Ten Years

Contributor

10 • Reflections

I was 20 years old when I was assigned my first desk in Rudolph Hall. I was a sophomore in Yale College when I first felt the heat of Zap-a-Gap curing on my fingertips, when the scent of freshly laser-cut chipboard and the musk of still-wet Rockite imprinted themselves in my brain, when the first specks of basswood dust found permanent lodging in my lungs. Last week, I turned 30.

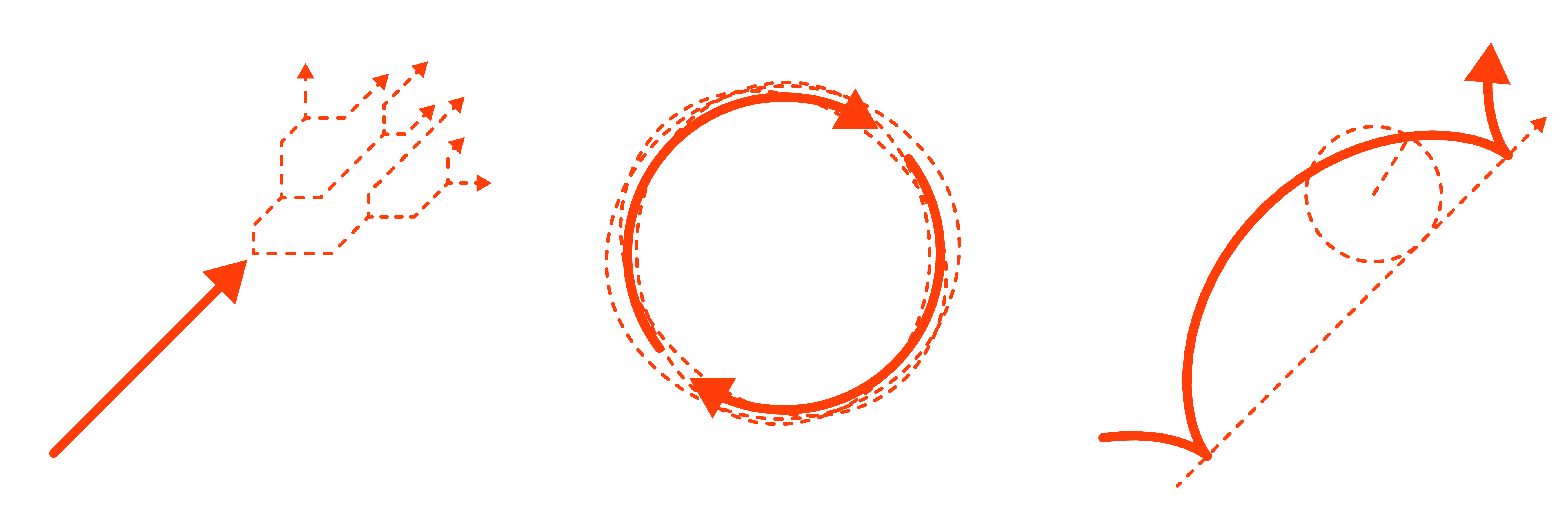

The forward march of time is an unstoppable pruning of the branches of possibility. Before us are spread infinite tendrils of what could be, behind us only the single straight line of what was, the present moment borne ceaselessly forward like the carriage of a cosmic zipper. But the straight line of history is a brittle geometry. Einmal ist keinmal—what happens but once might as well not have happened at all.1

In 2014, my first architecture course was called The Analytic Model, taught by Emmanuel Petit with Kyle Dugdale—then a PhD student—and two M.Arch teaching fellows. That course has since been replaced in the curriculum by Scales of Design, for which I am currently a teaching fellow myself. I find myself in the same familiar play, cast as a different character, retracing my steps in new shoes. My own younger existence presents itself to me now as a residue in the building, cast into the concrete and woven into the carpet, a ghost image bit by bit continually overwritten. In the decade in between, I fell asleep on paprika carpet and started drinking coffee. I had a job in architecture, a few jobs outside of architecture, and many jobs that straddled the line. I fell in love and felt my heart broken. I tried and failed at doing all kinds of things and being all kinds of people. I often remarked that in my various forays building things, making art, designing with friends, and working for developers that I had been orbiting architecture.

Orbiting is an eternal process of falling. Though the pull of the center rules our movement, we are locked in constant radial distance, never getting closer or farther away. A circle is inescapable. Round and round, we wear a track into the ground, making the form of our patterns realer and realer, each revolution taking us back to where we started. Eternal return is the heaviest of burdens.2

As it was ten years ago, Moon assigns a pasta truss. Rubin crusades for New Haven. Newton worries about our fingers. Deflumeri is the most important person in the building. None of these men seem to have aged a day. Nothing has changed, but so has everything. Pelkonen is as beloved as ever but the canon she teaches has never been under greater scrutiny. Ten years ago, Bob Stern was dean, a figure as imposing as he was diminutive, ever armored in a tailored suit, pocket square, and lightly perched glasses that barely shielded us from his withering gaze. Students received less financial aid than they do now, and Local 33 was just an occasional story in the Yale Daily News, a long way away from recognition by the NLRB. The Architecture Lobby had just been founded the previous year by now-emerita professor Peggy Deamer, while Paprika was still months away from being launched by a group of second-years.

The revolutions of the earth are cyclical movements. Relative to the sun, the earth returns to its starting point every year. But the center cannot hold. The sun also tracks a galactic orbit, so in fact the earth never really returns, instead making a cycloid curve. We cannot return, we can only look behind from where we came, and go round and round and round.3 Even the galaxy is in motion—we are cycloids within cycloids in a fractal universe. The difference between circularity and linearity, it turns out, is only a question of scale.