly existence. These ideas are implicated in the twin forces of colonialism and capitalism, wielded by them as tools that justify and enable exploitation. Conceptions of the nonhuman as resource grants permission for wealth-building via extraction and control, while ideas of “nature” insulate us from the destructive consequences of these actions, reassuring us with a vision of a world “out there,” pristine and untouched.

As we settle into an epoch defined by the unraveling influence of the human hand, it becomes harder and harder to hold on to these distancing conceptions of the nonhuman. Today, images of “nature” grievously tarnished by human influence confront us constantly. Where there were once perceived divisions between zones of domination and reserves of pristine “nature,” there seems now to be only an inescapable ooze of interconnectivity. Each action we take implicates us further and further in a web of painful horrors–extinctions, wildfires, bird bellies full of plastic. Stuck in that web are we humans, increasingly inextricable from our surroundings, so much so that the word “surroundings” loses its meaning. As dreams of “nature” fall away, so too do ideas of “natural.”

In their place bubbles up a materially promiscuous bisque wherein human influence, the organic and the synthetic entangle endlessly into strange new ecosystems, weathers, creatures, soils. Moving forward from this moment necessitates the practice–individually and societally–of being with the feelings that emerge as we become acquainted with the freak landscapes and systems of our making, and of embracing these entities as the realities that populate this strange new world. There is, after all, no turning back.

So much of contemporary landscape architecture deals with the project of remediating, naturalizing or covering up the impacts of the built environment. The dominant aesthetic paradigm represented in this work is rooted in the visual replication of a “nature’” undisrupted by the human hand. Ironically, these landscapes are often constructed atop layers of geofabrics, planted in engineered soils bejeweled with hydrogels, and fed through snaking polyethylene irrigation systems. What happens under the ground is, in many ways, more honest about the pervasive, messy bisque of entanglements that characterize our day than the curated image above it. The practice of tucking away the underbelly and centering on the perfectly curated image of “nature” at grade is not helping us tap into the reality of our current moment. Practices that camouflage the inherent constructedness of the landscape blind us to the complex, interconnected mesh of systems and agents that make up our world–a web we must actively learn to attune to.

