Women Architects of Modern India: Their Long Search for Identity

Contributor

Ca(non)

Madhavi Desai [1] is an adjunct faculty member at the Faculty of Architecture, CEPT (Center for Environmental Planning and Technology) University, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. She is the author of Traditional Architecture: House Form of the Islamic Community of the Bohras in Gujarat, 2008; co-author of Architecture and Independence: The Search for Identity, India 1880 to 1980, (1997); The Bungalow in Twentieth-Century India: The Cultural Expression of Changing; Ways of Life and Aspirations in the Domestic Architecture of Colonial and Post-colonial Society, 2012; and Architectural Heritage of Gujarat: Interpretation, Appreciation, Values (2012); and editor of Women and the Built Environment in India, 2007.

Over the past couple of decades, there has been a growing interest in South Asian architecture in the context of modernist history and theory, especially as the concept of the ‘other,’ ‘hybrid,’ or ‘alternate’ modernisms took root. Modernism’s homogeneity and universality as it developed in different geographic locations, time periods, and cultures has been increasingly questioned. There is also an increasing awareness that the assumed linearity, autonomy, and master narrative of canonical modernism needs to be challenged.[2] The narrative of Indian modernism has to be viewed from this perspective.

Even as global interest in South Asian architecture increases in the context of mainstream modernist history and theory, scholars and practitioners in India continue to ignore the role and contribution of women in the discipline. From a historical viewpoint, it can be said that the long struggle for freedom from British imperial rule not only affected the stylistic characteristics of Indian architecture, but also brought about far reaching educational, social, and political changes in Indian society at large. The roots of the women’s movement lie in the social reforms[3] of the nineteenth century, during the British Raj, which came about mainly as a result of the colonial encounter. The spread of modern education led to higher degrees of liberty and equality within Indian society. As time passed and new employment opportunities emerged the spread of modern education created a dichotomy between the home and the outer world amongst middle class men. They, therefore, attempted to change the traditional family and the domestic confines of women without disturbing the core patriarchal norms determining the role and status of Indian women.[4]

The twentieth century brought further changes. The nationalist struggle for independence under the leadership of Gandhi gave rise to a great interconnectedness between political and social issues. Indian women came out of their homes and into the public realm in large numbers, inspired by Gandhi’s political call and philosophy.[5] The women’s movement created an avenue for women to progress in many fields. Its impact was also seen in the context of architecture as the profession began to develop and girls increasingly opted for it.

It is at this time that a small number of women began to take hesitant steps in the up-and-coming field of architecture. In the 1940s, a few pioneers from elite families broke male bastions to go beyond the traditional confines of the era. From there onwards, the careers of women architects nearly parallel the development of architectural modernism in colonial and postcolonial India. It was a struggle for the increasing number of middle class women who joined in the late 1960s to early 1970s. They had to deal with severe social restrictions, the absence of any networking, and a lack of professional understanding or gender awareness among parents and Indian society. At the same time, they were the beneficiaries of political reform and the project of modernity in the twentieth century.[6] Within the larger framework of modernity, each architect followed a personal vision of architecture—achieving professional success through perseverance and tenacity.

In the twenty-first century, a lot has changed. In the past three decades there has been a sharp increase in the number of women joining architectural degree courses. There are about 500 institutions in India that teach architecture where 40 percent to 60 percent of the student body admitted each year are women. However, only about 15 percent to 17 percent eventually become active in the field, and this is a challenge for the profession to address.[7] Graduates who attempt architectural practice typically veer off towards interior design, where there is a critical mass of women practitioners. Because it is very hard for women to succeed in private practice, the rate of attrition is high in the field. Some take up conservation or landscape, others join non-governmental organizations, while still others find careers in teaching, research, or writing. Some of those who do not drop out of the field altogether move towards fashion, graphic design, furniture-making, film-making, or other related design disciplines.[8]

