Four Cautionary Tales of Prison Architecture

Contributor

Fiction

GUS STEYER (M.ARCH I, ’19)

First Prison

Second Life Facility

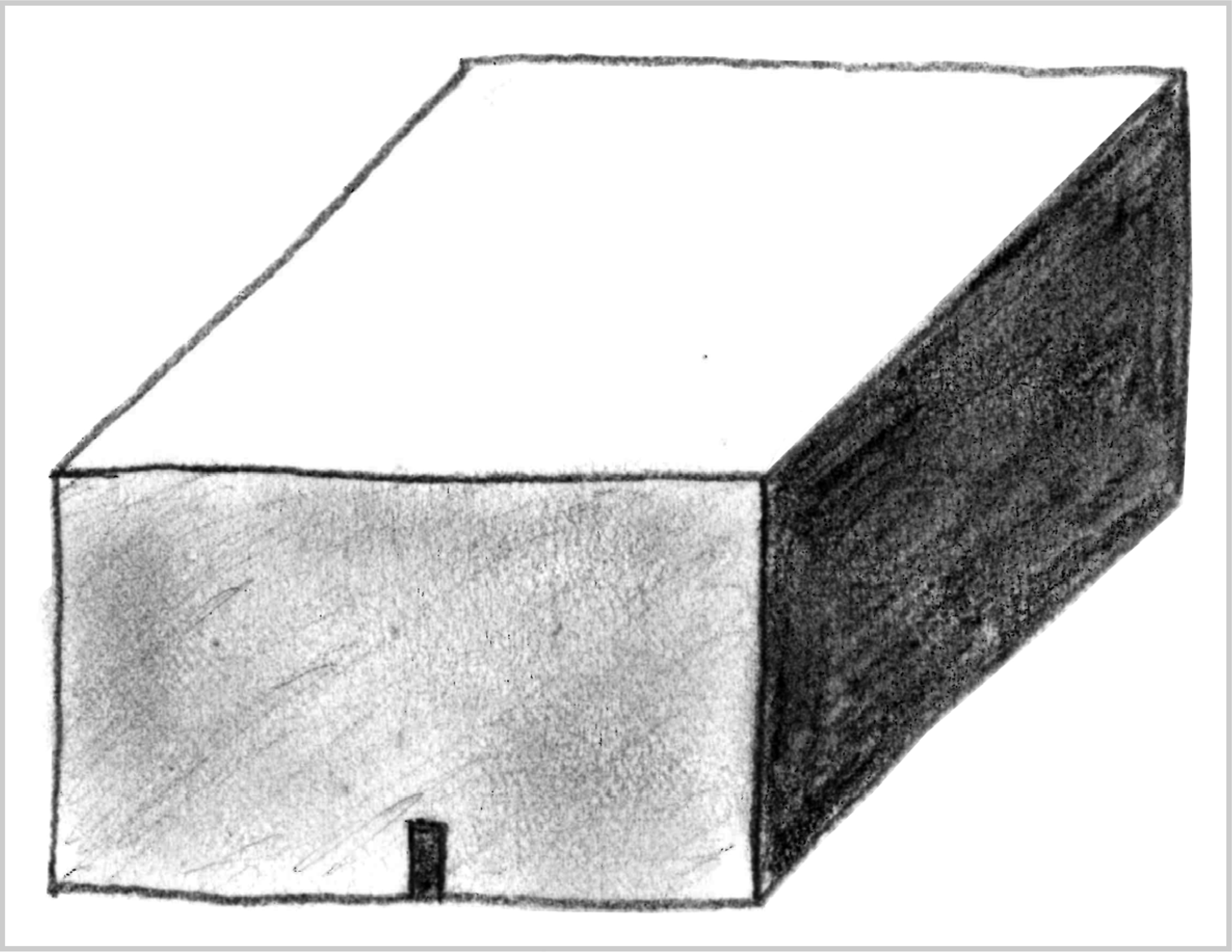

The prison is a simple box full of ergonomic chairs that carry inmates in hospital gowns. There is enough space in this box for each inmate to be moved around in an exercise routine and for the staff to circulate safely. The staff install the residents into their chairs, refill their feeding tubes, and ensure that each chair is working properly. The purpose of the building is merely to keep the residents alive, for they will not spend another waking moment in the real world.