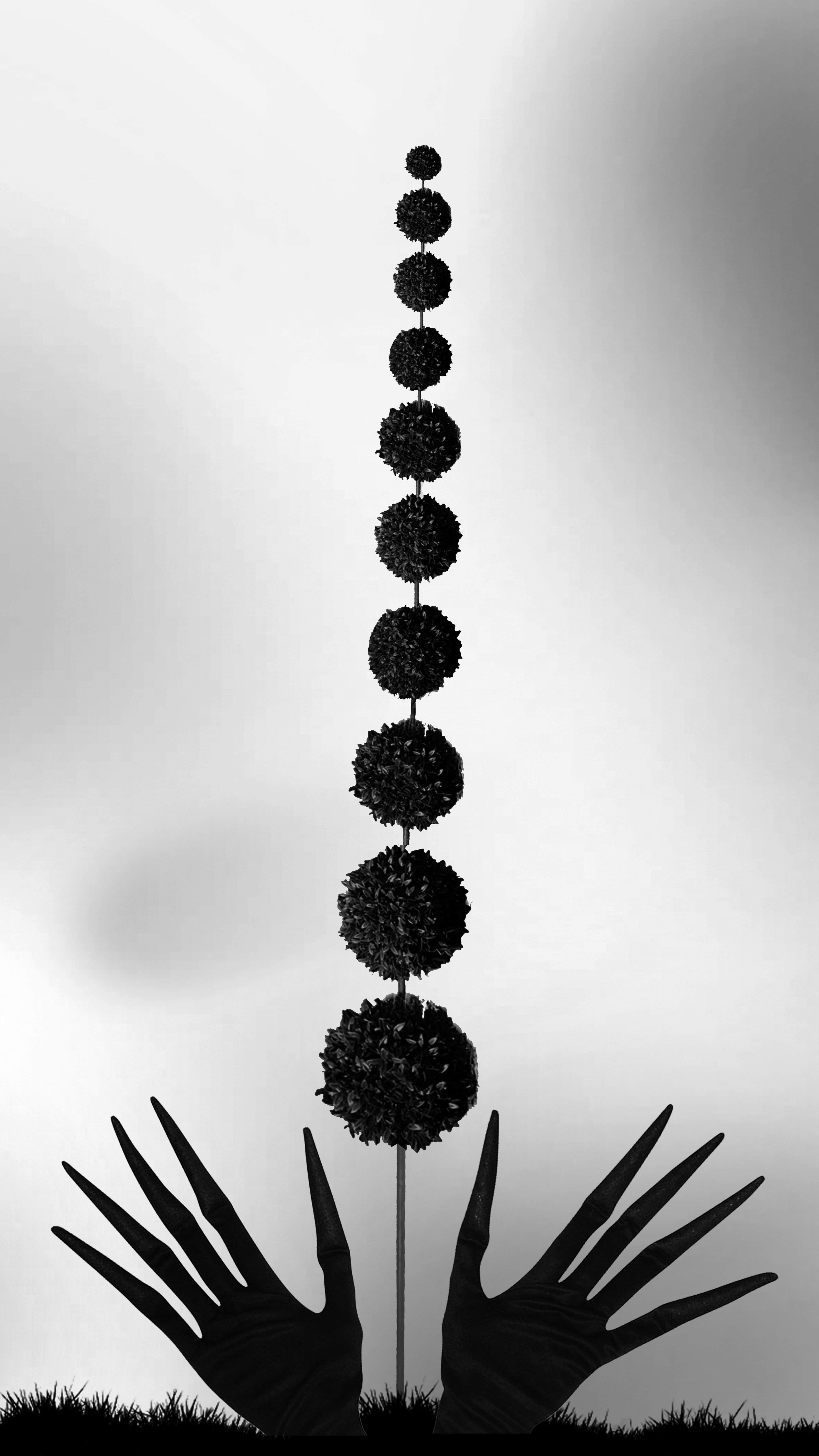

Instead, in this essay we champion the use of alternative aesthetic paradigms within the landscape arts that can guide us in the task of awakening to and living with the material promiscuity that marks this new era. One such paradigm already holds potential to fill this role, though today it is mostly relegated to historical gardens, the front yards of those wishing to emulate the sophistication it once stood for, or, enshrined in polymers, the home decorating aisles of chain department stores. We speak, of course, of topiary.

With lineages in the garden traditions of multiple cultures, the art of topiary is the long-duration shaping of perennial plants into forms that are in clear aesthetic contrast to the plants’ innate growth patterns. In the European tradition, topiaries have served as expressions of human dominance over plant-life—baroque displays of our ability to contort wild, living systems into domesticated, Euclidean pleasures. The topiary’s documented history as an art form stretches at least two thousand years, and throughout, it has retained its role as a site for the blurring of distinctions between “natural” and “artificial.” The very act of conforming a plant’s intrinsic desires to those desired by humans celebrates the mutant synthesis of organic life and exuberant artifice, hinting at the fallibility of those categories. Further complicating these distinctions, contemporary topiaries can be equally plants or plant-simulating plastics.

While it is true that traditional topiary is rooted in practices of domination, its embrace of material promiscuity reveals great potential for a reinvigoration of this art form as an ornamental gardening practice for the current age. Topiary offers us an entry point into a space where binaries of plant/human, natural/artificial, synthetic/organic can blur. We propose topiary as a queer-affirming space that heartily embraces the disillusion of these binaries. It does not attempt to resolve the categories it more firmly belongs to, and in fact maintains its ambiguity as a point of celebration and power. As an art form and practice that occurs between humans and plants, the topiary is ripe with potential to bring us into a place of a deeper relationship with plants, with the nonhuman, and with ourselves as ecological creatures.

In order to tap into its potency, though, we must redefine our cultural relationship to topiary from one of domination to one of intimacy and co-creation. This means that rather than denoting a prescribed outcome of the plant’s form, allowing for a dialogue to unravel between plant and sculptor; making space for imperfection and uncertainty instead of sticking to a script; inviting a dynamic of mutual pushing and pulling; embracing an expanded material spectrum beyond plant matter and plastics.

If we let it, the topiary can be a guide in growing comfortable in this new era. By teaching us to celebrate ambiguity, it strengthens our ability as humans to relinquish resolution in favor of the joy of the in-between. Both through the process of creating topiary and in the act of walking amongst them, we reconstitute our relationship to “nature” and invite new creatures to populate our landscapes and cultural imagination.

Imagine this: you are picnicking on a blanket in a park. The land surrounding you is dotted with mutant topiary forms–towering, green obelisks with rogue branches emerging from smooth, shaved planes. Lying at the foot of one of their bodies, you reach your hand to caress the ample spheres of yew at its base. Your eyes find that they soon give way to smaller spheres of moss-encrusted polymeric foams. Your gaze and the creature both reach evenly towards our new strange sky.