Night soil, amethyst domes, and a meditation house: Architecture as pictured in the The Paul Kagan Utopian Communities Collection at the Beinecke Library

Contributor

Ends of Architecture

In 1975, after five years of research, historian, TV writer, art director, graphic artist, and photographer Paul Kagan published New World Utopias: A Photographic History of the Search for Community. The book is a visual survey of communities in California, from roughly 1870 to 1970. The Beinecke Library now holds Kagan’s research materials, from letters, documents, and notes, to photographs taken by Kagan on his visits to the communities, or former sites thereof.

1

2

3

Lama Foundation

In the preface to New World Utopias, Kagan explains that staying at a “present-day New Mexico commune” initiated his research. This was the Lama Foundation, the still-extant spiritual center near Taos, which described itself as a “center for basic studies,” not beholden to any “single way or doctrine.” Among the materials in Box 30 is an oversize brochure advertising the foundation’s summer course in “basic studies” and featuring many of Kagan’s photos.

The brochure includes a large image [1] of the main building—the “residential building”—with requisite adobe walls, domed roof, and octagonal window, built by people who went there to study. At Lama, work was synonymous with study: the summer course involved helping with the construction of “one underground solar greenhouse; barn; chickenhouse; seven A-frame summer cabins; two skins for existing domes; five thousand adobes for new buildings; a children’s house and a meditation house (to be built atop 9,400 foot knoll in silence without power tools).” [2]

Llano del Rio and New Llano

Llano del Rio was a communist settlement in the Mojave Desert established in 1914 and deserted in 1917, when its residents relocated to New Llano in western Louisiana. Kagan’s images show the ruins of the town including a desolate picture of a dry fountain (one reason the comrades left Llano del Rio was the lack of water).

But pictures Kagan collected from former residents show buildings in operation. They are two-story wood framed; traditional and sturdy [3]. Alternative life at Llano meant May Day parties, children who worked, and universal basic income, not unconventional architecture. That said, there were architects involved, including the legendary feminist Alice C. Austin, who is pictured standing in the half-finished men’s dormitory before a model of what’s described as an “ideal city.”[4]

4

5

6

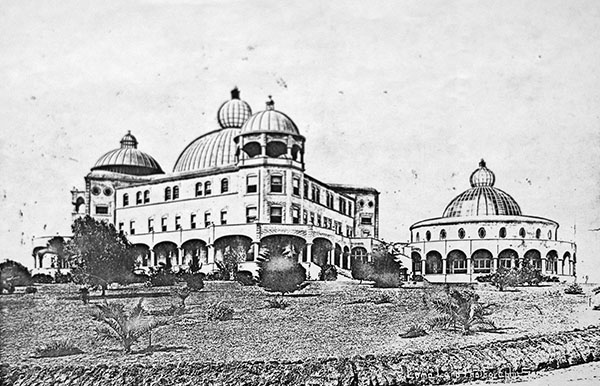

Point Loma a.k.a. Lomaland is located north of San Diego, looking out to sea over the Sunset Cliffs. Founded in 1897 by Katharine Tingley (known to some as “Purple Mother”), it housed the headquarters of the American branch of the Theosophical Society (Theosophy is an occult religion developed in the nineteenth century; its tenets include karma, reincarnation, the “secret brotherhood” of ancient spiritual masters known as Mahatmas).

This place was fancy. It had Venetian-style ornamented buildings with glass domes—one covered with amethyst [5], lovely gardens with flowers and avocado trees, sweeping lawns for yoga, and even a Greek amphitheater and portico looking out over the ocean where female residents staged elaborate performances of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Five hundred people lived there at its peak, building the buildings in exchange for room and board. The site was sold to a developer in 1942 and the buildings were torn down. The first Greek amphitheater in America, as its plaque reads, is now on the campus of Point Loma Nazarene University.

7

8

9

Tassajara Zen Mountain Center

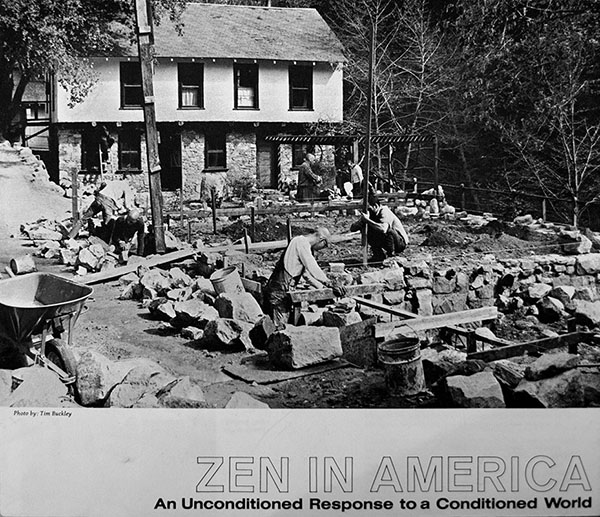

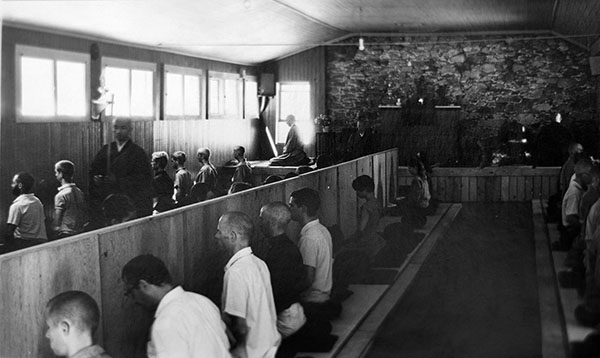

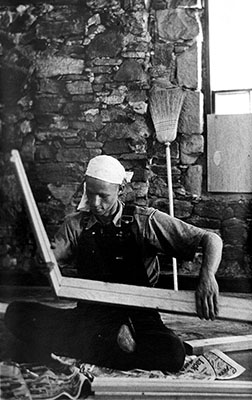

Basically the opposite of Lomaland, but located in an equally magnificent setting, is the Tassajara Zen Center. Perched high in the Santa Lucia Hot Springs north of Monterey, on the site of the Tassajara Hot Springs, the Zen Center inhabited practical but well-constructed buildings made of wood and stone [6], with minimal wood-paneled interiors, carrels for meditation [7], and stepped gardens for growing food. In the photos, we see a man in a headwrap and no shoes joining two pieces of wood [8]. There are two men digging (or maybe setting) large stones.

What does “withdrawal from everyday life” mean architecturally? In part, it implies a devotion to daily practice, including construction projects. As a promotional brochure read: “following the way of the famous Zen Master who said, ‘a day of no work is a day of no eating,’ working is an intrinsic part of the practice—integrating meditation and everyday life.”

Farallones Institute

From what I read in the collection, the Farallones Institute was a commune devoted to historic preservation, night soil, and photography. The institute started with a group of people led by Helga and Bill Olkowski who bought a condemned 1890 Victorian House [9] in Northwest Berkeley, and started the experimental residence known as the “Integral Urban House.” In their own words, the residence was “an alliance of architects, agriculturalists, biologists, engineers, and artisans working together to design integrated, small-scale, self-sustaining systems of habitat and life support.” In this case the architecture was not the shelter or symbol of utopia, but the raison d’etre: house itself as an ecological system.