After their conviction, each of the residents was deemed permanently unfit for society and sentenced to “identity upload.” Each resident’s identity was uploaded to a digital world rated by the American Justice Department as equivalent in every way to the world that we inhabit. Human rights advocates failed to establish any measurable shortcomings of this digital alternative reality. In this new realm, the residents are able to live out their lives in the manner they choose while “law‐abiding” citizens in the real world carry on safely without the most dangerous members of society.

Second Prison

Family Facility

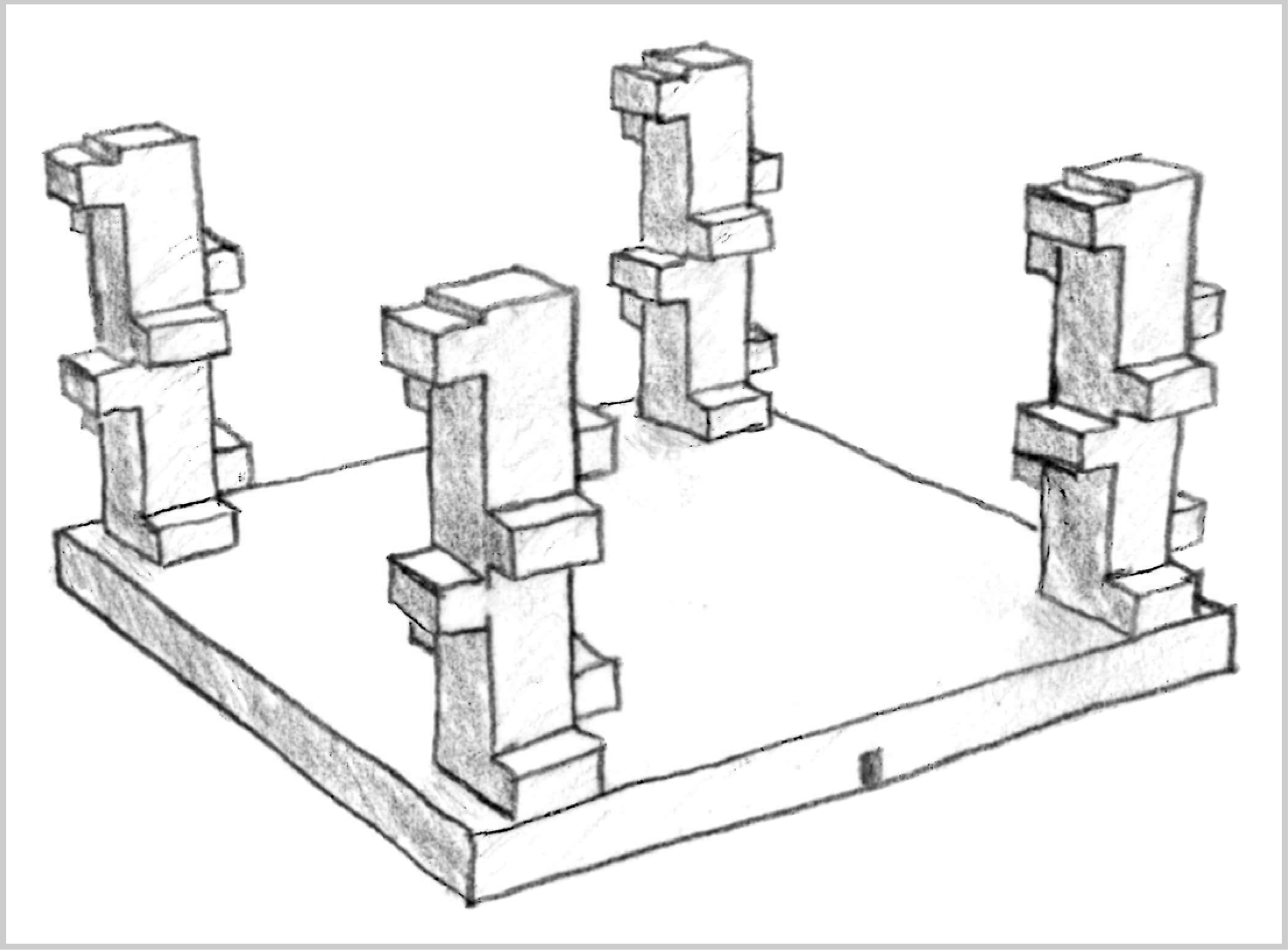

After decades of Evaluation Studies, the preeminent experts in sociology and psychology agree that a “family” social structure is optimal for mental health and critical to the development of normal social habits in individuals exhibiting antisocial behavior. The prison boards have responded accordingly.