In spite of that, there is a tremendous breadth of accomplishments as well as a heterogeneity of design approaches and attitudes exhibited by women practitioners today. Their collective work and personalities make them much-needed role models and mentors, as there are very limited numbers of single woman-headed organizations. Joint husband and wife practices are increasingly popular and successful. However, it is important to note that a majority of Indian architects do not call themselves feminists; they reject the label “woman architect” and believe that the women’s movement in India has not had much influence on their lives and careers.[9]

These women have now created a substantial body of work and developed an identity in the national context. The architects’ style and aesthetics range from the purely modernist to those with elements of postmodernism, regionalism, and, more rarely, deconstructionism. It is obvious that a singular search for an Indian identity does not exist; it is rather fragmented and takes several directions through cultural transfers and localization. A few larger practices are affected by global aesthetics and images.

A majority of Indian women are connected with architectural education in myriad ways in spite of their busy practices. The academic connection gives them opportunities to develop a different set of skills and to share their personal expertise with younger generations. Their self-assured work expresses maturity and confidence; rather than directly copying western solutions, they struggle to arrive at an Indian consciousness of design as they move in transnational contexts in an increasingly globalizing India. It is time we acknowledge the contributions of Indian women in architecture and the hurdles they face.

The first generation of (very few) women in architecture were exceptional and paved a path for the generations to follow. They belonged to elite families such as Gira Sarabhai and Pravina Mehta, and were socially well-connected. They joined the professional course due to their families’ liberal views and unconditional encouragement for professional education. The next generation of women, in much larger numbers, took hesitant steps in the profession without mentors and network support. They negotiated several forces of resistance, sometimes with non-conventional approaches and attitudes. They generally have a strong character, an assertive nature, a high commitment and a thoroughly professional attitude towards their goals. For example, Brinda Somaya, Revathi Kamath, Shimul Jhaveri and others are trail-blazers who pursued various directions while setting new trends to create identities for themselves. A definite paradigm shift is observed as the Indian society begins to rediscover its roots in the 21st century. There are social and professional conditions that are beneficial to women. There are newer prospects and opportunities in the field of architecture today. It is time to rethink conventional approaches and established paradigms to go beyond male/female duality in dealing with history, theory, practice, and education to meet the challenges of the 21st century. We need to have a supportive professional community, to develop an alternative model that combines professional and family life and to create more opportunities for women to embrace non-traditional modes of practice.

Photo 1: An activist during the freedom struggle, Photo courtesy: Mr. Priyavadan Randeria.