Upon arrival, residents are placed into “families” of four to six members varying in prison experience, sentence, and other characteristics. As the residents advance through their sentences, they progress from “child”—in this role they are shown the ropes by an older resident—to “parent”—they show another resident the ropes—to “elder”—where they take on larger, group responsibilities.

Though the prison staff only intervene to prevent physical altercations, they meticulously document the residents’ performance in each of these roles. Through documentation, the staff decide when and if a resident may advance to the next role, or if they must be demoted due to poor performance.

The architecture of the facility reflects this social structure. Each family has its own tower in which the sleeping chambers are collected around a spiral staircase. At the base of each tower, the family has a small social area. These towers are collected around large dining halls, each of which serve between 15 and 20 families.

Third Prison

You Choose Facility

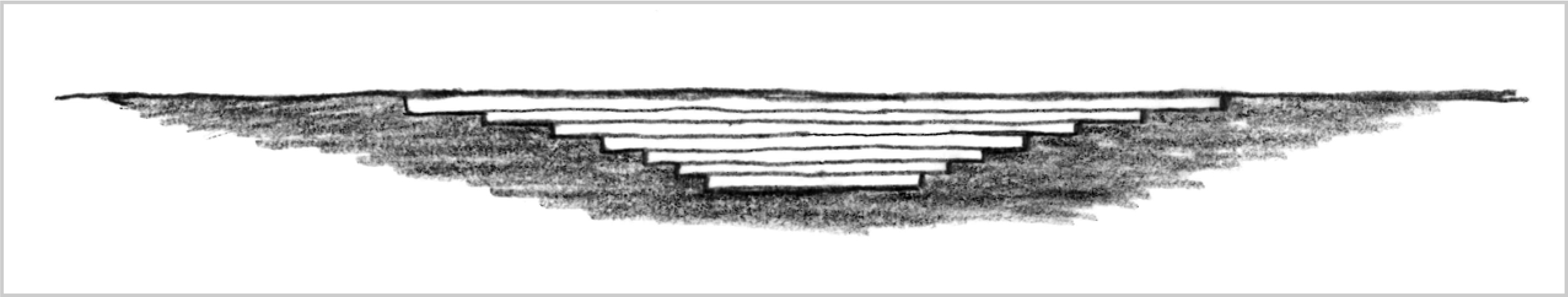

The facility is a vast, stepped pyramid funneling into the ground. The total built area of the facility is calculated to accommodate the maximum potential criminal population. The roof of each layer is fitted with a digitally rendered image of the sky, so as to imitate the world above.

Criminals are sorted into each layer based on their own preferences. Upon conviction, individuals are administered the Societal Acceptability Test. The test asks each future resident what he or she considers “acceptable” in society as well as how they would discourage “unacceptable” behavior. Based on their results, they are transported to a layer within the facility where all the inhabitants share their determinations of what is “acceptable”. Each group forms an autonomous society with its own laws and set of moral codes. Each layer must somehow generate economic output, but they may do so however they wish, as long as it fits the agreed-upon rules of their society. If a resident later shows that he or she is not suited to his or her new society—the staff monitors the goings on in the prison with a variety of technological equipment—the resident undergoes the test a second time and is relocated according to his or her new results.

Fourth Prison

Chip Facility

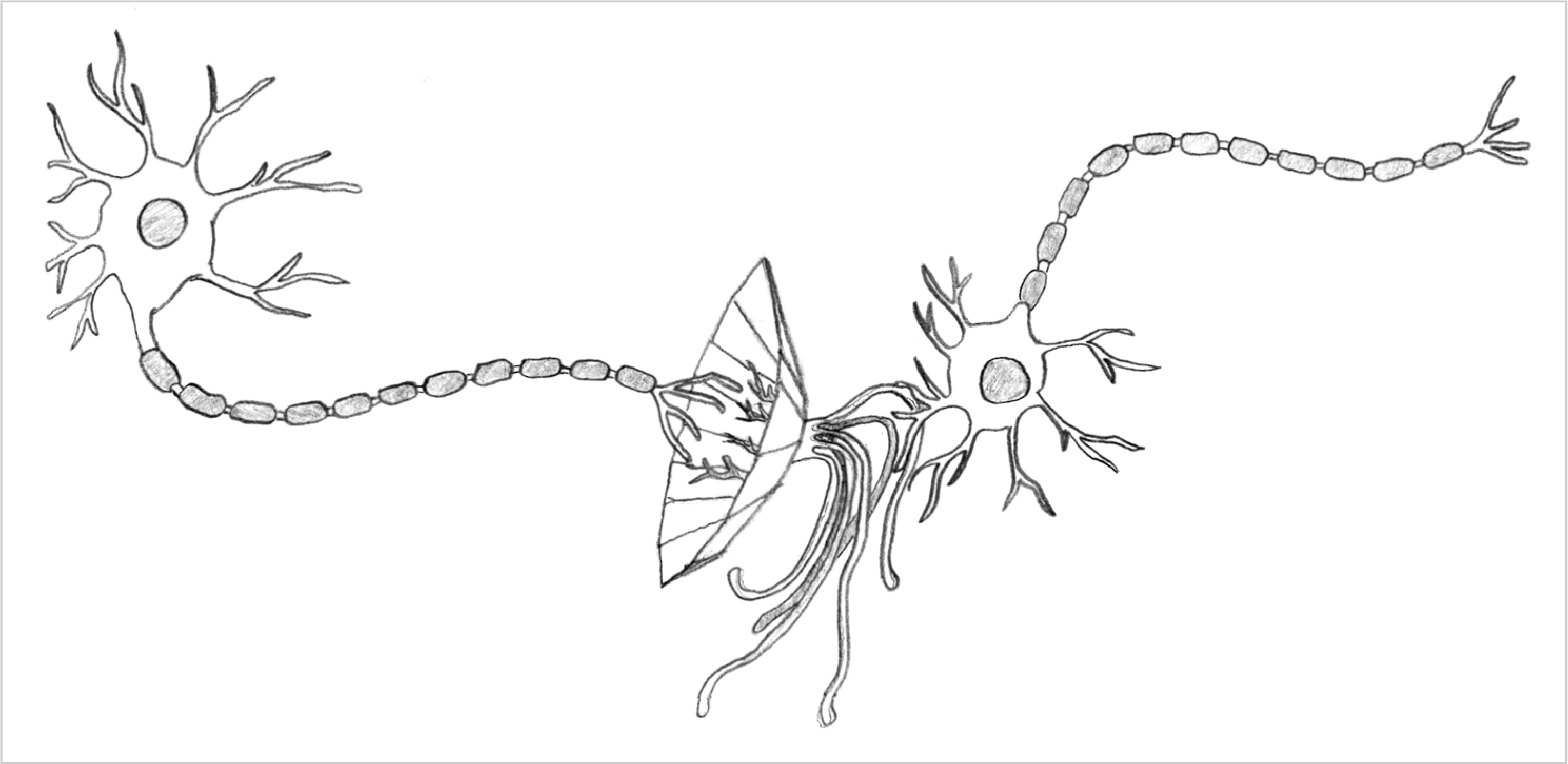

Upon conviction, individuals can forego a prison sentence and opt for a “Behavioral Modification Installation.” In this facility, the judge must first determine what infractions each criminal is predisposed to commit. The criminal is then implanted with a chip. The implant lies dormant until it recognizes the neural pattern associated with the actions it was programmed to prevent; in this case, it will send a neural block that prevents the criminally associated synapses from firing. The individual will find him or herself unable to commit the crime. Over time, as that neural circuit goes unused, the pathway will weaken and the individual will become naturally uninterested in his or her predisposed illegal actions.

This prison does not rely on a facility. Spatial variables only come into play when an individual’s vices consist of some form of trespassing. In this case, the implant may begin to restrict his or her comings and goings on private land and thereby define a new, restricted world.