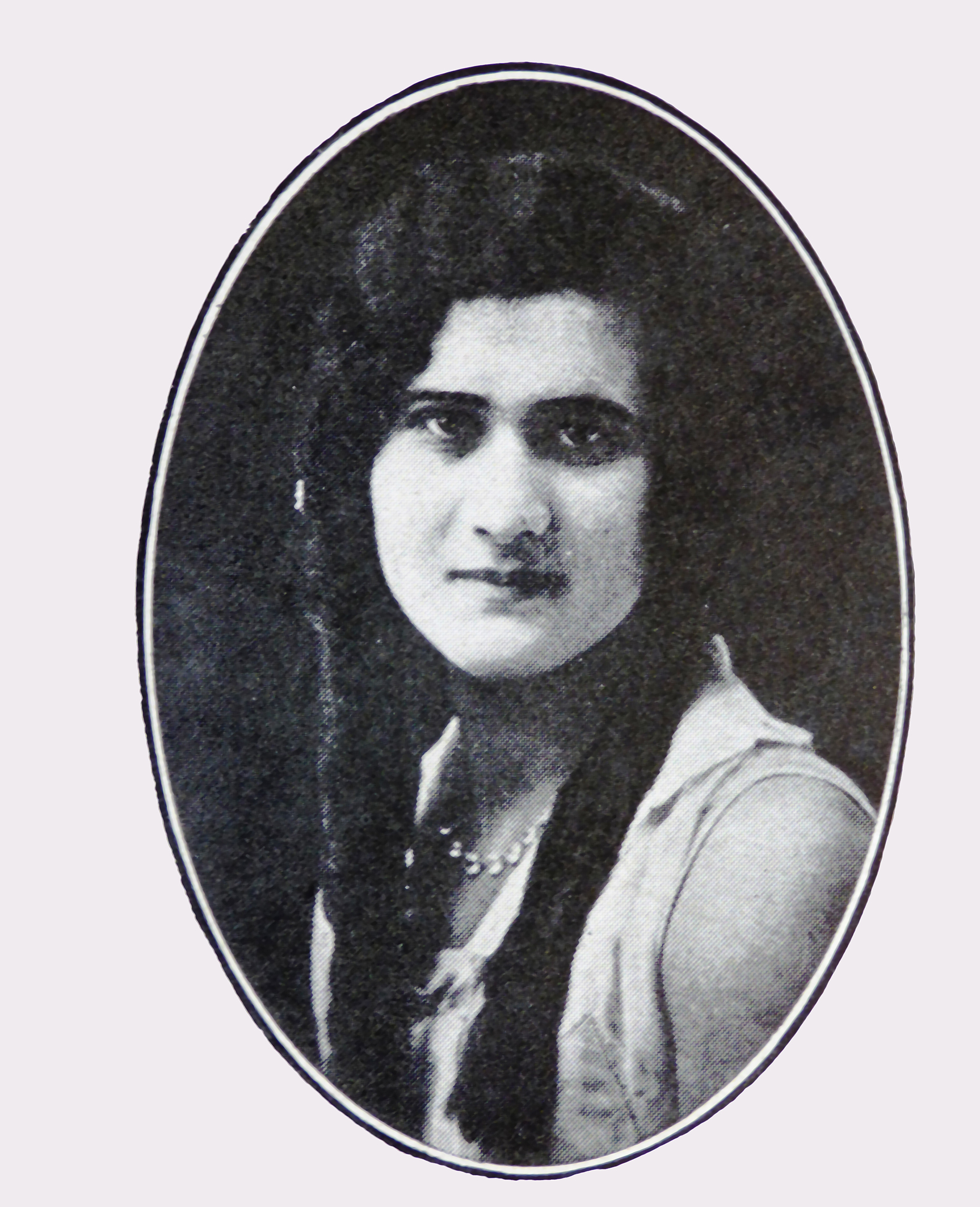

Photo 2: Perin Mistri is believed to be the first woman in India to be professionally qualified in Architecture. Photo courtesy: Parsi Lustre on Indian Soil

- The article is based on the author’s book Women Architects and Modernism in India, Narratives and Contemporary Practices, London and New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Chatterjee, Partha. A Possible India: Essays in Political Criticism. Delhi, New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- These include the abolition of Sati tradition, encouragement of widow remarriage, discouragement of polygamy and child marriages and other reform efforts.

- Desai, Neera. Feminism as Experience: Thoughts and Narratives. Mumbai: Sparrow, 2006.

- Thakkar, Usha. “Vimla Bahuguna and the Legacy of Gandhian Politics,” in Culture and the Making of Identity in Contemporary India, edited by K. Ganesh and U. Thakkar. New Delhi: Sage Publications, 2005.

- Lang, Jon, Madhavi Desai, and Miki Desai. Architecture and Independence: The Search for Identity-India 1880 to 1980. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Desai, Madhavi. Women Architects and Modernism in India, Narratives and Contemporary Practices. Abingdon, New York: Routledge, 2017.

- Desai, Madhavi. “Architectural Education in India: Women Students, Culture and Pedagogy.”Matter, 2015.

- Throughout the interviews that I conducted for the book (and in the earlier questionnaires), I found that a majority of the women I spoke to rejected the idea of their being feminist or having had any impact of the women’s movement on their successful careers. These were exceptions, but very few.